Higher Education Accreditation

Blog Post

March 1, 2013

A primer, overview and introduction to higher education accreditation.

Accreditation is the process of recognizing that an institution of higher education meets established standards, including a general standard of quality. In the United States, non-governmental organizations recognized by the Secretary of Education conduct the peer-review accreditation process for colleges and universities and their programs.

This overview provides a history of higher education accreditation; discusses the values and beliefs that underlie accreditation; describes the process of accreditation and types of accreditors; and reviews current and emerging issues in accreditation.

A Short History of Accreditation

As the number of educational institutions grew in the 1800s, it became increasingly difficult to distinguish between secondary schools, colleges and their respective educational offerings. At that time, there was little government oversight of higher education, so colleges and universities took it upon themselves to create voluntary, non-governmental organizations to provide standards to distinguish them from secondary schools. The first of these organizations was the New England Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools (now called the New England Association of Schools and Colleges), which was founded in 1885. By 1923, with the founding of the Western Association, the nation was fully covered by six regional accreditors, each tasked with accrediting colleges and universities in its respective region.

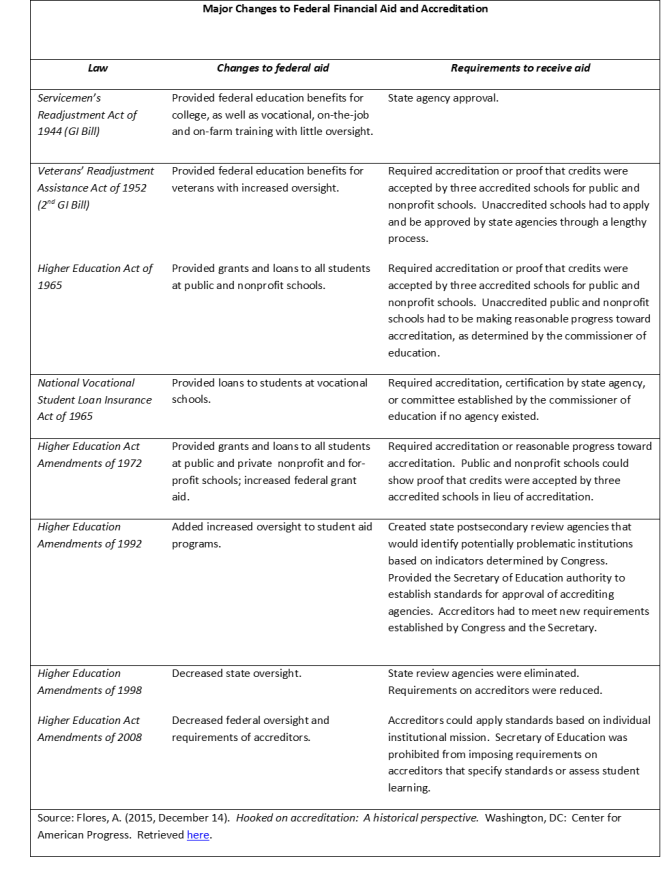

Although higher education accreditation has existed since the late 1800s, the federal government had little interest in the process until the early 1950s when federal investments in postsecondary education dramatically increased. Beginning with the passage of the Veterans’ Readjustment Act of 1952 (also known as the Korean GI Bill), Congress determined that it needed a system to ensure a basic level of quality for institutions receiving federal dollars, one that could prevent federal funds from going to poor quality, fly-by-night providers of higher education. To meet this need, the federal government turned to the existing system of accreditation – one that is private and voluntary. Using a non-governmental private actor to conduct institutional assessments avoided the need for the government to oversee and judge the quality of institutions directly.

Under the Veterans’ Readjustment Act of 1952, the U.S. Commissioner of Education was authorized “to publish a list of nationally recognized accrediting agencies and associations which he determines to be reliable authority as to the quality of training offered by an educational institution…”[i] This list was used by state approval agencies to determine the schools at which veterans could use their GI education benefits. When the federal government began providing financial support for college to students beyond veterans, Congress continued to rely on accreditation as a basic quality check for receipt of federal funds.[ii]

With passage of the Higher Education Act of 1965, Congress deemed as eligible for federal funding an institution of higher education that was “accredited by a nationally recognized accrediting agency or association or, if not so accredited, is an institution whose credits are accepted, on transfer, by not less than three institutions which are so accredited, for credit on the same basis as if transferred from an institution so accredited.”[iii],[iv] Carrying this accreditation eligibility criterion into subsequent reauthorizations of the Higher Education Act, Congress cast the voluntary system of accreditation into the role of primary gatekeeper for federal higher education funds. Although Congress has added additional institutional eligibility criteria over the years (e.g., standards for fiscal responsibility, cohort loan default rates) accreditation remains the key eligibility criterion for access to federal student loans and grants under Title IV of the Higher Education Act.

Values and Purposes of Accreditation

Values and Purposes of Accreditation

To understand the system of higher education accreditation in the United States it is important to appreciate the values and beliefs that underlie it. According to the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA)[i], the primary association and advocate for higher education accreditation and quality assurance in the United States, there are five core values of the American accreditation system:

- Institutions of higher education, not government, should be the primary authority on matters of academics and have primary responsibility for ensuring the quality of their academic programs.

- An institution’s mission is central to judging the quality of its academic program.

- To maintain and improve academic quality, institutional autonomy is paramount.

- The American system of higher education has grown and thrived due to the decentralization and diversity of the system.

- Academic freedom thrives under the academic leadership of institutions of higher education.[ii]

As the foundation for the modern day system of accreditation, accrediting agencies and associations have developed criteria and standards based on these core values that their member institutions must meet to become and remain accredited.

From these core values also flow the purposes and uses of accreditation. The system of accreditation purports to perform a variety of functions, including:

- Verifying to students and the public that an institution meets a set of established standards (e.g., curriculum, faculty, student services, fiscal stability) and assisting individuals in identifying the institutions that meet the standards.

- Determining eligibility for federal and state funds for higher education.

- Establishing criteria for professional and state certification and licensure.

- Assisting institutions in making determinations in accepting academic credits upon transfer from other institutions.

- Assisting employers in evaluating the academic credentials of prospective employees.

- Providing the public and the private sector with a basis for making determinations about private and public giving.

- Providing goals for institutional self-improvement and providing a means for involving faculty and administration in institutional evaluation, planning, and improvement.[iii]

The National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity

Although the federal government does not accredit institutions of higher education directly, it approves accrediting agencies that it deems to be “reliable authorities” with regard to the quality of the education or training provided by the institutions that they accredit. In 1968, the Commissioner of Education created the Accreditation and Institutional Eligibility Advisory Committee to assist the federal government in developing criteria to review and designate accrediting agencies under the Higher Education Act.

Today, this advisory committee is known as the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Integrity (NACIQI). It is an independent advisory committee established by statute that advises the U.S. Secretary of Education on the recognition of postsecondary accreditation organizations.

The functions and mission of NACIQI are laid out in Section 114 of the Higher Education Act. Specifically, NACIQI is to advise the Secretary of Education regarding:

- The establishment and enforcement of the standards for accrediting agencies under the Higher Education Act.

- The recognition of specific accrediting agencies or associations.

- The eligibility requirements for institutions of higher education under Title IV of the Higher Education Act.

- Recommendations for improvement of the eligibility and certification process for institutions of higher education.

- The relationships among accrediting agencies, states, and the federal government, commonly referred to as the higher education triad.

Over the years, Congress has stipulated specific standards in statute that NACIQI and the U.S. Department of Education must use to determine whether to recognize an accrediting agency as a reliable authority of the quality of the education or training provided by the institutions or programs it accredits. In addition to specifying that accrediting agencies must have standards related to student achievement, faculty, finances, and facilities, the Higher Education Act lays out required procedures for operations and the affording of due process to accreditors’ member institutions.

One of NACIQI’s functions is to put forth policy recommendations related to the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. NACIQI provided its most recent recommendations in 2015.

NACIQI consists of eighteen members, with six each appointed by the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, the President pro tempore of the U.S. Senate, and the U.S. Secretary of Education. As is required by statute, NACIQI meets not less than two times per year. Meetings are typically held in the spring and the fall and are open to the public.

In addition to accreditors receiving recognition from the U.S. Department of Education and NACIQI, the private, non-government Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA) also reviews and recognizes accreditors. Though many accreditors are recognized by both the U.S. Department of Education and CHEA, for purposes of federal student financial aid, it is only recognition by the U.S. Department of Education that counts.

The Accreditation Process

At the core of the accreditation process are the standards. As accreditation is a voluntary, member-driven process, the standards for accreditation are developed and established in collaboration between the accreditors and their member institutions. In becoming accredited, an institution agrees to submit to the standards of its accreditor. Although standards are established and agreed to by accreditors and their member institutions, the U.S. Department of Education requires its recognized accreditors to assess various elements stipulated by Congress. The required standards assess an institution’s:

- (A) Success with respect to student achievement in relation to the institution’s mission, which may include different standards for different institutions or programs, as established by the institution, including, as appropriate, consideration of state licensing examinations, consideration of course completion, and job placement rates;

- (B) Curricula;

- (C) Faculty;

- (D) Facilities, equipment, and supplies;

- (E) Fiscal and administrative capacity as appropriate to the specified scale of operations;

- (F) Student support services;

- (G) Recruiting and admissions practices, academic calendars, catalogs, publications, grading, and advertising;

- (H) Measures of program length and the objectives of the degrees or credentials offered;

- (I) Record of student complaints received by, or available to, the agency or association; and

- (J) Record of compliance with program responsibilities under Title IV of the Higher Education Act based on the most recent student loan default rate data provided by the Secretary, the results of financial and compliance audits, program reviews, and any such other information as the Secretary may provide to the agency or association.[iv]

Additionally, for institutions offering distance or correspondence education, the Higher Education Act requires that accreditors have standards for institutions to verify that the student who enrolls for a course is the same student who completes and receives credit for the course. [v]

After receiving initial accreditation, institutions must be reevaluated for reaccreditation at least every ten years based upon their accreditor and the type of accreditation. Additionally, over the course of an institution’s accreditation, accreditors continually monitor their member institutions.

As membership organizations, the activities of accrediting agencies are financed through annual membership dues paid by member institutions as well as through fees assessed on institutions for the cost of the accreditation review.

Evaluation

According to CHEA, the key components to the accreditation evaluation process are:

- Self-Study: Institutions conduct an in-depth self-study that measures and evaluates their performance based on the standards of their accreditor.

- Peer-Review: The review and evaluation of an institution is conducted primarily by a team of faculty and administrative peers. Volunteer institutional peers review the institution’s self-study and serve as members of the on-site evaluation team.

- Site Evaluation: A team of peer volunteers and members of the public visits the institution to meet with various members of the institutional community to verify in person that the institution meets the standards for accreditation.

- Judgment by Agency: Following the review of the self-study and the site visit, the accreditation team makes a recommendation to the accrediting agency. The accrediting agency then makes an accreditation determination. Those judgments may include a variety of determinations – initial accreditation granted, initial accreditation denied, accreditation continued, institution placed on notice or warning, institution placed on probation, accreditation terminated or denied.

- Periodic Review and Monitoring: Following initial granting of accreditation and following granting of reaccreditation, the accrediting agency continually monitors its institutions. [vi]

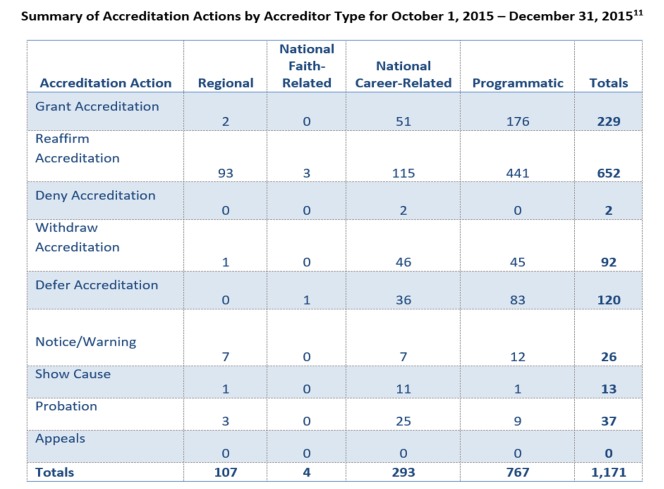

Below is a quarterly snapshot of accreditation judgments made by accrediting agencies in the first quarter of 2015.

It is well accepted that the loss of accreditation is more than just a loss of a simple designation. Because institutions rely on federal funds from student financial aid, in the overwhelming majority of cases, an institution’s loss of accreditation would result in its forced closure. Recognizing this, accreditors rarely remove a member institution’s accreditation. Policymakers, also understanding the repercussions of the loss of accreditation, have built into law a series of due process requirements that accreditors must afford an institution prior to stripping their accreditation. Often these measures result in years of delay in administrative action.

Types of Accreditors

Over the years, two types of accreditors have evolved – institutional accreditors and specialized/programmatic accreditors. Institutional accreditors evaluate institutions as a whole, determining, among other things, if an institution has adequate administrative, fiscal, and human capacity to carry out its mission and goals. While an institution’s offerings in and oversight of its individual departments and schools are reviewed during the course of institutional accreditation, such academic departments and schools are not individually or separately reviewed.

Specialized or programmatic accreditors, on the other hand, evaluate a particular school, department, or program typically related to a given profession or vocation, e.g., medicine, law, funeral services, massage therapy. Although a number of states require students to graduate from an accredited specialized program for licensing purposes (e.g., medical school), for purposes of Title IV eligibility under the Higher Education Act, it is institutional accreditation that is the key.

Institutional Accreditors

There are two types of institutional accrediting agencies in the United States – regional accreditors and national institutional accreditors. Regional accreditors primarily accredit public and private nonprofit degree-granting institutions, though they do accredit for-profit institutions as well. Among the national institutional accreditors there are two broad types: (1) national career-related accreditors, which mainly accredit for-profit career colleges and non-degree granting institutions, and (2) national faith-related accreditors, which mainly accredit nonprofit religious and doctrinally-based institutions.

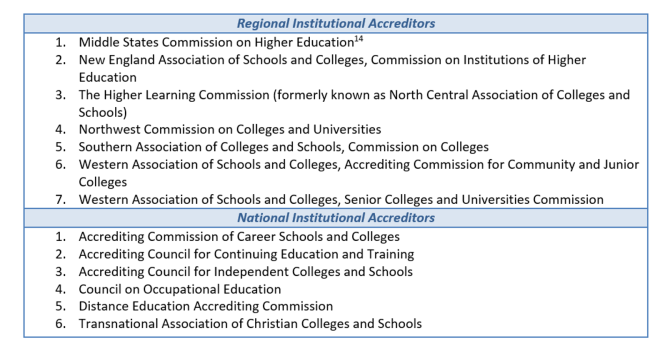

Currently, there are seven regional accrediting agencies and six national institutional accreditors. In addition to the regional accreditors, the New York Board of Regents is authorized under the Higher Education Act to serve as an institutional accreditor for Title IV purposes, the only such state government agency authorized under law to serve in this capacity. With regard to degree-granting institutions, the following accreditors are recognized by the U.S. Department of Education.[i]:

More detailed information on the scope of recognition for each of the recognized institutional accreditors can be found here.

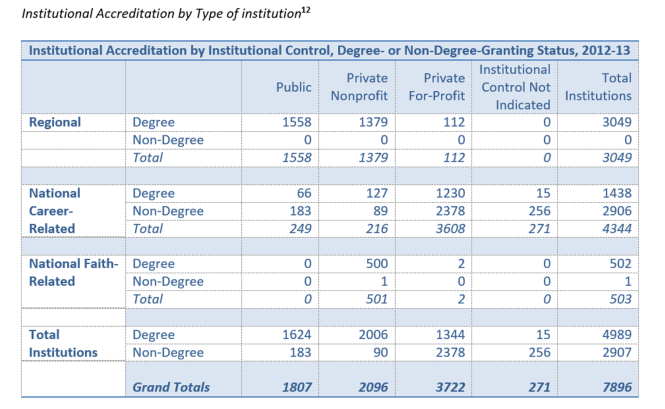

Institutional Accreditors, Institutions, and Students

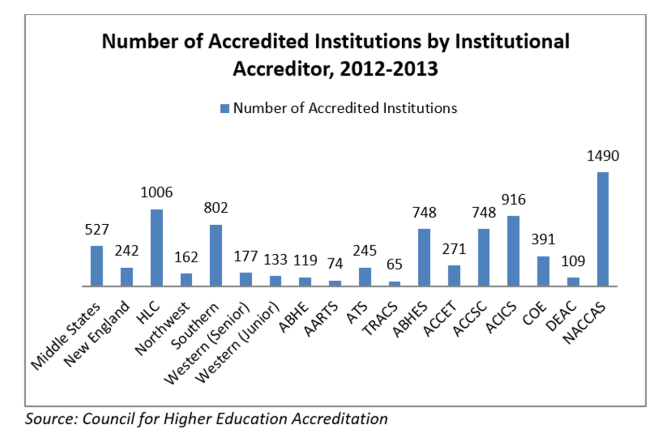

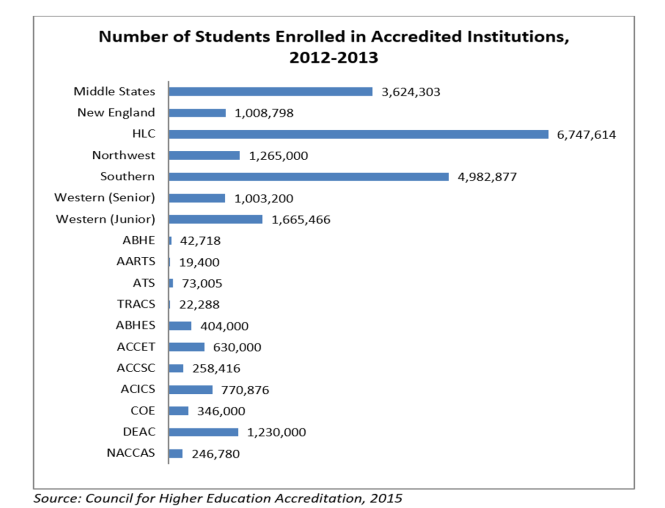

In 2012-2013, 7,896 institutions of higher education were accredited. Regional accreditors accredited 3,049 institutions and national accreditors accredited 4,847 institutions. More institutions are accredited by national accreditors than regional accreditors, but more students attend schools accredited by regional accreditors. Of the almost 24 million students enrolled in accredited institutions in 2012-2013, 20.3 million were in schools with regional accreditation.[i] The following charts provide information on the number of institutions accredited by each of the institutional accreditors and the number of students enrolled in those institutions.

Specialized/Programmatic Accreditors

Specialized or programmatic accreditors evaluate a particular school, department, or program typically related to a given profession or vocation. Specialized accreditors span a variety of fields from education, to the arts and humanities (e.g., art, music, theater, dance), to personal services such as massage therapy, to a number of health care related vocations (e.g., nursing, physical therapy, medicine).

For purposes of eligibility for Title IV grants and loans, only institutional accreditation is required. However, a programmatic accreditor may also serve as an institutional accreditor in the case of a specialized or vocational institution that is freestanding and whose operations are wholly separate and independent from any other accredited institution with a broader educational mission and offerings.

In addition to recognizing accreditors for purposes of Title IV of the Higher Education Act, the U.S. Department of Education also recognizes programmatic/specialized accrediting agencies for the purpose of participation in programs administered by other federal agencies.[i] For example, to participate in certain loan programs administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, participants must have graduated from a veterinary school accredited by the American Veterinary Medical Association.

The U.S. Department of Education lists currently recognized specialized/programmatic accreditors here.

Most accreditors are recognized by both the U.S. Department of Education and by the Council for Higher Education Accreditation (CHEA). However, an accreditor seeking recognition from the Secretary of Education must meet the Department’s regulatory criteria for the recognition of accreditors, and must have a link to a federal program (e.g., federal student aid).[ii] Thus, some programmatic accreditors, like the Accreditation Council for Business Schools and the American Library Association Committee on Accreditation, cannot be recognized by the U.S. Department of Education and are recognized solely by CHEA.[iii]

Concerns and Recommendations for Reform

The federal government’s investment in student aid is significant at more than $160 billion in fiscal year 2015[iv]. Given this, policymakers and others are asking what students, the government, and taxpayers are getting for such a large investment. Although many indicators point to the United States still being a leader in higher education research and innovation, some paint a less than stellar picture of performance. Annual government statistics[v] indicate that less than 60 percent of students who start a bachelor’s degree program complete a degree within six years, and, for low-income, minority, and non-traditional students these six-year completion rates are even lower. Additional surveys and studies also indicate that in many instances students learn very little while they are in college[vi].

There has been growing concern about what accreditation is doing to ensure academic quality, especially given its role as the gatekeeper for the federal student aid system. Coupled with this concern is the changing postsecondary landscape, with a surging number of non-institutional providers, such as coding boot camps, MOOCs and competency-based education courses. This new landscape suggests new roles for quality assurance or accreditation organizations.

Several reports have been released to address the concerns about student performance and the changing postsecondary landscape. In April 2012 NACIQI, at the behest of the Secretary of Education, released a report entitled Higher Education Act Reauthorization: Accreditation Policy Recommendations to provide recommendations for reform, including retaining the linkage between accreditation and eligibility for federal student aid funds and clarifying the roles of each member of the triad.[vii] In 2014, a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report raised concerns about the Department’s oversight of schools and accreditors. In 2015, in an effort to extend its formal policy agenda, NACIQI issued recommendations to build upon its 2012 report. The recommendations suggest simplifying the accreditation and recognition process; enhancing nuance in that process; reconsidering the relationship between quality assurance processes and access to Title IV funds; and reconsidering the roles and functions of NACIQI itself.

More recently, in late 2015 and early 2016, the U.S. Department of Education put forth a “transparency agenda” for accreditation. The Department’s website publishes accreditors’ standards for evaluating student outcomes and key student and institutional metrics for each accreditor. In addition, the Department launched the Educational Quality through Innovative Partnerships (EQUIP) experimental site designed to “evaluate the effectiveness of granting title IV student aid flexibility to partnerships between innovative postsecondary institutions and non-traditional providers.”[viii]

Among the many suggestions for accreditation reform that have come from researchers, policy advocates and institutions are:

- Severing the link between accreditation and eligibility for federal student aid. Some have argued that the only way for accreditation to serve as a real means for quality control and improvement is to sever the tie between accreditation and eligibility for Title IV funds.[ix] Others oppose severing the Accreditation-Title IV tie, fearing what system the federal government might put in its place as a quality gatekeeper for federal funds.

- Increasing transparency. For most of its history, accreditation has been a process carried out primarily behind the scenes, with little transparency and public understanding. While some accreditors have begun posting accreditation decisions on their websites, there continues to be room for improvement.[x]

- Redesigning the peer-review model of accreditation. Over the years many have argued that the peer-review model and membership-driven basis of accreditation in the United States is rife with conflicts of interest thus stymieing any true quality control efforts.

- Creating a differentiated accreditation system. Some have advocated for a more nuanced system of accreditation with determinations that go beyond the current pass-fail system. Such a system could include more risk-sensitive accreditation reviews that concentrate more attention and monitoring resources on weaker institutions.

- Reforming data collection. Many advocate for the collection of better data on educational outcomes. Accreditation terminology could also be further streamlined to use a common vocabulary to describe accreditation actions and terms.[xi]

- Defining new accreditors. Some have called for the creation of entirely new accreditation options and allowances for new modes of instructional delivery (e.g., CBE and MOOCs).

How many of these recommendations for improvement will be made to the current system of accreditation remains to be seen. Any changes to federal law and accreditation are most likely to be made during the next reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, which was scheduled for reauthorization in 2013. In the absence of renewal, changes to accreditation can still occur outside of federal statute. For example, accreditors’ decisions to post institutional reports or decisions on their websites was unrelated to statutory change. Also, the Department is carrying out EQUIP experiment sites pilot within its current statutory authority.

[i] Section 496(a)(2) of the Higher Education Act.

[ii] For further explanation of the ED recognition process, see http://www2.ed.gov/admins/finaid/accred/accreditation_pg3.html#Recognition.

[iii] A directory of all CHEA recognized accreditors may be accessed at: http://www.chea.org/pdf/CHEA_USDE_AllAccred.pdf

[iv] Retrieved from http://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/trends-student-aid-web-final-508-2.pdf (pages 12-13).

[v] Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=40

[vi] See for example Richard Arum and Josipa Roksa, Academically Adrift (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011) and Mark Kutner, Elizabeth Greenberg, and Justin Baer, A First Look at the Literacy of America’s Adults in the 21st Century (Jessup, MD: National Center for Education Statistics, 2005) http://nces.ed.gov/NAAL/PDF/2006470.PDF.

[vii]Report to the U.S. Secretary of Education: Higher Education Act Reauthorization Accreditation policy Recommendations by the National Advisory Committee on Institutional Quality and Improvement Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/naciqi-dir/2012-spring/teleconference-2012/naciqi-final-report.pdf.

[viii] For more information about EQUIP, see http://www.whiteboardadvisors.com/files/WBA-ESI%20EQUIP%20POLICY%20BRIEF-FINAL.pdf.

[ix] See Alternative to the NACIQI Draft Final Report by Anne Neal and Arthur Rothkopf. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/naciqi-dir/2012-spring/teleconference-2012/naciqi-final-report.pdf.

[x]One accreditation agency, the Western Association of Schools and Colleges’ Senior Colleges and University Commission, publishes detailed information about its member institutions’ accreditation decisions in an online database. See http://www.wascsenior.org/institutions

[xi] In 2012, ACE encouraged accreditors to use common terminology. See http://www.acenet.edu/news-room/Documents/Accreditation-TaskForce-revised-070512.pdf. Also, in 2014, Regional accreditors adopted common terms. See http://www.aacrao.org/resources/resources-detail-view/regional-accreditors-adopt-common-terms.

[i] See p. 3 of http://www.chea.org/pdf/Overview%20of%20US%20Accreditation%202015.pdf

[i] Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/admins/finaid/accred/accreditation_pg6.html

[i] CHEA was formed in 1996 by college and university presidents to “serve students and their families, colleges and universities, sponsoring bodies, governments, and employers by promoting academic quality through formal recognition of higher education accreditation bodies” and to “coordinate and work to advance self-regulation through accreditation.”

[ii] Adopted from An Overview of U.S. Accreditation by Judith Eaton, The Council for Higher Education Accreditation. Retrieved from http://www.chea.org/pdf/Overview%20of%20US%20Accreditation%202012.pdf and Accreditation and Recognition in the United States by Judith Eaton. Retrieved from: http://www.chea.org/pdf/AccredRecogUS_2012.pdf .

[iii] Adopted from An Overview of U.S. Accreditation by Judith Eaton, The Council for Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.chea.org/pdf/Overview%20of%20US%20Accreditation%202012.pdf & The U.S. Department of Education, College Accreditation in the United States. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/admins/finaid/accred/index.html.

[iv] Section 496(a)(5) of the Higher Education Act.

[v] Section 496(a)(4) of the Higher Education Act.

[vi] See Eaton, J. (2015, November). An Overview of U.S. Accreditation. Washington, DC: CHEA. Retrieved from http://www.chea.org/pdf/Overview%20of%20US%20Accreditation%202015.pdf

[i] Veterans’ Readjustment Act of 1952, Pub. L. No. 82-550, §253.

[ii] The National Defense Education Act of 1958, Pub. L. No. 85-864, often considered the predecessor to the Higher Education Act of 1965, was the first federal statute to provide financial support beyond veterans to attend higher education.

[iii] Higher Education Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 89-329, §801.

[iv] The provision allowing an unaccredited institution whose credits were accepted for transfer by at least three accredited institutions to be eligible was dropped in the 1992 reauthorization of the Higher Education Act. However, there are allowances in the statute that allow for new institutions with provisional accreditation from a recognized accrediting agency to qualify for Title IV student aid.

<h1>block-block-53 {</h1> <p>display:none; }</p> <h1>block-block-16 {</h1> <p>display:none; }