How Trump Could Abolish the Department of Education

It would be messy, but it could be done

Blog Post

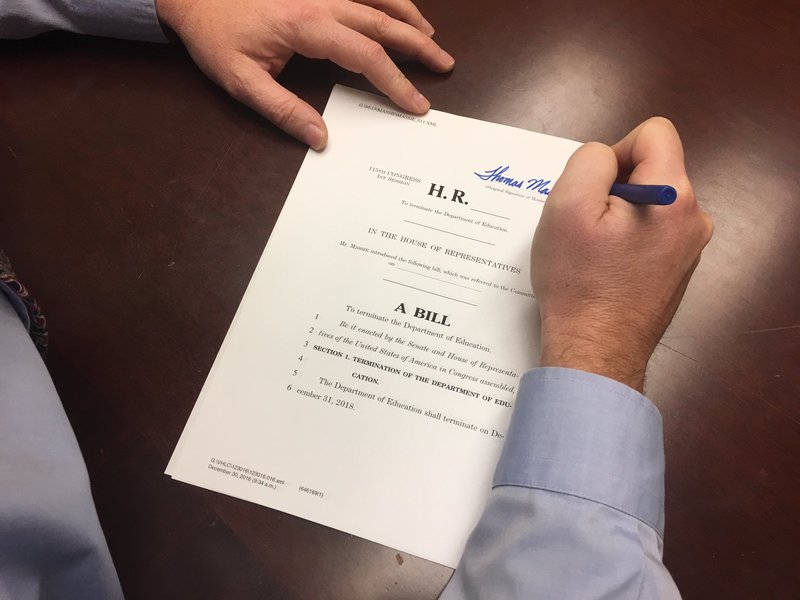

Rep. Thomas Massie / Twitter

Feb. 15, 2017

Kentucky Republican Congressman Thomas Massie loves brevity, which he demonstrated with his new one-sentence bill introduced last week: “The Department of Education shall terminate on December 31, 2018.” Massie is probably just scoring some political points, but abolishing the Department of Education is a favorite idea of Republicans, including President Donald Trump. And while elimination is unlikely, it’s also not impossible.

I’ve previously dismissed the idea of eliminating the functions of the Department of Education as fantasy—programs like Pell grants and K-12 funding for poor districts are too popular to cut. But what if there were a way to eliminate the department, as Massie proposes, without cutting these popular programs? It is possible to do. Granted, it would be a bureaucratic nightmare, expensive, and possibly lead to fraud, waste, and abuse. Eliminating a department is unlikely to solve many problems, but very likely to create a lot of new ones. On the other hand, it would be a massive victory for an administration obsessed with symbolism and changing the status quo. Based on Trump’s executive order banning travel from seven predominantly Muslim countries, this administration seems to have a much different political calculus and higher tolerance for controversy. So, here’s how Trump could abolish the Department of Education.

By dollars, the biggest thing the department does is oversee the $1.3 trillion outstanding portfolio of federal student loans and distribute $30 billion worth of Pell grants every year. Those programs could be moved to the Department of Treasury, something a number of experts have proposed. That’s because the Department of Education, whose leaders and most of its staff have mainly been K-12 focused, don’t have a lot of interest or expertise in the financing and economics of higher education. That was proven most recently when the Government Accountability Office revealed that the department had misestimated the cost of a loan repayment program by tens of billions of dollar due to incompetence. And don’t forget the only number Betsy DeVos cited about federal student loans was false. Given that Treasury doesn’t know much about higher education, the shift could create new problems. But student loans and Pell grants have been a bad enough fit in the Department of Education that even if moving the program proved costly, many would still support it.

On the K-12 side, the two largest federal programs are Title I, allocating $16 billion for schools that serve concentrations of disadvantaged students, and IDEA, sending $13 billion dollars to help students with disabilities. These billions are dispersed and monitored according to arcane formulas that few outside the Department of Education really understand. Theoretically, they could be passed to the Department of Health and Human Services, which used to administer Title I before the Department of Education was founded. But that would create bureaucratic headaches not just for the agency, but for states just as they are adjusting to new rules from the Every Student Succeeds Act. Given that Republicans want to make Title I easier for states, it’s hard to believe they would quickly get behind this idea.

However, any bill to abolish the department would give Congress an opportunity to get creative with Title I and IDEA, even if it would mean Massie might have to add a few more thousand sentences to his bill. Republicans have long wanted to either morph these programs into state block grants or make the center of the funding formula the student rather than the school. Both ideas have drawbacks: making money follow the student would replace one complicated formula with another, and block grants run the risk of being redirected to more politically powerful (and richer) school districts. One possible solution would be to turn both into HHS-administered block grants, and give the Department of Justice power to monitor patterns in school spending and take action against states if they suspect that federal funding is being diverted. The block grant approach would make it harder for the federal government to use Title I as a hammer to craft state policy, which would be a welcome development for Republicans (and states).

The $5 billion in vocational education could be administered through the Department of Labor. That agency is theoretically more focused on the challenges of workforce development in the 21st century, and could make for a better fit for those funds than the K-12-focused Department of Education. Issues would still remain, of course. For instance, much of workforce development funding actually happens through the Pell Grant program, which would now be administered through Treasury. If that complication is a problem, Republicans could propose to move the vocational funding into the Pell Grant program, using that new money to allow students to access the program for the summer months, something that would be particularly useful for adult learners looking to gain new skills.

The Office for Civil Rights has become the most controversial part of Department of Education in the last eight years. The office monitors K-12 schools and colleges for discrimination based on sex, race, national origin, disability, and age, and the Obama administration recently expanded that to sexual and gender identity as well. The department initiates investigations into schools that, for instance, have not done enough to ensure a safe environment for these minorities and can impose financial penalties and withhold federal funding. While few would argue against this role, conservatives allege that the Obama administration has used OCR as a tool to advance a culture war agenda, for instance, mandating schools to allow students to use bathrooms that conform to their gender identity. Many advocates are now concerned that Congress and Trump could defund and defang this office. But regardless of its ultimate fate in terms of funding, this office could be moved to the Department of Justice’s existing Civil Rights Division without significant cost or benefit. That agency enforces many of the same statutes as the one in the Department of Education.

As for everything else, a handful of smaller programs (varying in size from less than a million dollars to a couple billion) could be consolidated, moved around, or eliminated. As just one example, various federal pet-projects in K-12 could be consolidated to round out the academic enrichment block grant.

That’s how Trump could do it, but will it happen? Most presidents toy with the idea of consolidating parts of the federal bureaucracy, but eventually abandon the idea because the political cost is too high for agencies the president can simply ignore or marginalize. For example, President Obama’s team drew up a plan to merge the Department of Energy, Interior, and the Environmental Protection Agency, but the idea went nowhere. Furthermore, recent changes to federal bureaucracy haven’t gone great—the Department of Homeland Security, which was created in the wake of the September 11 attacks, consistently ranks at the top of the Government Accountability’s “High Risk List” of fraud, waste, and abuse.

Thus, most Republican presidents would quickly abandon the idea as a worthless political slog. And if the surprisingly contentious confirmation fight over Betsy DeVos has shown anything, it’s that Democrats can mobilize around perceived threats to public education. Given that DeVos needed Vice President Mike Pence’s tie-breaking vote to become secretary, it’s extremely unlikely Trump could get the Senate to pass the much more controversial idea to eliminate the Department of Education (which would probably require 60 votes). So it is highly unlikely that the Department of Education will go away. But that doesn’t mean Trump won’t propose it.

Donald Trump is not a typical president. He places a high value on symbolism, from his businesses’ branding to the physical traits of his cabinet picks. For someone like Trump, a real push to eliminate the Department of Education while not actually eliminating programs could be a win-win, where he can claim to have slayed the bureaucratic beast while continuing populist policies. For a president concerned about the effect of a man’s mustache on national security policy, the symbolism of closing the Department of Education may be just the place to focus his efforts.