Participatory Planning to Build Stronger Early Childhood Policy and Programs

Brief

New America/Shutterstock

Dec. 11, 2024

The New Practice Lab convenes the Early Care and Education Implementation Working Group, a group of early care and education leaders from across the country. They are committed to delivering high-quality early childhood services to families—and know that implementation is everything. This is the third brief based on lessons from this group; see our prior briefs on Family Outreach and Centralized Enrollment for a deep dive into some of the findings from the initial working group cohort.

Policymaking for the People, by the People

Including people in policymaking is core to American identity—after all, resistance to “taxation without representation” led to the Revolutionary War. Even so, policymaking too often happens among small groups of people, behind closed doors. This can lead to poorer design, worse outcomes, and a sense that government is a force to be reckoned with rather than a partner in problem solving. The New Practice Lab—a partner in the work of the Implementation Working Group—has long championed the participation of people in policymaking, most recently focusing our efforts on families with children under the age of six. Our colleagues in New America’s Political Reform program have advanced the case for participatory democracy processes and co-governance models around the world.

“When more people enter into democratic processes to help design and implement policies and programs, those experiences increase confidence that government works for all of us.”

At the federal level, the establishment of a national framework for participation and the Life Experiences effort, led by the Office of Management and Budget but taking a “whole-of-government” approach, is reorienting government services and benefits to the needs of people. However, municipalities are often labs of policy innovation, and it is unsurprising that models for participatory government are developing at the local level. Whatever the level of government, when more people enter into democratic processes to help design and implement policies and programs, those experiences increase confidence that government works for all of us.

What Is Participatory Planning?

One mechanism for increasing civic engagement is “participatory planning,” a practice growing across an array of places and policy issues. In this brief, participatory planning means bringing impacted people directly into policymaking and decision-making conversations and empowering them to shape the outcomes. People use different terms for this work, such as family and community engagement, community planning, collaborative governance, collaborative planning, and community empowerment.

There are a few reasons for the growth of participatory planning, including a growing appreciation that the people most impacted by policies should have a voice in their outcome—brought on in part by an increased recognition of long-standing structural racial inequities—along with the adoption of technology tools that help enable greater participation. There are many examples of participatory planning across public policymaking. One approach is participatory budgeting, a process in which community members have direct input into how to spend part of a public budget. Participatory planning is also common in land use processes, when a community and its leaders decide how to proceed with new development projects. Increasingly, these practices are spreading to other areas—including early childhood education.

When done well, participatory planning:

- Is designed to be feasible, accessible, and authentic, so that those that are most impacted are able to meaningfully participate, including recognizing and responding to how past efforts may have generated distrust and barriers;

- Meaningfully engages community members prior to final design and decisions, such that impacted communities’ input and efforts are incorporated and valued;

- Transparently structures process such that community members understand the scope of the collaboration, and which decisions may be made internally following input and co-design periods, and how and why this will be done; and

- Incorporates community ownership and leaders in a manner that builds collective knowledge, empowering and enabling more effective and efficient implementation and delivery once decisions are made, as well as establishing an ongoing cadence for feedback and improvement.

Why Pursue Participatory Planning When Designing Programs and Services?

There are several reasons to pursue participatory planning. First, working with people most directly affected by a policy during both planning and implementation gives administrators the best chance to design solutions that address the actual problems and needs of the people served. By involving the most impacted people, governments can build better solutions, spot and mitigate delivery risks early on (thereby reducing costs and delays), incorporate feedback and adaptability into programs, and even inspire public sector workforces to be more mission-oriented. When structured and implemented well, participatory planning creates the conditions for deeper, longer-term change by enabling impacted groups—particularly underserved communities—to “assert their views, hold governments and other actors to account, and claim a share of governing power.” Programs designed in collaboration with communities may be better equipped to withstand shifts in political winds. And finally, participatory planning can help teams meet legal requirements or build legitimacy. Participatory planning is required in some situations, and laws or regulations may require the consent of a group to move forward. Even without formal requirements, policymakers may need to demonstrate consent from an impacted group to get buy-in from the press, elected officials, or other crucial stakeholders.

Participatory Planning in Early Care and Education Programs

While participatory planning can be relevant across many types of policymaking, there are a handful of reasons why it specifically matters in early childhood education:

- Responds to and builds community support. In many communities, early childhood education initiatives now exist because of ballot measures that raised or allocated necessary revenue. Participatory planning can build coalitions needed to organize for passage, and, once passed, sustain support and involvement. Engaging families in early planning allows them to imagine what might be possible—and to help persuade elected officials to realize that vision.

- Increases accessibility and solutions that work for different families. Interested families cannot enroll in programs that won’t work for them, financially or logistically. Involving them in planning helps leaders design programs that families can actually use. Families have a range of views about what early childhood education should look like, often informed by cultural preference. Early childhood education is optional in most contexts—families won’t choose to participate unless they feel comfortable with the services being offered. Engaging them in the planning process helps design programs that better meet their needs.

- Addresses historical inequities. Early care and education has long been the work of women, and specifically women of color, who have long been excluded from policy conversations. This exclusion is reflected in many policies in the sector today. These include low wages for child care workers, with the lowest wages for women of color; policies that discriminate against home-based child care providers; and the ways in which some quality measurement tools direct resources away from certain types of providers in favor of others. Engaging child care providers and the families they serve in participatory planning can help correct some of these historic inequities.

In its study of over a decade of early education reform in three California communities, New America documented the role that collaboration, co-design, and participatory policymaking played in each community. The early childhood landscape in these communities and in California changed dramatically over 10 years—in part because community members helped drive local policy, and local leaders and practitioners were able to influence state policy. This shows the long-term impact of engaging communities in planning.

Many of the lessons learned in these three California communities are echoed by members of the Early Care and Education (ECE) Implementation Working Group. In Multnomah County, Oregon, the county gathered diverse stakeholders before an initiative even existed to collectively design a policy that could address local needs for early care and education, ultimately leading to the creation of the county’s Preschool for All program. In other communities, program leadership teams used participatory planning processes to support ongoing decision-making as programs matured. When New York City had to initiate new contracts with early childhood providers, city leaders embarked on a robust ‘listening tour’ to solicit feedback and draft a procurement based on the input. This required building trust with communities because prior procurements were largely developed behind closed doors.

Regardless of how and when participatory planning fits into a process, there are lessons to take from the communities in the working group. The variety of approaches underscores that there is no one “right” way to do it and that any process should be responsive to community context. There are procedural lessons about how policymakers can design planning processes that maximize impact and effectiveness. There is also a set of lessons for the deeper change work that government agencies will need to do to effectively engage in new ways that can feel very different from past efforts.

Lessons from the ECE Implementation Working Group

1. Engage communities from the start.

Communities lean into participatory planning at different stages in the implementation of early childhood programs. Some locations launched participatory planning processes before an early childhood program existed, inviting community members to participate in the process that ultimately led to a strategic plan, a ballot measure, and a way forward. Early adoption of participatory planning can create goodwill in the community for the work, help cultivate community champions, and design programs that are more responsive to community needs.

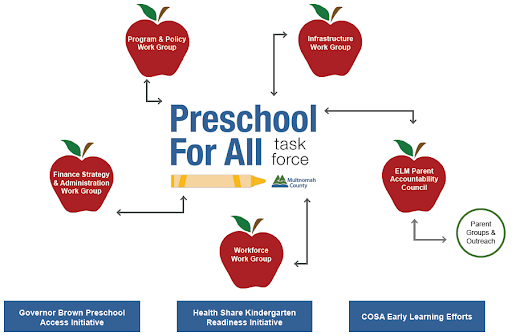

Multnomah County—recognized nationally for its approach—convened a task force with over 100 community members to work alongside technical experts. They met continuously for nine months, building on over a decade of foundational work led by communities and families. The task force had four workgroups focused on specific topics: policy and program; workforce; infrastructure; and finance, strategy, and administration. Each workgroup presented its recommendations back to the full task force and to a formal body known as the Early Learning Multnomah (ELM) Parent Accountability Council. The final roadmap included over 50 recommendations that served as the framework for Preschool for All.

Figure 1 | Engaging Parents and Experts in Multnomah County Pre-K Planning

Multnomah County’s Preschool for All Task Force included expert work groups and an explicit role for families.

Source: Courtesy of Multnomah County Dept. of County Human Services, used with permission.

Multnomah County continued to leverage diverse working groups as policymakers translated the initial roadmap into an implementation plan. Now that the Preschool for All program is up and running, the county has an Advisory Committee with very intentional representation from the early childhood workforce, underrepresented groups, and engaged community members.

In 2018, an Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, ballot measure that would have increased property taxes to support a range of child well-being programs narrowly failed. Because so many voters and community members had supported the design process—and had pushed for the measure at the ballot box—a new community task force came together to examine other pathways to address child care needs in the county. From this group’s work, a new county Department of Children Initiatives was born in 2021, which played a key role in expanding child care after the pandemic.

Not all municipal early childhood programs were initiated through a participatory process—some were developed through planning sessions with political staff and an inner circle of advisors. This does not necessarily make them inferior, but adopting participatory planning processes later will require a new mindset and some organizational change.

2. There won’t always be time for participatory planning. Make it anyway—or explain why you can’t.

Policymakers commonly cite time constraints to justify avoiding participatory planning. There are valid reasons why planning processes need to move fast; there may be external deadlines imposed by the budget or political process and windows of opportunity that policymakers cannot afford to miss.

In the long term, participatory planning can save time. Early stakeholder engagement can reduce pushback and smooth implementation. When timing comes up as a reason to bypass engagement work, policymakers should question which deadlines are fixed or flexible, self-imposed, or truly required. Some communities leaned into pilots—small-scale versions of new programs—as a way to test models and continue to solicit feedback before solidifying implementation plans. Leaders can also consider whether there might be less resource-intensive options for engagement; for example, by launching a survey to gather feedback if there is not time to plan and conduct in-person sessions.

Sometimes launching a new and participatory planning process is not feasible. Policymakers should be upfront with community members when there isn’t time for more engagement rather than just dodging the issue. When delivered transparently and sincerely, this information can even build trust with community members, as they come to see that program leaders themselves face many limits on authority and resources. The fact that there might not always be time underscores the importance of participatory planning wherever possible. If policymakers set a consistent pattern, community members may be more forgiving when there are exceptions.

Policymakers can also leverage previous work to gather community input. When Alameda County, California, passed the Children’s Health and Child Care Initiative for Alameda County (Measure C) in 2020, winning $150M in new revenue annually for children, the plan was largely based on previous planning work for a similar ballot measure that failed in 2018. Measure C passed as a community-led initiative, with the support and advocacy of many grassroots leaders.

Lastly, rapid implementation at a program’s outset can make room for participatory planning later on. When Pre-K for All launched in New York City, the team had less than two years to grow preschool capacity from 19,000 seats to a program serving 70,000 four-year-olds to meet the new mayor’s timeline. This limited time for engagement with child care providers and community members hurt trust amongst the sector. Three years later, the mayor announced the city’s preschool program would grow to serve three-year-olds. The political goodwill won with the fast pre-K launch helped the implementation team take a slower and more geographically focused approach to 3–K roll out. Instead of launching citywide, 3–K began in two communities, allowing the team to focus on engagement and relationship-building with local providers.

3. Invite more people to the table—and include more than just “the usual suspects.”

Engaging parents and educators matters, but neither group is a monolith, and the depth and diversity among them means that no one provider or parent can speak for everyone. Relying on a single representative can tokenize individuals and limit the quality of their input.

To expand the circle, policymakers will need to go beyond organized parent and provider groups. This should include engaging providers across different early childhood education settings and families with a range of needs, including non-English speakers and parents of children with disabilities. Multnomah County’s Parent Accountability Council names six specific cultural communities to be represented in the group’s membership.

Expanding engagement does not have to mean putting dozens of people onto an advisory group. Surveys, focus groups, or broader public forums are other mechanisms to collect input, and these broader mechanisms can open up opportunities to engage new constituents. The Cincinnati Preschool Program is required to perform an annual evaluation and has always opted to include survey feedback from parents and educators. In recent years, the team has also surveyed preschoolers themselves. Some critics said the children were too young to meaningfully contribute, but educators and caregivers championed the effort and found ways to incorporate their input. The information, which has now been included in three annual evaluations, provides added color on the program and helps policymakers understand what the program means to its participants.

Figure 2 | User Feedback from Cincinnati Preschool Program Students

Detail from the Cincinnati Preschool Promise annual evaluation showcases feedback from preschoolers. The first three items in the table about siblings were used to show preschoolers how to answer survey questions.

Source: Cincinnati Preschool Promise, “Evaluation Report: Cincinnati Preschool Promise’s Impacts in Early Childhood Education,” 2024, 44, https://issuu.com/promise2017/docs/cpp_year_7_full_evaluation_report_revised_09302024.

4. Give people support to meaningfully engage and meet them where they are.

Inviting people to the table is rarely enough. It is critical to offer tangible engagement support, particularly for community members with limited time and resources. Accessible program design starts with accessible research participation. This means public meetings that are accessible to people with disabilities, with translated printed materials and translation services, as well as child care, transportation, and food if in-person participation is required. Participants should have multiple pathways to engage, including in-person and virtual opportunities at different times of day, as well as the option to submit feedback asynchronously. The Cincinnati Preschool Program allows members of the public to share feedback in writing, but also through submitted video testimonials, drawings, and other media they felt comfortable sharing.

These kinds of support honor and value the time that communities commit. Some efforts have gone further, offering participants stipends, and, where possible, creating paid positions for engaged community members. When the Denver Preschool Program asks preschool providers to take surveys and provide input, the team builds out the survey instruments to avoid asking any questions they could easily verify themselves, such as the program’s address, and offers compensation for completing surveys.

Doing all of this work well takes real resources. In some municipalities, community philanthropy has stepped in to fund planning processes, particularly before new initiatives launch. Once a local program is funded, policymakers will need to consider what staff and other resources are needed to sustain participatory planning work.

5. Create leadership structures that include community members and mechanisms to hold the government accountable.

For community engagement to be more than just a box-checking exercise, it needs to be built into policymaking practice. In many communities, this has led to formal structures that give community members oversight on policy design and decision-making.

When New York City announced plans to expand free preschool to three-year-olds, city leaders convened an advisory group that included child care providers, advocates, parents, researchers, funders, and staff from other city and state agencies. This group offered advice about policy design, but their decision authority was limited. This structure was important but ultimately insufficient to really bring impacted groups into the policymaking process. Later on, New York City launched the Community Based Organization (CBO) Council—a forum for an elected group of CBO leaders to take on a formal shared leadership role. The child care program leaders represented on the council had access to confidential budgetary and enrollment data, and the advice and consent of the CBO Council became a required step for certain big decisions within the Department of Education.

The Cincinnati Preschool Promise is governed by a Board where parents and providers appoint a third of the members, guaranteeing that their voices are represented at the table. Further, a specific board committee focuses on gathering community input for all big decisions. The committee takes this charge very seriously, recently releasing commercials inviting members of the public to budget meetings.

In Alameda County, Measure C (the funding ballot measure described above) required the creation of an 11-member Community Advisory Council to develop recommendations regarding the program’s annual budget, quality improvement, community engagement initiatives, and technology use for program administration. The law specifies that the Council include two members of the early childhood workforce (one each from a center and home-based setting), two parents or guardians, and two administrators. With five members appointed to four-year terms by the Board of Supervisors and the others appointed by a representative county planning council, the architects of the revenue measure built in and funded substantive independent, community-led oversight and review of the program.

6. The biggest resistance may come from inside—it will take change management and thoughtful staffing to reverse this.

For teams unaccustomed to participatory planning work, there may be pushback. Team members (including leadership) may not see the value or feel it is worth the time. Some may see it as a box-checking exercise, not necessarily an opportunity for deep learning that will produce actionable results. Change management work may be required to reframe staff mindsets; this could include role modeling what good participatory planning looks like, providing evidence of the impact that good participatory planning can have, and giving team members the tools and resources to support their work.

When New York City launched an engagement campaign to gather input on a new early childhood procurement, every staff member in a managerial role was required to participate. All staff went through multiple training sessions to learn why the engagement process was so important and how to navigate difficult conversations. They also shadowed another team member more experienced with community engagement before leading a session themselves. Some staff members still questioned the value of engagement sessions, but over time this group became smaller and smaller.

It may also be necessary to “manage up” reluctant bureaucratic and political leadership, helping them understand both the value of gathering community input and, when necessary, using that input to course correct. This can be challenging when time investments in participatory planning (or its fruits) don’t align with program deadlines or goals. For example, Canada’s plan to offer child care to all families for $10 per day or less is extremely popular and successful, but providers and families pointed out that low teacher wages prevented expanding programs to meet demand. The national government and some provincial governments responded by adding funds to raise salaries, with the understanding that program growth may be slow until the pay increases are fully implemented.

While context is always key, there are a few rules of thumb for “managing up” in these situations.

- Ask questions to understand the reasons for urgency. Why does leadership want a particular change by a certain date? Is an election or key vote approaching, is the press paying special attention to the issue, or does leadership want to act fast just because they think the change will help people and want to get it moving?

- Try to address those reasons where possible. That does not necessarily mean just saying “yes!” It does mean framing the response in terms of those interests. Suppose leadership wants to expand in a particular community quickly because it needs those residents’ support for something critical, but implementation teams want more time to gather input. They can educate leadership on the ways that participatory planning can build support (or avoid backlash) or suggest something else that the team could do to build enthusiasm and support at the same time.

- Be as transparent as you can be with community members. Sometimes, the timeline is the timeline. These are moments when, to the extent possible, it is good to share transparently about the program’s actual constraints. And, if leadership is amenable, this can include time and space for community members to engage with leadership directly, so their perspectives are clearly articulated and understood.

What if, in your opinion, there is time for input, but leaders don’t make it a priority because they don’t think it is important? At such moments, allies outside the program can apply some respectful pressure on leadership to open up the process. These “inside-outside” strategies can be risky if leaders perceive them as disloyal, disruptive, or both, but they can be extremely effective when deployed with care and clarity.

7. Be genuine in requests for input, and demonstrate how that input will be used.

Many community members distrust engagement processes due to previous experiences: they were asked for feedback, took the time to provide it, and it was seemingly never acted upon. The onus is on policymakers to demonstrate how the input they are gathering is being used and set expectations about what impact community members will have on the ultimate outcome.

When New York City prepared to launch a new request for proposal (RFP) to expand the Pre-K for All program, the implementation team conducted a listening tour to gather stakeholder feedback. The process involved multiple rounds of conversation with as many of the city’s contracted providers as possible—more than 1,000 in total. In initial discussions, the team posed big questions and just listened. In subsequent conversations, the team shared the feedback collected to date and explained how it would be incorporated in planning. At the end of the process, the team synthesized the feedback that was not included in the final procurement and took the time to explain why. They also published a white paper—the RFP Preview—to outline the draft procurement and took additional written comments finally releasing the request for proposal. The final RFP included a companion document explaining what feedback had been incorporated from the written comments. All told, the timeline from launching the listening tour to sharing the RFP preview and releasing the final RFP was about one year.

Figure 3 | Participatory Planning in an Early Childhood Procurement

New York City took multiple steps to engage stakeholders in a procurement process, including one-on-one conversations, listening sessions, and public commenting.

Source: New America/Alex Briñas

When leaders are disingenuous about community engagement, the whole process can backfire. In one location represented in the ECE Implementation Working Group, new legislation called for a stakeholder group to give input on future preschool special education systems. However, the group was stacked with government officials and it became clear in meetings that community stakeholders were just along for the ride, with no plan to carry their ideas and feedback forward. When agency leaders presented the final plan to legislators, the stakeholders reported in a public hearing that their voices had been ignored. Soliciting input does not mean taking every suggestion wholesale, but disregarding the value of all community feedback harms the program by eroding organizational trust.

8. Sharing leadership may mean taking a step back.

Participatory planning requires sharing power. Policymakers may drive the process, but community members need to be more than just participants for their engagement to matter. In New Orleans, Agenda for Children (AFC) administered early childhood programs on behalf of the city for years. In 2013, they helped create the New Orleans Early Education Network, led by a Steering Committee of 22 early care and education stakeholders who represent publicly funded early learning programs, public administrators, parents, and community partners. When it came time to expand programs for children from birth to age three in 2018, the team understood that to plan the best program and earn necessary political support for funding, they would need to share power meaningfully. While AFC still leads the system, the Steering Committee gives significant direction to the effort. Over time, the Steering Committee grew to include additional stakeholder groups. By sharing power with these stakeholders, AFC created more collective power for the group.

Government leaders may need to accept they are not always the best positioned to engage community members. Trusted community leaders can be allies in this work. In Detroit, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation and the Kresge Foundation partnered with local leaders to start Hope Starts Here in 2016 to lay the groundwork for an early childhood development system. Hope Starts Here created a list of 216 Detroit organizations serving children and families. They invited organization members to listening sessions, but some responded with skepticism, hesitant to invite parents to meetings and distrustful about how their perspectives would be used. They proposed an alternative, offering to host the conversations themselves, collect the data, and synthesize it collaboratively. Together, Hope Starts Here and community partners trained 144 people to facilitate community conversations, holding 125 meetings in 45 days. Any organization could host a session as long as they followed the same general protocol. Over 18,000 people participated in the process, which led to the development of a six-part strategy. A different community partner led each pillar, with opportunities for parents and community members to continue organizing their neighbors in paid roles.

9. Truly engaging with community means allowing for outcomes that challenge assumptions and expectations.

True participatory planning may challenge policymakers’ assumptions about what outcomes might look like. Multnomah County launched its task force without preconceived notions of what would be in the final report. In developing the final recommendations, policymakers put equal value on the research of technical experts and the lived experience of parents and providers. There were times where community member experience was weighted more heavily than the technical research.

Harris County, Texas, is giving communities direct control over how new funds for early care and education will be used. Through the Early Learning Quality Networks initiative, four local organizations are convening stakeholders to assess child care quality across five targeted communities considered to be quality child care “deserts” and to develop quality action plans tailored to each community’s needs. The county will mobilize funds and resources to implement the quality action plans. Allowing communities the space to determine what good looks like on their own and empowering them to design the solutions—rather than carrying out “top down” government priorities—requires keeping an open mind and trusting that communities know what’s best for them.

Conclusion

Early childhood programs designed by the families they serve and the educators who make them possible will be stronger as a result. Participatory planning starts with good intentions that must be paired with effective process design and internal work to change hearts, minds, and behaviors. Lessons from cities and counties across the country offer suggestions about how to do this well. In each of these communities, leaders struggled to implement participatory planning at different moments. Their perseverance through those challenges, and the resulting programs and plans, illustrate why these processes can be so valuable.

Further Reading

Multnomah County documented detailed lessons from its planning process, as told in the words of 40+ people who participated:

- Multnomah County Preschool for All: Pathway to Success, a written report about lessons learned from the planning process; and

- A Pathway to Success: Developing the Preschool for All Policy, a visual study about community-based public policy.

The Children’s Funding Project recently released the Last Vote to First Dollar Toolkit to support implementation planning in communities that won funds at the ballot for children’s initiatives. The first chapter focuses on planning processes and community engagement. (Emmy Liss, co-author of this brief, is also a co-author of the Children’s Funding Project toolkit.)

Acknowledgments

Thank you to current and former members of the ECE Implementation Working Group for candidly sharing their experiences with participatory planning processes and their lessons learned. More information about the ECE Implementation Working Group is available here. In each of the communities highlighted in this brief, these processes were made possible through the labor and love of parents, educators, child care providers, and community members. This brief draws from their collective wisdom. The authors also extend their gratitude to former colleagues and community partners in New York City.