Three inextricably linked challenges within our existing early education and care system emerged over the course of our research: the high cost of care for families, the impoverishment of caregivers, and the rocky transition to kindergarten for children. Integrating the care of three- and four-year-olds into the K-12 public school system is one way to address these issues.

Primary school usually and arbitrarily begins at age five in the United States, even though brain science shows that children are learning long before they enter the kindergarten classroom. High quality universal pre-K for three- and four-year-olds could significantly reduce the financial burden facing families with young children and help ensure that children are prepared for kindergarten. We recommend all three- and four-year-olds have access to optional, publicly-funded pre-K, as they do for kindergarten through twelfth grade, and that that pre-K be of a certain uniform standard for quality.

High quality universal pre-K for three- and four-year-olds could significantly reduce the financial burden facing families with young children and help ensure that children are prepared for kindergarten.

Why publicly funded? Because the price tag of high quality pre-K and child care keeps it out of reach for many families. The Care Index found that the average cost of care for a four-year-old in a center in Illinois is $10,414, about 19 percent of the median household income in the state, and 61 percent of the income earned by a single parent working for minimum wage. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services defines affordable child care as no more than 10 percent of a family’s income. Universal pre-K for three- and four-year-olds would save families thousands of dollars and improve their economic well being. Most children today grow up in households where all parents work outside of the home, making outside care a necessity. Tuition-free pre-K would reduce the burden placed on parents struggling to afford care for all hours of their work day.

According to the highly respected National Institute for Early Education Research’s (NIEER) most recent data, last year only 41 percent of four-year-olds and 16 percent of three-year-olds were served in some type of publicly funded pre-K program. The federal government has been providing pre-K to low-income three-and four-year-olds through the means-tested Head Start program for over 50 years. Head Start offers comprehensive services, including but not limited to high quality pre-K education, health and developmental screenings, parenting classes, connections to social services, and more. Head Start is the nation’s first and largest pre-K program. It reaches approximately one million children, but, due to limited funding, does not even serve half of those who are eligible.

Another 1.4 million children are enrolled in state-funded pre-K programs. Many states and local governments have been expanding access to pre-K in recent years through a hodgepodge of public and private programs. However, there is great variation in how states prioritize early education. For example, West Virginia provides universal pre-K for four-year-olds and pre-K for three-year-olds with disabilities. Oklahoma’s well-known pre-K program serves about 75 percent of four-year-olds and no three-year-olds. Other states, like Washington, provide pre-K only to the state’s most vulnerable children. In contrast, a handful of states, such as New Hampshire and Montana, still do not have a state-funded pre-K program at all.

In some cases, local school districts have led the way for pre-K in their states and others have built on their state pre-K programs. Boston Public Schools, for instance, has a highly-regarded universal pre-K program that is much more expansive than the state’s program. The District of Columbia is another district to look to as an example—the district serves an impressive 86 percent of four-year-olds and 64 percent of three-year-olds in public pre-K. While access to programs nationally varies significantly based on a family’s zip code, the quality of programs varies even more.

But it shouldn’t. Low quality pre-K and child care programs fail to adequately prepare children for kindergarten, and when children begin kindergarten behind it is difficult to catch up. It’s no secret that our public education system is failing a significant portion of our students—according to the Nation’s Report Card, only about one-third of American children can read proficiently by fourth grade. Research has revealed time and again that access to high quality pre-K benefits children in school and later in life. Children who attend strong programs not only perform better in kindergarten, but are also less likely to be placed in special education, less likely to repeat a grade, more likely to graduate from high school, and even less likely to commit crimes. While universal pre-K can benefit all children, it has the largest impact on those from low-income and minority families as well as dual language learners who are most likely to begin school already behind their more advantaged peers.

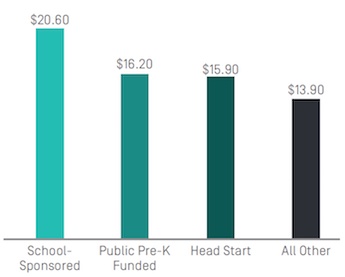

In addition to improving access for families and outcomes for children, universal pre-K has the potential to alleviate other issues plaguing our current early education and care system. One of the largest challenges to providing quality care is the low compensation of caregivers. While public funding for pre-K programs does not guarantee higher wages for pre-K teachers, it could be a step in the right direction. Currently, teachers and caregivers who work in publicly funded settings, particularly school-sponsored or public pre-K, earn higher wages than those working in other settings (see graph below). A handful of states require pay parity for pre-K and K-12 teachers if the program is located in a public school. Paying pre-K teachers a living wage is essential to sustaining a high quality program.

The Obama administration has made a large push for expanding pre-K. The President’s proposed Preschool for All initiative would provide pre-K to four-year-olds in all low- and middle-income families through a combination of state and federal dollars. While Preschool for All did not and will not become a reality under this administration, President Obama did encourage and assist states in expanding and improving their pre-K programs through other means. The competitive four-year Race to the Top: Early Learning Challenge grants allocated $1 billion to helping states develop their birth to five early learning systems. The competitive four-year Preschool Development Grants specifically help states develop infrastructure and expand seats for four-year-olds as well as improve the quality of pre-K offerings. Finally, the newly authorized K-12 education law, the Every Student Succeeds Act, includes language encouraging more coordination between pre-K and K-12 to improve transitions for children.

Teachers are the key to a high quality program and they need to receive training, feedback, support, and compensation that’s comparable to K-12 teachers to best serve their students.

There is no one right way for policymakers to develop a high quality pre-K program. However, there are certain criteria that research has shown are associated with stronger child outcomes. The National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) has identified 10 quality benchmarks as a baseline for building high quality pre-K programs:

Comprehensive early learning standards

Bachelor’s degrees required for lead teachers

Specialized training in pre-K for teachers

Assistant teachers with CDAs or equivalent

At least 15 hours/year of professional learning

Maximum class size of 20 students

Maximum staff-child ratio of 1:10

Vision, hearing, and health screenings for children, and at least one support service

At least one meal per day

Regular site visit monitoring

While pre-K can and does take many different forms throughout the United States, we propose that publicly funded pre-K should ideally include the following components in addition to meeting NIEER’s current baseline benchmarks of quality:

Universal access for all three- and four-year-olds with an emphasis on serving those with higher needs when resources are limited

Full-day programs that align with the K-12 school day so that children have sufficient time to learn and play, and so that parents’ work schedules are minimally impacted

Sufficient funding to provide high quality services and a stable funding stream that is less vulnerable to cuts

Well-prepared and well-paid teachers who receive the training and support they need to succeed in the classroom

Coordination with elementary school principals and kindergarten teachers to ensure instructional alignment and ease transitions from one year to the next