Wagner Group Contingent Rusich on the Move Again

Blog Post

Jan. 26, 2022

Pentagon claims that it has knowledge of Russian plans to preposition a group of covert operatives to conduct false-flag operations inside Ukraine as a pretext for invasion have rightly set Washington, Brussels, Kiev, and the world on edge. With tensions mounting between the White House and the Kremlin over the 100,000-plus Russian troops now massing near Ukraine’s border with Russia and Belarus, there have already been fresh signs online that contingents of Russian soldiers of fortune linked to the Kremlin-backed Wagner Group are on the move across the region.

On Friday, Alexander Borodai, a Russian lawmaker who has backed Wagner Group mercenaries with the St. Petersburg-based soldier of fortune contingent known as Rusich and the former prime minister of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People's Republic in eastern Ukraine, told Reuters that Russia’s parliament was preparing to recognize the independence of two breakaway regions in eastern Ukraine–Donetsk and Luhansk. Such a move would undoubtedly ratchet up tensions between Russia, Ukraine and NATO even further, and could spark a military response from Ukrainian leaders in Kyiv.

In Ukraine, there have been also been growing signs since at least September that a Wagner Group contingent that Borodai has backed for years has designs on a return to the Ukrainian front. Known as Rusich, or Task Force Rusich, the Russian mercenary cadre earned a reputation for its self-declared neo-Nazi ideology and brutality when it first deployed to eastern Ukraine during peak fighting between Russian separatist forces and the Ukrainian military in the summer of 2014. Now it seems Rusich has set its sights on the strategically important eastern Ukrainian city of Kharkiv. If true, it could mean the Wagner Group will be well positioned for the opening salvo in what many fear may be the prelude to a U.S.-Russian war.

A return to Ukraine?

Rusich left Ukraine in the summer of 2015, a few months after UK, Canada, and European Union sanctioned one of the group’s commanders, Alexey Milchakov, after reports of his unit’s involvement in alleged war crimes in Donbas. Sightings of Milchakov, and Rusich’s lead military trainer Yan Petrovsky in Syria have since cropped up in multiple reports about their exploits over the last seven years, including the grisly torture and dismemberment of a Syrian prisoner.

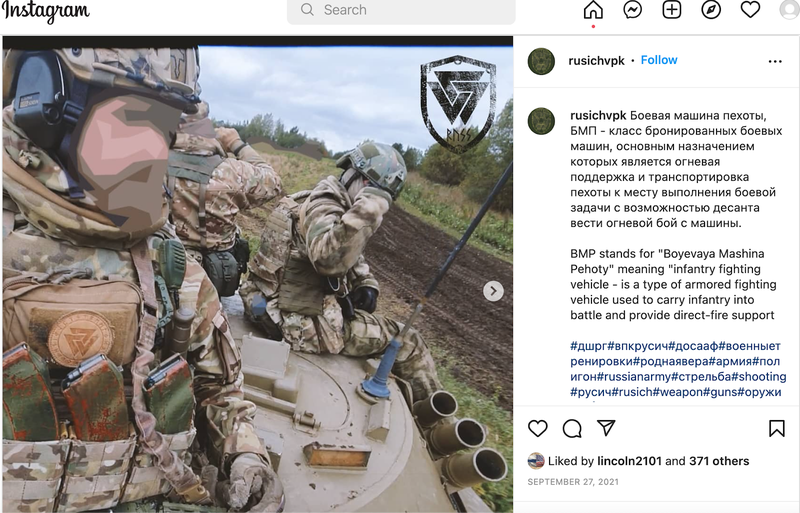

But more recently, rumblings about Rusich’s possible return to the Ukrainian front for a “Russian Spring 2.0” assault deeper into Donbas first surfaced online on the contingent’s Instagram account early last year. The first mention appeared in a post made by a follower of the account on January 5, 2021. Several months later, on September 27, 2021, the group indicated in another post depicting a stylized selfie photo post of its members atop a Russian armored vehicle that they were training for military exercises. “BMP stands for "Boyevaya Mashina Pehoty" meaning "infantry fighting vehicle - is a type of armored fighting vehicle used to carry infantry into battle and provide direct-fire support,” the post declared. The September Instagram post also referenced a Russian military veterans club and military training exercises and received 371 likes from account followers.

Figure 1: On September 27, 2021 Rusich posted a selfie of its members mounted on a Russian made BMP armored infantry fighting vehicle on its Instagram account under the handle @rusichpvk. The post referenced a Russian military veterans club and military training exercises and received 371 likes from account followers.

One month later, on October 28, 2021, a comment to Rusich’s Instagram account made clear that the soldier of fortune contingent had designs on a return to Kharkiv. In comments posted in response to the battlefield selfie, a user named @anton_lvr asked if Rusich planned on another deployment to “DNR/LNR,” shorthand for the Donetsk People’s Republic and Luhansk People’s Republic, the two Russian-separatist controlled districts of Donbas.

The reply from Rusich was brief: “@anton_lvr хнр, кнп, и т.д.” ”KhNR” refers to the city of Kharkiv, the scene of multiple, protracted battles from 2014 to 2015 during the Kremlin-backed separatist onslaught in Donbas. “KhNR” or хнр is short for “Kharkiv People's Republic,” which pro-Russian separatists briefly proclaimed in 2014 before Ukrainian forces reasserted control over the city.

Figure 2: On October 27, 2021, Rusich Instagram follower @anton_Ivr asked in the above post to the group’s account whether the soldier of fortune contingent planned to return to Ukraine.

The reference to a possible return to Donbas was not the first time that Rusich was asked whether another “Russian Spring 2.0” might be in the offing and whether Rusich would redeploy to Donbas. In a post dated January 5th, 2021, user komstantinsamoilov, a private account on Instagram, asked the user if they would return to the Donbas if war was to break out. But there was no reply.

Figure 3: Rusich Instagram follower @komstantinsamoilov asks if Rusich will return if war breaks out on January 5th, 2021.

The radio silence from Rusich could be because the Wagner Group subunit was busy with one of its other main missions–protecting state owned and Russian financed oil and gas infrastructure near Palmyra, Syria. On April 27, 2020, Rusich uploaded a looping 23 second video showing the outskirts of an unknown city. A closer look at the video shows many clues as to where the video was taken. Topography, a road sign, and the geotagged photo help place the video on the outskirts of Palmyra.

Figure 4: A comparison of still frames from an April 2020 Instagram video on the Rusich Instagram account with Google Earth satellite imagery.

Although the brief mention of Kharkiv seems enigmatic, it is par for the course for Rusich. Since the start of the Russian incursion in Crimea and Donbas in 2014, the group has garnered a reputation for showy displays of battlefield bravado online. Initially, Rusich commanders Milchakov and Petrovsky, as well as others in the group, contented themselves with posts to a Rusich group page on Vkontakte, a Facebook-like social media platform that is popular in Russia and Eastern Europe. In 2017, the group branched out to an Instagram account, which remains active today.

A freighted history and a history of violence

Now commonly called simply Rusich, the contingent was better known when it was first formed in St. Petersburg in 2014 by its official name: the Diversionary Guerilla Reconnaissance Group Rusich (ДШРГ Русич/DShRG Rusich). The group’s name is a triple-entendre. It is a reference to the mythic Medieval fortress, or “sich,” of “Rus,” the pre-imperial confederation of Norse peoples who hailed originally from Sweden and settled the territory that lies between the Baltic and Black Sea.

“Rusich” is also likely a reference to a popular 2007 battlefield video game of the same name: “8th Century Rusich-Glory or Death.” Perhaps not coincidentally, the hero of the game is Alexander Nevsky, the mythic Medieval military commander who saved St. Petersburg from invasion in the 8th century. Interestingly, one of the group’s founding members, Alexey Milchakov, also served in the Airborne Troops (VDV), a key feeder for Wagner Group fighters, many of whom, in the first wave of deployments in the early 2000s, fought with the special operations forces of the 7th Squad of Special Forces (“ROSICH”), as we have documented in detail.

With roots in St. Petersburg’s ultranationalist and neo-Nazi scene, the group carried out reconnaissance and sabotage operations behind enemy lines in Ukraine and played a significant role in several key battles during the early part of the Donbas conflict. By Milchakov’s own account on his Vkontakte social media page, he and Petrovsky formed the group in the summer of 2014 after graduating from the “Partizan” paramilitary training program run by Russian Imperial Legion, the fighting arm of the St. Petersburg-based and U.S.-sanctioned Russian Imperial Movement, or RIM. The group famously fought alongside Russian separatist commander Alexander “Batman” Bednov before he was killed in an ambush.

During this time, Rusich acquired a reputation for exceptional brutality. In September 2014, Rusich attacked a column of Ukrainian volunteer fighters near the Donbas town of Metallist, killing dozens, according to Ukrainian news reports. Afterward, local sources said that Rusich members mutilated and set fire to the dead, images of which circulated on the web and became part of the group’s mythos. Throughout their 2014-2015 deployment, Milchakov, Petrovsky, and other Rusich members courted infamy, posting images of atrocities (warning: graphic) and selfies with dead bodies, according to Ukrainian media. Ukrainian human rights groups also accused the contingent of torturing prisoners of war. Rusich’s outsized social media footprint served as useful propaganda, hyping members as fearsome warriors and belying their relatively small numbers in Ukraine during the 2014-15 period.

Rusich withdrew from Ukraine in 2015, only for members to reappear in Syria, guarding strategically important oil and gas infrastructure belonging to state-backed Russian firms, as we and Novaya Gazeta first reported in 2019. Posts to the group’s Instagram account showed members in the Palmyra region of central Syria, not far from the al-Shaer gas field where Russian security forces seemingly linked to the Wagner Group filmed themselves torturing and killing a Syrian army deserter named Hamdi Bouta in April 2017. Later that year, Russian news site Fontanka identified Milchakov as one of several private military contractors swimming in a pool near Palmyra. In October, the Atlantic-Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab located Petrovsky in Syria around the same time.

Figure 5: Photo from Rusich’s Instagram of a soldier posing near the ancient ruins of Palmyra, Syria, April 2019.

Part of a larger network

Rusich’s social media activity on Instagram and VKontakte indicates the Russian contingent is deeply embedded within a larger network of ultranationalist fighters, and the group appears to have ready access to government resources. Following Hamdi Bouta’s 2017 death, an analysis by New America found extensive overlap between Rusich’s online circles and those of both VDV airborne paratrooper units of the Russian military and the Russian Imperial Movement. Yet, Rusich’s ties to a broader constellation of far-right and government entities goes beyond shared online communities.

In December 2020, Rusich uploaded a video to Instagram showing Petrovsky, Borodai–the Russian lawmaker and pro-Donbas separatist leader–and recruits conducting firing drills with members of the Union of Donbas Volunteers, or SDD, an organization for Russian veterans of the Donbas war that enjoys close relations with Putin’s United Russia party. In the video, Borodai calls the participants “real Russian patriots,” and he emphasizes the importance of such groups for Russia’s national interest.

Instagram posts show that Rusich returns regularly to what appears to be the same firing range, its telltale blue-roofed gazebos most recently appearing in a post on the group’s account from January 15, 2022.

The Partizan Center, which provides military training for the ultranationalist Russian Imperial Movement, appears to use the same facility. A post to the Partizan Center’s Telegram channel on May 3, 2021, listed an address for an upcoming training at a shooting range in St. Petersburg’s Kolpino district.

Figure 6: A May 2021 post on the Partizan Center’s Telegram channel advertises an upcoming training at a shooting range in the Kolpino district of St. Petersburg.

A comparison of still frames from Rusich’s Instagram video post with satellite imagery from Google Earth of the shooting range referenced in the Partizan Center’s post suggests that the two facilities are, in fact, one and the same.

Figure 7: Comparison of Google Earth satellite images of the Partizan Center shooting range with the one that appears in Rusich’s Instagram video.

The Partizan Center post refers to the range as the “shooting range of the Ministry of Emergency Situations,” known internationally as EMERCOM, a Russian government agency that oversees the country’s emergency services. An online search yields dozens of results using the same language to describe the Kolpino range, including an official site for the St. Petersburg city government. It is adjacent to a public shooting range called Severyanin, with the two facilities sharing an entrance.

The location of the shooting range in the center of the special district reserved for EMERCOM operations and administration in the St. Petersburg region is highly significant. Long a sinecure of Russia’s siloviki security elites, EMERCOM was among the first agencies to experiment with quasi-privatized military operations in Russia. During the period when Russia’s current defense minister Sergei Shoigu headed EMERCOM, dozens of military contractors deployed under the auspices of a company called EMERCOM Demining to the Balkans to conduct demining operations aimed at clearing a path for a gas pipeline across southeastern Europe, according to reporting by the OCCRP.

From 2001 to 2012, a former KGB agent close to Shoigu named Oleg Belaventsev ran the demining company, according to OCCRP. During that time a contingent that was an early progenitor of the Wagner Group and Rusich, Antiterror Orel (“Antiterror Eagle”), was among the first to take up demining contracts in the Balkans. Later, state-backed soldiers of fortune with the company deployed to the breakaway region of South Ossetia in the former Soviet republic of Georgia, and in 2017 they carried out demining operations in Crimea, according to an agency webpage. Demining troops or “sappers,” firefighters, and specialists in biochemical hazard response were notably well represented in documentation of Wagner Group travels to Syria in leaked data we reviewed from the Dossier Center, an investigative organization funded by former Russian oil magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Today, Belavantsev, who once also served as deputy director of Rosvooruzhenie, Russia's primary arms trading agency, is Russia’s chief envoy in Crimea.

In March 2018, April 2019, and again in October 2020, the Rusich Instagram account posted photos of members carrying out parachute jumps, in the latter two cases from an Antonov An-2 aircraft, which the Russian military has historically used as a training aircraft for airborne divisions. Moreover, the April 2019 photos are geotagged to the city of Pskov, where the 76th Guards Air Assault Division, an elite paratrooper unit, is garrisoned. Both Rusich leader Alexey Milchakov and Dimitri Utkin, the titular commander of the Wagner Group, served in the 76th Guards.

We compared the airfield visible in the Rusich photos to satellite images of airports in the Pskov region and were able to confirm that Rusich members were training at Sorokino, which local sources describe as the 76th Guards’ military airfield.

Figure 8: Comparison of satellite images of the Sorokino airfield with posts from Rusich’s Instagram account.

Taken together, Rusich’s apparent access to government facilities and links to other far-right organizations paint a picture of a well-connected Russian soldier of fortune contingent with at the very least tacit Kremlin backing and friendly ties to the state, if not outright under direct state control.

“Alone you will kill the ferocious snake”

After the October 2021 Instagram comment in which Rusich hinted at a return to Kharkiv, the group’s account went silent - remarkable in itself for an organization that has often cultivated attention via social media. Then, on January 15, 2022, the day after the White House accused Russia of planning a false-flag operation in Ukraine as a pretext for invasion, Rusich’s account lit up. Along with photos of recruits conducting winter training at what appears to be the same St. Petersburg firing range, Rusich posted a quote from the Edda, a cycle of ancient Norse poems that is popular among the European far-right:

Alone you will kill

the ferocious snake,

on Gnitahade he

lies, insatiable.

The quote is classic Rusich: ominous, vague, with undertones of glory and violence. As Russia readies for war on the Ukrainian border, it appears that one Russian militia contingent is preparing for the next chapter of a war it played no small part in starting.