Interview: Painting the ESSA Canvas with Comprehensive Educator Learning Systems

Learning Forward's Janice Poda and Melinda George Provide Their "Big Idea" for States

Blog Post

Shutterstock

May 3, 2017

A recent New America paper, Painting the ESSA Canvas: Four Ideas for States to Think Big on Educator Quality, includes interviews with individuals, selected for their individual and organizational expertise, that offer thoughtful, high-potential approaches to the preparation, recruitment, evaluation, development, and retention of effective educators under the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). This is the final post in a series of four that highlight the expert interviews from the brief. The interview on comprehensive professional learning systems below is with Janice Poda, a senior consultant at Learning Forward, and Melinda George, the director of policy and partnerships at Learning Forward.

New America: We’d like you to help states think outside the box on employing two of ESSA’s less detailed uses of state funds: "(x) Providing training, technical assistance, and capacity-building to local educational agencies that receive a subgrant under this part" and/or "(xxi) Supporting other activities identified by the State that are, to the extent the State determines that such evidence is reasonably available, evidence-based and that meet the purpose of this title."

If you were going to provide states with one idea for how to think big about improving educator quality within these two sections of the Title II statute, what would it be?

Janice Poda: As most Title II, Part A funds—92-95 percent—will flow to districts, the best thing that states can do is work directly with schools and districts to ensure that they are developing effective professional learning (PL) systems that enable teachers to continuously grow and improve.

[While ESSA no longer allows states to directly provide teachers with professional development (PD) with Title II-A funds,] states can provide examples, training, and support for their schools and districts, and ask the right questions to get them to think deeply about the kinds of PD they are offering and what they can continue to do to improve it. There are five key questions we think states should ask districts as part of the ESSA planning process, as they relate to professional learning. First, districts’ vision and how it aligns with the new professional development definition in ESSA. Second, how districts use data for goal-setting and for identifying areas for improvement needed. Third, how districts are aligning resources to ensure they are prioritizing focusing on the areas of greatest need. Fourth, how districts are building leadership capacity at all levels to lead a new kind of professional development. And finally, how districts can sustain the implementation of professional learning that meets the definition of PD in ESSA.

States can have the most impact here by providing a strong template for districts to develop their ideas and plans for how they will use their Title II-A funding—specifically in the area of professional learning. A good example of what this could look like is included in Learning Forward and Education Counsel’s recent ESSA toolkit for professional learning.

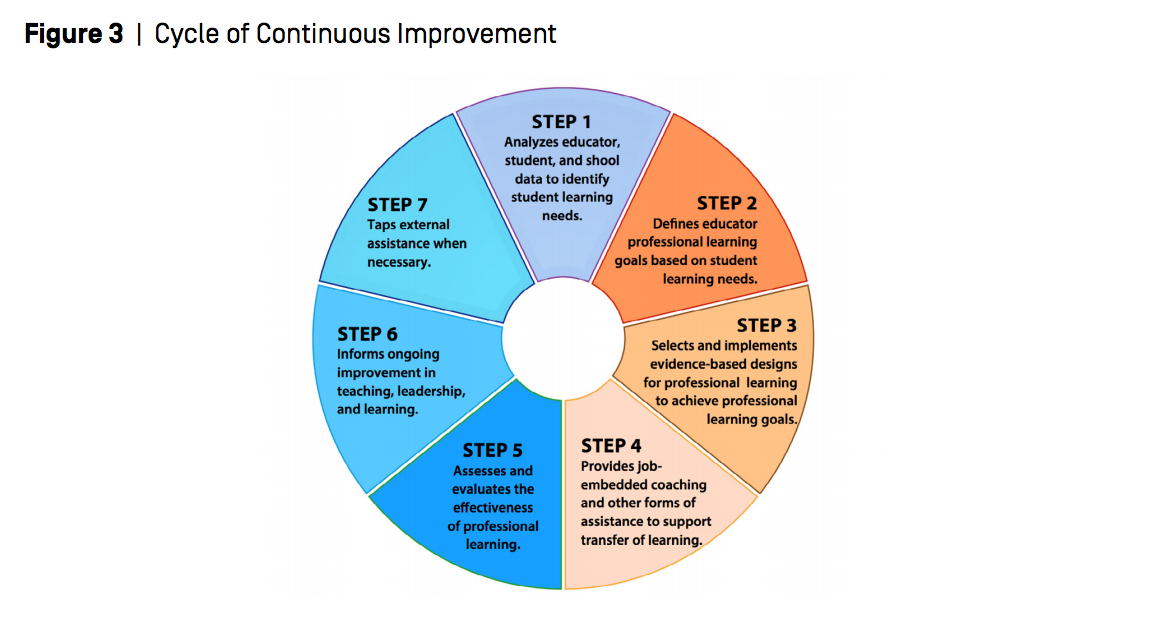

By using a template built on the questions above, districts will be able to assess, analyze, plan, and implement a system of professional learning. It also gives districts a process they can use to strategically conduct a cyclical review, similar to the cycle of continuous improvement developed by Learning Forward (see Figure below), to refine their professional learning plan.

Source: Source: "A New Vision for Professional Learning: A Toolkit to Help States Use ESSA to Advance Learning and Improvement Systems" (Oxford, OH: Learning Forward, January 2017).

Then, if states ask the districts to provide progress reports each year about what they have accomplished, they have accountability and a process to reflect on modifications needed. Of course, it’s not entirely about accountability because states should want districts to try new things, like empowering teachers to demand effective professional learning.

Melinda George: Once district plans and progress reports are submitted, states can spotlight promising and effective practices within the state that districts can learn from. States can also use the results to determine what further steps they need to take, such as developing the capacity of the district staff leading PL efforts.

NA: What evidence exists to support this idea of developing professional learning systems? Can you point to state or district examples?

JP: Few places have put comprehensive professional learning systems in place, but there are a few examples where the work is beginning to happen. As discussed in our ESSA toolkit, Fort Wayne Community Schools’ definition of professional learning serves as a vision for supporting its educators and meeting its goals for students. Fort Wayne has created quality improvement teams that include cabinet members, principal leaders, instructional coaches, and teachers. The superintendent modeled a commitment to learning by making public her professional learning goals, and established district learning communities with school leaders focused on defining effective leadership and designing and implementing professional learning. In these learning communities, principals co-observe and discuss problems of practice together, and teachers engage in regular peer collaboration to plan lessons and assessments and analyze student data together.

And Delaware is a good example of a state trying to help schools put this type of PL model into practice. Beginning with Race to the Top funds, the State invested in essential training and support in making the transition to the Common Core standards. Annually, the state releases a request for proposal (RFP) to schools to support the implementation of the Common Core standards through professional learning that is grounded in the Learning Forward professional learning standards, and a cycle of inquiry focused on continuous improvement. For participating schools, Delaware provides training in building teacher leader and principal capacity, in addition to strategic consulting partners and other follow up supports to help schools plan, implement, review, and then modify plans based on what they’ve learned.

Delaware is also helping schools focus less on educators’ reactions to the training and more on the impact of that training on teacher practice and student learning. In 2016-17, 21 schools participated in the initiative and used Thomas Guskey’s five critical levels of professional development evaluation (a deliberate process to evaluate if the PD being offered is having an impact) to assess their efforts. These schools will convene to share their findings toward the end of the school year, and a report on the outcomes of the initiative will be released later this year.

MG: States can review a recent report from The National Commission on Teaching & America’s Future, What Matters Now—The Evidence Base to see how professional learning systems can work. And Learning Forward has developed the Oxford Bibliographies that highlights evidence-based PD strategies.

Included in these resources is a key piece of evidence, from an Institute for Education Sciences review of research, that a sustained focus on professional learning works. They found that PD strategies that involved 30-100 hours of learning over the course of 6-12 months boosted student learning by about 21 points. But they also found that 14 hours or less of PD has no impact on student learning.

NA: Do you see this area of Title II intersecting with other areas of ESSA? If so, how should states think about coordinating their efforts here? Are there examples of states already doing this?

JP: The term professional development is used over 60 times in ESSA and is threaded through all the Titles. And professional learning is at the heart of school improvement work. Often support for school improvement relies on new technology, new curriculum materials, and short-term leaders to work with school principals, but seldom do those supports focus on building the capacity of teachers that are already there. To help schools improve student learning, professional learning must first improve teacher practice.

MG: It’s important for states to take the lead on thinking about how the different components throughout ESSA intersect. State leaders should be rethinking how state education agencies and districts have traditionally been staffed, and instead of the traditional silos, start thinking about these entities as one big learning system. Establishing a learning system is about integrating the different strands within the education system; for example, bringing together people from Curriculum & Instruction and Human Capital departments to focus on teaching and learning.

JP: Tennessee has done good work on effectively aligning resources for PL. The state created a comprehensive guide for districts on coordinating funds from multiple sources. It includes a detailed overview of funds for a wide variety of goals, including improving literacy and numeracy, providing instructional coaches, redesigning school time, and upgrading curriculum. The guide also identifies potential barriers to coordinating funds and helps districts navigate these barriers.

NA: What are potential obstacles or challenges to implementation that states should be aware of, and can you provide any suggestions for side-stepping them?

MG: One big obstacle is time. You don’t often see sufficient time provided to do the necessary reorganization, and this is prevalent at all levels, school, district, and state. I would argue though, that you could cut back tremendously on the time needed if you simultaneously worked with all of the levels to make a system-wide change instead of doing it through a trickle-down process (that is, first state, then district, then school). States can build the capacity of leaders at every level to participate in the change process, and by doing so, get closer to creating this learning system rather than advocating for it from one level to the next, and then to the next.

JP: The greatest problem—and where states and districts experience the biggest challenges—is in the actual implementation of these systems and sustaining of that implementation.

States can assist districts with implementing the strategies in their ESSA plan by utilizing change management. States and districts should take the time upfront to reflect on and audit what they have been doing for professional learning and determine what meets expectations and should be continued, and what needs to be changed. States and districts should outline how evidence of impact of professional learning will be collected and analyzed to ensure they are making a difference in teacher practice, and ultimately, student improvement.

A recent report from Frontline Education, Bridging the Gap, stated that only about 20 percent of current PD being offered in districts meets the new definitions of professional learning in ESSA. So, after reflecting on what kind of PL states and districts are currently offering and where they are seeing impact, states should consult the new definition to see where remaining gaps are and strategize best practices for changing their PL accordingly.

This will help states get started, but they need to make sure that they continuously look at the results of professional learning to determine the strengths and weaknesses and the impact it is having on teaching practice.