The ‘Trial and Error’ of Teaching Pre-K Special Education in a Pandemic

Special education pre-K teachers are trying everything they can to build connections with their students. Against all odds, some are succeeding.

Blog Post

Jessica Kershner

Nov. 30, 2020

Maureen Casey teaches special education pre-K students in San Jose, CA. Many of her students are on the autism spectrum. With in-person school still closed, Casey teaches three different Zoom classes each weekday and also provides activities families can do with children on their own. During these Zoom sessions Casey sings songs, plays games, reads books, and helps her students identify feelings and patterns.

“We are kind of learning as we go,” Casey said. “I am learning a lot just by watching the kids, what they are interested in, what they do naturally.” She said she often thinks up multiple ways to do the same game or activity and sees which works best. “I don’t give up, I keep trying.”

Prekindergarteners with special needs face perhaps the biggest barriers to online learning of any group—they can’t read, aren’t computer literate, and they learn best through in-person daily interactions with caring adults and peers. Yet these are the exact things that are not available to them during the pandemic.

“There is no research or pedagogy that says this is how you teach children with special needs online, because nobody thinks that’s a good idea,” said Theresa Lozac'h who is the site administrator at Burbank Preschool and Diagnostic Center in Oakland Unified. “But it’s what keeps children safest.”

There are over 800,000 children in the United States between the ages of three and five served under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Most of these children are on the autism spectrum, have developmental delays, or speech and language impairments. In California, many of these children are also dual language learners.

Federal funding requires states to provide equal education to all students, which for special education students often means providing developmental interventions like speech or occupational therapy. Research shows that pre-K can be a particularly powerful intervention, helping children with special needs make important gains in cognition, communication, and social emotional skills more quickly. Research also shows that children tend to make bigger improvements when they are in inclusion settings with their typically developing peers. But this is one more thing many of these children are not getting due to the coronavirus pandemic.

“They are really missing out right now without having those peer models,” Casey said. She suggests families engage their children in social games like tag or passing a ball back and forth to learn things like turn taking and communication, but those are unlikely to make up for the daily time missed in class.

“They are losing that practice. That knowledge that if you want someone’s attention you have to ask for it,” said Kathy Rohrer who teaches special education pre-K students in Oakland. “When you are in class, if you ignore someone they are going to walk away, you figure that out after a while. If I really want to play with them, what should I be doing?”

This is the kind of social time that children with special needs learn from because they are able to practice taking turns, regulating their emotions, and communicating their needs and feelings. That is all very hard to practice virtually. Rohrer said teachers are trying to create those experiences for kids by, for example, doing a puppet show on Zoom, where the puppets want to play together or need to share, but she says, “It’s just so artificial.”

Jessica Kershner who teaches at Acorn Woodland Elementary in Oakland said her Zoom classes work better when students can use their hands and have common materials.

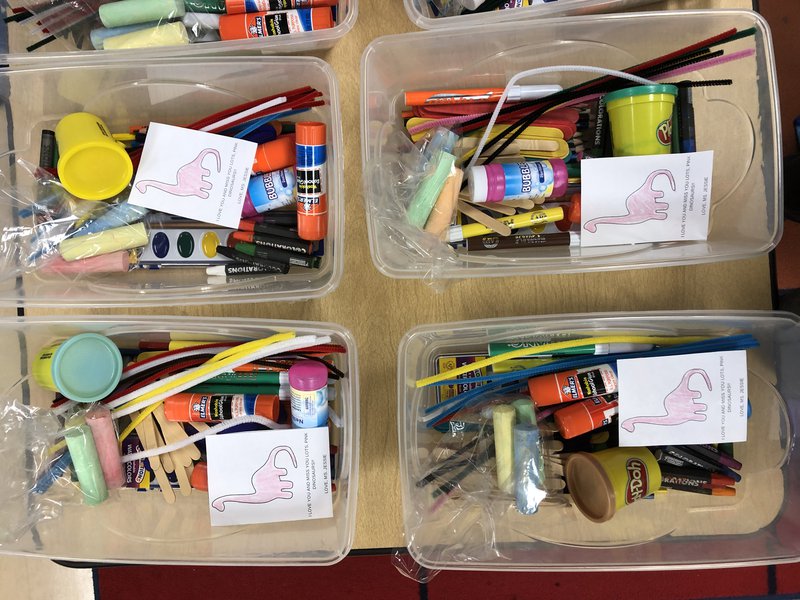

Teachers in San Jose, Oakland, and other districts in the state have been making a huge effort to get materials out to families. These have included art supplies for the coming week (scissors, glue, paint, playdough, and pipe cleaners), materials for dramatic play and music (tambourines, egg shakers, and scarves), and visual aids like cards that help students identify emotions, set routines, and learn their letters. Most schools have centralized pick up locations for families. Lozac'h said a lot of teachers are also choosing to drop supplies off at families’ homes, sometimes against local health advisories, because they feel it’s just that crucial that students access materials.

Attention at Zoom classes is often spotty, teachers say, as families balance the social and economic challenges of living through a pandemic.

Kershner has a student who she has not met at all in person or virtually and who has refused to come to any of the Zoom sessions. Kershner is working closely with the parent to come up with strategies to manage the child’s increasingly challenging behavior and to connect the child to virtual school and support services. “He is having the hardest time,” Kershner said. “We’ve tried different strategies to get him to want to join in. I sent him a personal video, and then when he didn’t want to watch it, I sent him a picture I drew in the mail.”

Families are also struggling with access to technology, insecure housing, and balancing childcare and work responsibilities. Teachers say children are being left in the care of grandparents or other relatives when parents go to work. And there are lots of children who are not able to show up for classroom Zoom sessions or therapeutic services online because it is simply too much for families to juggle.

“We have families who have five kids on Zoom at home and the bandwidth won’t handle the preschooler,” Lozac'h said. “If you’re going to choose between the middle schooler and the preschooler getting an education, a lot of people will choose the older child. Our kiddos are generally the last to get online in families that are larger. People are making these awful choices because they have to.”

Teachers have prioritized weekly one-on-one Zoom meetings or phone calls to help build relationships and trust and to educate families on how to best support students. They are also holding Zoom sessions at varying times of day. Some teachers are holding virtual breakfast dates with kids or 7:00 pm Zoom story hours so families who work during the day can attend.

Despite these efforts, learning to communicate through a screen remains a big challenge. “Up until this time, screens have been for watching,” Lozac'h said. Young children with autism specifically, struggle to understand that the screen can be an interactive experience. One teacher told the story of a child who after six or eight weeks of Zoom classes finally noticed a friend in one of the other rectangles, who had been there all along.

“It’s another cognitive leap to understand that not only can I communicate with my teacher, but I can communicate with these other rectangles,” Lozac'h said, “but the time it takes to make those connections is super long. Our families sometimes give up because it’s so tiring and hard. So only the families that are hanging in are getting to see some benefit.”

Evaluation and assessment have been very challenging to do remotely. Some districts have been evaluating students in person, but they are slow going, partly because of all of the cleaning and sanitizing that has to be done in between students. Administrators are concerned about being out of compliance with students’ Individualized Education Plans because of these delays in testing and are hoping for more standardized guidance and extensions from the state.

Meanwhile, while they navigate remote learning, teachers in Oakland and San Jose are simultaneously preparing for in-person instruction, likely in small stable groups.

“When we bring them back we are going to have work to do,” Lozac'h said. "We are going to have to make up for the time we've lost somehow, their needs are going to be so much higher.”

Enjoy what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter to receive updates on what’s new in Education Policy!