The College Graduation Rate Flaw That No One's Talking About

Blog Post

Shutterstock

Oct. 9, 2014

Any discussion of federal graduation rates for colleges will immediately spark a laundry list of concerns about their validity. The most common of these critiques is that their inclusion of only full-time students attending college for the first time excludes large numbers of transfer and part-time students that may well also be earning credentials.

What’s odd is that these discussions never turn to a larger structural flaw, one that gives rise to talking points of questionable veracity and makes comparable looks at graduation rates nearly impossible for more than 2,300 institutions of higher education. And even though many of the other problems with graduation rates are being addressed by additional federal data collections, there’s no indication that this one will be fixed any time soon.

The problem is that federal graduation rates treat all completions besides bachelor’s degrees the same. For a four-year school that primarily awards bachelor’s degrees this isn’t an issue, they can be judged on the results for just the subset of students seeking that credential. Institutions that only offer programs shorter than two years also don’t have a problem since all their offerings at the certificate level. But for everyone in between it’s a jumbled and misleading mess.

To see why, look at the chart below. These are the graduation rates within 150 percent of expected time to completion for two-year institutions as reported in the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS).

It sure looks like community colleges are nearly three times worse than for-profit colleges. In fact, this is a common talking point used by both the for-profit industry and its defenders.

There’s just one problem, the two bars in the graph above aren’t comprised of the same things. At for-profit colleges, 86 percent of students counted as graduates had finished programs of less-than two years, almost certainly certificates. By contrast, three-quarters of community college graduates were in programs that were two years or longer, likely associate degrees.

Comparing the graduation rates of community colleges and for-profit colleges is effectively judging the rate at which students earn associate degrees against shorter certificate programs. This apples-to-oranges comparison is particularly problematic since one would of course expect the completion rate of shorter programs to be higher since there are fewer opportunities to drop out and no need to re-enroll for a second academic year.

The non-comparability issue is not just due to how cohorts are constructed for graduation rates. As the chart below shows, 58 percent of credentials awarded by community colleges in 2012-13 were associate degrees, at for-profit colleges they were just 27 percent of completions.

Unfortunately, there’s no great way to generate comparable graduation numbers from the current data. One option would be to exclude all non-associate degree completers from the numerator and denominator of the graduation rate. But this assumes a 100 percent completion rate for certificates and can unfairly attribute dropouts to certificates. And there’s the question of what to do about students who transferred out, a group of individuals that make up 17 percent of the graduation rate cohort at community colleges (though just 0.5 percent at for-profits).

This problem is not likely to be solved soon. Starting in 2015-16 the IPEDS surveys will be changed to include information on students who are attending part time or have transferred in from another institution. These additional data will make it possible to provide far more comprehensive completion rates. But it won’t solve the credential comparability problem. That’s because colleges will only have to report whether students earned an award of some sort, not the type of credential earned. It will actually be worse, lumping all awards from a nine-month certificate to a bachelor’s degree together.

What to do?

In the absence of usable federal graduation rate data, comparisons in the completion rate between community colleges and for-profit institutions can only be made using irregular surveys by the National Center for Education Statistics. These cannot tell us anything about individual institutions, but at least provide a comparable look.

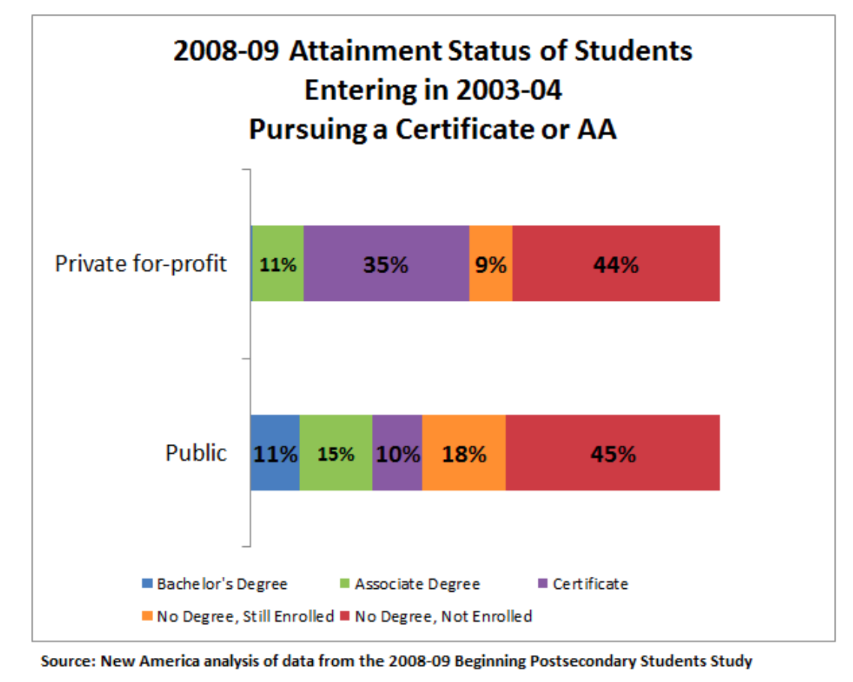

The most recent of these surveys, which tracked students who entered college in 2003-04 through 2008-09, shows that the overall percentage of students that did not earn something within six years of enrolling was basically the same at public colleges and for-profit institutions. But what students actually earned was very different.((These data are for students pursuing an associate degree or a certificate at a public college instead of focusing on a particular sector. This makes it possible to include four-year institutions that are really associate-degree-granting, another flaw in the way IPEDS categorizes institution by the highest degree awarded.))

As the chart shows, about 47 percent of students at for-profit colleges who started out seeking an associate degree or certificate earned something. That’s higher than the attainment rate at public colleges (37 percent). But because 18 percent of public college students were still enrolled—double the number of for-profit students—the percentage of students who failed to earn anything and aren’t enrolled is basically identical.

There's a big difference in what students actually came away with. Most for-profit students earned certificates and less than 1 percent earned a bachelor’s degree. At public colleges, students were split between bachelor’s and associate degrees and certificates, with more students earning degrees.

These findings open up a whole new set of debates. For example, given that we know some certificates at for-profits offer horrifically bad returns is a 35 percent attainment rate for that type of credential necessarily a good sign? And how might one weigh still being enrolled or having earned a higher credential than an associate degree?

Ideally, these are the kinds of conversations we could be having at an institutional level. But that won’t be possible until we stop treating all non-bachelor’s degree credentials the same. And until then we’ll be stuck with misleading and incomparable comparisons.