Federal Tax benefits for HIgher Education

A Background Primer

Blog Post

April 17, 2015

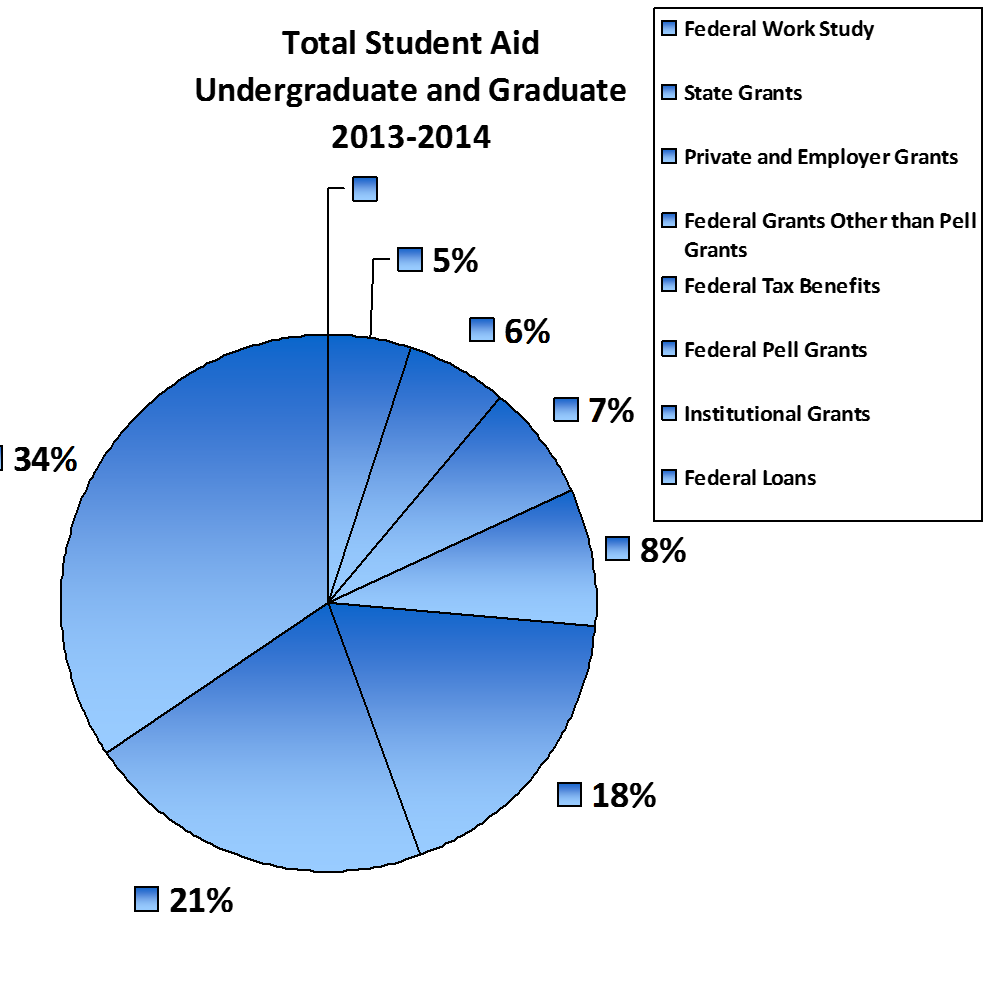

The federal government provides financial assistance for higher education in four broad categories – grants, work study, loans and tax benefits. For the majority of the last fifty years, and ever since the federal government first began providing financial assistance for higher education in the 1950s, the dominant forms of aid have been grants, work study assistance and loans.

Source: Trends in Student Aid 2014

Since the mid-1990s, however, federal income tax benefits have increasingly become a part of the student financial aid landscape. Over the last decade, federal expenditures (foregone tax revenue) in the form of higher education tax benefits have increased 109 percent. In 2013-2014, federal education tax benefits made up eight percent of total student aid (federal, state, institutional, private) for postsecondary education. Looking only at federal student aid in 2013-2014, education tax benefits constituted $18.7 billion, or 11 percent, of the $164.5 billion in financial assistance.The number of students and families receiving tax benefits for postsecondary education was 13.8 million in 2013-2014, making this category of federal financial aid assistance the most utilized of all federal financial aid programs. Though they are the most used form of federal financial aid, federal education tax benefits represent the smallest average amount of aid per individual with an average benefit of $1,330.

Source: Trends in Student Aid 2014

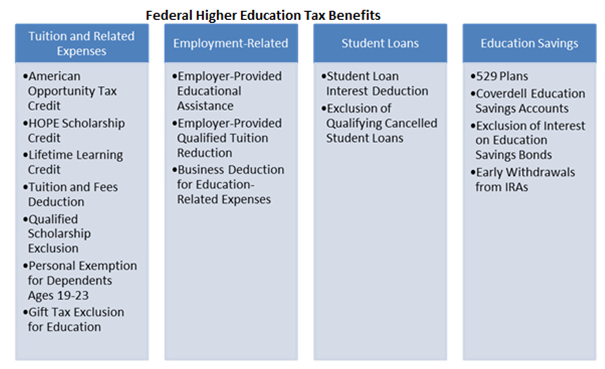

Types of Federal Higher Education Benefits

Generally speaking, the Internal Revenue Code provides four categories of tax benefits – credits, deductions, exemptions and exclusions. These benefits may either reduce an individual’s tax liability (i.e., the amount of taxes an individual owes) or reduce the amount of an individual’s income that is subject to taxation.

• Tax Credit: Tax credits reduce the amount of tax a tax filer owes on a dollar-for-dollar basis. A tax credit may be either nonrefundable or refundable. A nonrefundable credit can only reduce a tax filer’s tax bill to $0 and cannot produce a tax refund where one did not already exist. A refundable tax credit, on the other hand, can exceed taxes owed and can result in a tax refund.

• Tax Deduction: Tax deductions reduce the amount of a tax filer’s income that is subject to taxation. The eligible tax deduction amount is the amount of reduction to a taxpayer’s taxable income. If an individual is eligible for a $2,000 tax deduction and his or her taxable income is $50,000 prior to taking the deduction, the individual’s taxable income after taking the deduction would be $48,000.

• Tax Exemption: Tax exemptions work in the same way as do tax deductions in reducing an individual’s taxable income. The most common tax exemptions are the personal and dependent exemptions. Tax filers may claim a personal exemption for themselves and any dependents they support. The personal exemption for tax year 2014 is $3,950.

• Tax Exclusion: The Internal Revenue Code contains a number of provisions that explicitly exclude certain types of income or amounts of income from taxation. These types of income are not included as taxable income.

Over the years, Congress has enacted a number of tax benefits to assist individuals and families pay for college. These higher education tax benefits come in all types – credits, deductions, exemptions, and exclusions – and may broadly be divided into four categories: tax benefits for tuition and related expenses, employment-related higher education tax benefits, tax benefits for student loans and tax benefits for education savings.

Many of these higher education tax benefits have been part of the Internal Revenue Code for several decades and some date back to the 1950s. Yet, prior to enactment of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-34), tax benefits for higher education remained a relatively small part of the federal financial aid picture. Prior to the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, Congress enacted the following tax benefits for higher education:

• Personal Exemption for Dependents Ages 19-23

• Qualified Scholarship Exclusion

• Gift Tax Exclusion for Education

• Employer-Provided Educational Assistance

• Employer-Provided Qualified Tuition Reduction

• Business Deduction for Education-Related Expenses

• Student Loan Interest Deduction

• Exclusion of Qualifying Cancelled Student Loans

• 529 Plans

• Exclusion of Interest on Education Savings Bonds

When President Clinton announced his Administration’s proposal for providing middle class families with tax credits to pay for college in 1996, using the Internal Revenue Code to help families meet their financial obligations to postsecondary education took hold. Middle class families who felt they were being priced out of college, but who did not qualify for Pell or subsidized loans, finally felt as if they were getting a “break” they deserved.

Signed into law in 1997, the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-34) created four additional higher education tax benefits and reinstated the student loan interest deduction which had been eliminated from the tax code as part of the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (P.L. 99-514). The tax benefits in the 1997 Taxpayer Relief Act were:

• Hope Scholarship Credit

• Lifetime Learning Credit

• Student Loan Interest Deduction

• Coverdell Education Savings Accounts

• Cancellations of the Penalty for Early Withdrawals from Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs)

In 2001, as part of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Act of 2001 (P.L. 107-16), Congress added two new tax benefits – the tuition and fees deduction and tax-free distributions from 529 college savings plans. Then, as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (P.L. 111-5), Congress temporarily replaced the Hope Scholarship Credit with the more generous American Opportunity Tax Credit. In 2012, lawmakers extended that change through tax year 2017 under the American Taxpayer Relief Act (P.L. 112-240).

Most of these tax benefits have provisions that disallow tax filers from using the same qualified educational expense to claim more than one tax benefit. Because many tax filers may meet the qualifications for more than one tax benefit, individuals must examine each benefit separately to determine which offers the greatest financial benefit.

Current Considerations and Issues

Since enactment of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (P.L. 107-16), and the introduction of higher education tax credits, the popularity of using the Internal Revenue Code as a means of offering students and families, especially middle class families, financial aid to pay for college has grown. While popular, a number of reports have indicated that the sheer number of benefits and complex eligibility rules often make it difficult for families to understand the tax benefits for which they may be eligible and choose the tax benefit that is most financially beneficial to them.

A 2012 report issued by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that in tax year 2009 almost 14 percent of filers failed to claim a higher education credit or deduction for which they were eligible.[1] That same GAO report lays out a number of possible reasons for families either failing to claim a benefit for which they are eligible or for making a suboptimal choice (i.e., choosing a less financially beneficial option) in their selection of education tax benefits. These reasons include lack of awareness or misunderstanding of eligibility, confusion over the sheer number of provisions, similarity in provisions making it difficult to determine which one may be best, and differences in key definitions such as the multiple definitions for qualified education expenses.

Growth in the uptake of these tax credits and deductions was relatively flat for the first part of the decade but their popularity and uptake have more than doubled in the past five years. This uptick was caused almost exclusively by the introduction of the more generous American Opportunity Tax Credit in 2009. In 2012, 11.1 million tax filers benefited from an education tax credit and 1.3 million tax filers benefited from an education tax deduction for a total of $17.4 billion in tax savings.

At a time of budget constraints, some have questioned whether spending on tax benefits might better be directed towards traditional financial aid programs – Pell, loans, work study, etc., especially those traditional programs that are more targeted to lower-income families and students. In 2012, 57 percent of higher education tax benefits went to families with adjusted gross incomes above $50,000, with 25 percent going to families with adjusted gross incomes above $100,000. Additionally, for both the credits and the deduction, the average tax savings per recipient is greater for both middle and upper-income families.

A final set of considerations related to higher education tax benefits concerns their effectiveness in meeting public policy goals. A recent GAO report in response to Congressional inquiries on the effectiveness of both Title IV and federal higher education tax benefits found that research into the effects of these programs on college attendance, choice, cost, persistence, and completion is scant and questions of effectiveness remain largely unanswered.[2] As Congress takes up comprehensive tax reform and the reauthorization of the Higher Education Act for consideration, questions related to the purposes, target populations, and effectiveness of all forms of federal financial assistance for higher education – education tax benefits and traditional Title IV aid – may be in order.

Details of Federal Higher Education Tax Benefits

American Opportunity Tax Credit and Hope Scholarship Credit (IRC Sec. 25A)

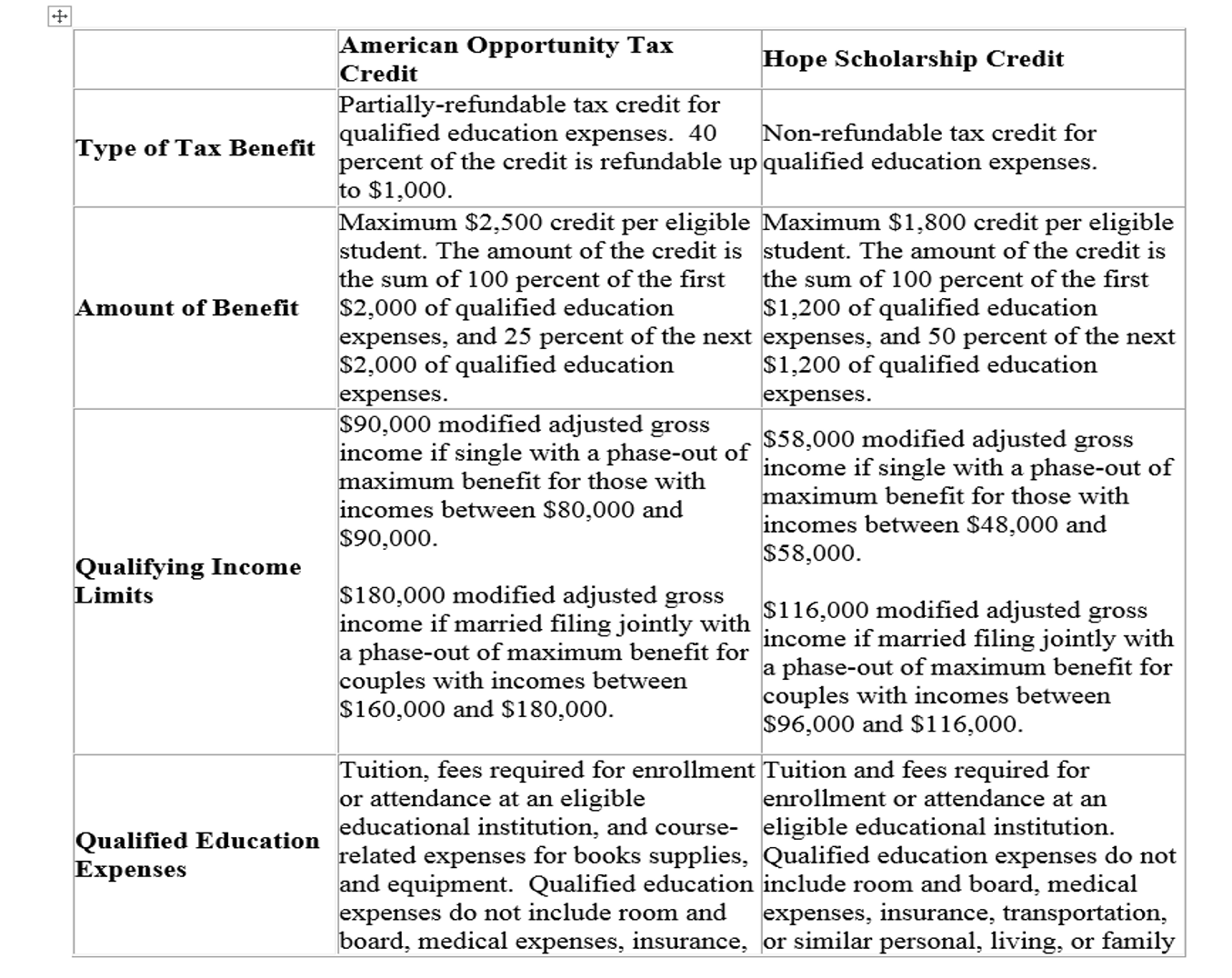

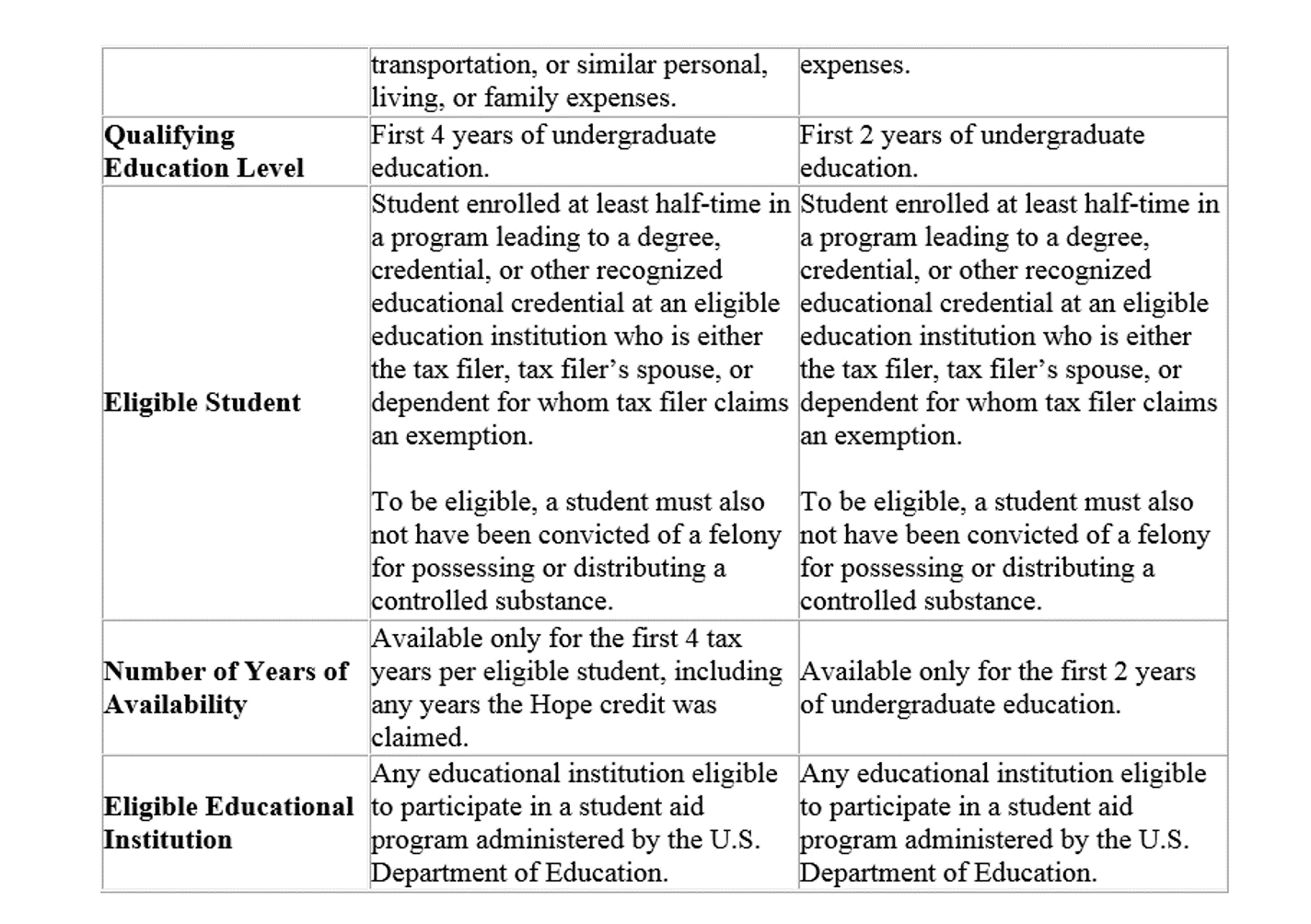

Both the American Opportunity Tax Credit (AOTC) and the Hope Scholarship Credit are for undergraduate education. The AOTC has temporarily replaced the Hope Credit, and barring further Congressional action, the AOTC is set to expire at the end of tax year 2017. After such time, the Hope Credit is scheduled to come back into effect.

As mentioned earlier, the AOTC is a more generous version of the original Hope Scholarship Credit. In addition to the AOTC providing a higher maximum benefit than Hope, the AOTC covers four years of college as opposed to two, has higher income phase-out limits, and has a broader definition of qualified education expenses. The AOTC is also a partially refundable credit. Thus, under the non-refundable Hope, if a tax filer has $0 tax liability, the tax filer receives no financial benefit. However, under AOTC, which is partially refundable, a tax filer with $0 tax liability may still receive a financial benefit of up to $1,000.

Details of the features of the American Opportunity Tax Credit and the Hope Scholarship Credit in its last operational tax year 2008 follow.

Lifetime Leaning Credit (IRC Sec. 25A)

Unlike the American Opportunity Tax Credit and the Hope Credit which are both for undergraduate education exclusively, the Lifetime Learning Credit may be used for undergraduate or graduate education. Additionally, while a student must be enrolled on at least a half-time basis and in a program leading to a degree or credential to qualify for the AOTC or Hope, to claim the Lifetime Learning Credit a student need only enroll in one or more classes that may or may not lead to a degree or credential.

Tuition and Fees Deduction (IRC Sec. 222)

In 2001, Congress created a third tax benefit to assist families and students cover the cost of college. Similar to the Lifetime Learning Credit, the Tuition and Fees deduction covers both undergraduate and graduate education and may be used for one or more classes. Congress has typically only enacted the deduction on a temporary basis. The deduction was most recently extended for the 2014 tax filing season.

In addition to being a deduction rather than a credit, the deduction also has higher income limits than the Hope and Lifetime credits (but not the American Opportunity Tax Credit). While Hope phases out at $58,000 (single) / $116,000 (joint) and Lifetime phases out at $60,000 (single) / $120,000 (joint), the income limits for the Tuition and Fees Deduction were $80,000 for single filers and $160,000 for joint filers. However, the American Opportunity Tax Credit now has the highest income limits of the tax benefits for tuition, phasing out at $90,000 (single) / $180,000 (joint).

In recent years, the number of tax filers claiming the Tuition and Fees Deduction has dropped off considerably, falling from 2.9 million in 2008 to 1.2 million in 2011. This is due in large part to creation of the American Opportunity Tax Credit, which is partially refundable and which has even higher income limit phase outs than the Tuition and Fees Deduction.

Exclusion for Qualified Scholarships (IRC Sec. 117)

One of the oldest tax benefits for higher education is the exclusion for qualified scholarships. Since 1954, tax filers have been able to exclude from their income all or part of the funds they receive through a scholarship. Up until the 1986 tax reform bill (P.L. 99-514), students could exclude scholarship funds for tuition and many other college expenses from their income. Today, students may only exclude those scholarship funds used to cover expenses directly related to education (e.g., tuition, fees, books). Scholarship funds used to cover room and board and other expenses are subject to taxation.

Personal Exemption for Dependents Ages 19-23 (IRC Sec. 151 & 152)

While typically a parent cannot claim a child over the age of 18 as a dependent for federal income tax purposes, if a child is ages 19-23 and is enrolled full time for at least five months of the year at a school with a regular teaching staff, course of study, and a regularly enrolled student body, a parent may claim a personal exemption for the child. For tax year 2013, a parent may receive a tax benefit of $3,900 for each qualifying dependent. For tax year 2010-2012, there were no income limits for claiming a personal exemption. However, for tax year 2013 and beyond, a personal exemption phase-out applies. The phase-out level for single tax filers is $250,000 - $372,500 and for married tax filers filing jointly $300,000 - $422,500.

Gift Tax Exclusions for Higher Education Expenses (IRC Sec. 2503(b) and 2503(e))

Under current federal tax law, two gift tax exclusions exist that may be used to cover higher education expenses. First, under IRC Sec. 2503(b), a donor may give any individual up to $14,000 a year (tax year 2013 limit) for higher education expenses without incurring the federal gift tax. Second, in addition to the general annual gift tax exclusion, a donor may make a direct payment for tuition (no limit) to an institution of higher education on behalf of an individual without incurring the federal gift tax (IRC Sec. 2503(e)). This second gift tax exclusion is for tuition only and does not include payments for books, supplies, or room and board. There are no income restrictions on these gift tax exclusions.

Student Loan Interest Deduction (IRC Sec. 221)

The ability to take a federal deduction for interest paid on student loan debt is one of the oldest federal higher education tax benefits and one that has been allowed and disallowed at various points in time. Prior to 1986, student loan interest, like other types of personal debt (e.g., mortgage, credit card, auto), was deductible under the federal tax code. The 1986 comprehensive tax reform law (P.L. 99-514) disallowed deductions for all forms of personal debt interest other than mortgage interest, including student loan interest.

The ability to deduct student loan interest remained out of the tax code for the next ten years until passage of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-34). This law restored the deduction; however, students were only able to take the deduction for the first five years of repayment. The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 (P.L. 107-16) temporarily lifted the five-year rule, and the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-240) permanently lifted the limit. Today, if student borrowers meet the other eligibility requirements, they may take the deduction for as many years as they pay interest on their student loans. In tax year 2011, 8.2 million tax filers deducted a total of $8 billion in student loan interest.

Tax-Free Treatment of Student Loan Cancellations and Student Loan Repayment Assistance (IRC Sec. 108(f))

Generally, any portion of a student loan that is cancelled or forgiven must be included in gross income and therefore be subject to tax. However, in certain circumstances federal tax law excludes such loan forgiveness as taxable income. To qualify for tax-free treatment the loan must have been made by a qualified lender and require that the student work for a certain period of time, in a certain profession, and for any of a broad class of employers. Two of the best known examples of student loan cancellations qualifying for tax-free treatment are the Public Service Loan Forgiveness and Teacher Loan Forgiveness programs authorized under Title IV of the Higher Education Act.

Additionally, payments that students receive from their participation in certain health service loan repayment programs are also tax-free. These programs are:

• The National Health Service Corps Loan Repayment Program.

• A state education loan repayment program eligible for funds under the Public Health Service Act.

• Any other state loan repayment or loan forgiveness program intended to increase the availability of health services in underserved or health shortage areas.

Over the years, Congress has added education-related provisions to the tax code to assist employers in attracting and retaining talented employees and to assist employees in continuing their education and obtaining new knowledge and skills. Three of these employment-related provisions are the Employer-Provided Educational Assistance provision, the Employer-Provided Qualified Tuition Plan, and the Business Deduction for Education-Related Expenses.

Employer-Provided Educational Assistance (IRC Sec. 127)

Under section 127 of the Internal Revenue Code, up to $5,250 received in employer-provided educational assistance may be excluded from an employee’s gross income. This educational benefit may be used at either the undergraduate or graduate level and may be used for payments for tuition, fees, books, supplies, and equipment. Unlike the business deduction for education-related expenses discussed later, with few exceptions education courses covered by section 127 may be either job-related or non-job-related.

This exclusion for employer-provided educational assistance has its origins in the Revenue Act of 1978 (P.L. 95-600). Congress has extended this educational benefit many times over the last 30 years and most recently made the benefit permanent in 2013 as part of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-240).

According to a 2010 study, close to 1 million employees annually benefit from employer-provided education assistance under section 127, and employees receiving this benefit have pursued their educations across various levels and academic disciplines.[3] According to the same 2010 study, of the degrees pursued by beneficiaries in 2007-2008, 3 percent were at the certificate level, 26 percent were associate’s degrees, 18 percent were bachelor’s degrees, 36 percent were master’s level degrees, 6 percent were other graduate level degrees, and 11 percent were not in a degree program.

Employer-Provided Qualified Tuition Reduction (IRC Sec. 117)

To attract and retain faculty and other employees, a number of institutions of higher education provide their employees and employees’ spouses and dependents with a benefit to study tuition-free or at a reduced rate of tuition. Additionally, to attract high-quality graduate students, institutions will often waive or reduce tuition if a graduate student teaches or conducts research for the institution. Section 117 of the IRC provides for tax-free treatment of such qualified tuition reductions. As indicated below, different rules apply at the graduate level and at education below the graduate level.

Business Deduction for Work-Related Education Expenses (IRC Sec. 162)

Employees who can itemize their deductions may be able to take a deduction for education expenses related to their work. To qualify for the deduction, the education must meet two tests. First, the education must be required by an employer or the law in order for the employee to keep his or her current salary, status or job. Second, the education must maintain or improve skills needed in the employee’s present work. An example of a qualifying work-related education expense would be continuing education courses for certified public accountants. To maintain their license to practice, certified public accountants are required by law to take a given number of education courses each year.

As the cost of college continued to escalate in the 1980s and 1990s, Congress turned to the tax code to create tax-preferred benefits for college savings. Over the years, Congress authorized two additional tax benefits for education savings – a tax exclusion for interest earned on education savings accounts (529 Plans) and the waiving of the penalty on early withdrawals from Individual Retirement Accounts used to pay for qualified education expenses.

529 Plans (IRC Sec. 529)

529 plans, named after the section of Internal Revenue Code that stipulates their tax treatment, were created by the states as state-sponsored investment vehicles to encourage families to save for college. The specific federal tax benefit of 529 plans to families is that the distributions are tax-free if used to pay for qualified higher education expenses.

The first such plan was created by the state of Michigan in 1986. Initial confusion regarding the tax treatment of these plans led the U.S. Congress to enact legislation to clarify their tax treatment. Congress first recognized 529 plans in the Small Business Job Protection Act of 1996 (P.L. 104-188) and made subsequent changes to them in 1997 under the Taxpayer Relief Act (P.L. 105-34). It should be noted that with respect to federal income taxes, these plans allowed for tax-free growth of investments, but distributions were fully taxable. In 2001, as part of a broader set of tax reforms, Congress made distributions tax-free and that rule was made permanent in 2006.

Two types of 529 plans exist – prepaid tuition plans and college savings plans. While prepaid tuition and college savings plans have distinct differences, the federal tax treatment and benefit of these two types of plans is identical – under both types of 529s, distributions and withdrawals are tax-free if the funds are used to pay for qualified higher education expenses.

Under a prepaid 529 plan, a contributor (e.g., parent, grandparent, family friend) purchases a percentage of future tuition costs at current prices. The initial idea of the prepaid tuition plans was to provide families with a hedge against tuition inflation. Although prepaid tuition plans were the first type of 529 plan, the number of such plans has dropped considerably as skyrocketing tuition costs have ballooned future obligations. This has resulted in a decline in the popularity of prepaid 529 plans. There are currently 17 prepaid 529 plans and ninety 529 college savings plans across the nation.

Under a 529 college savings plan, contributors invest in a portfolio of mutual funds, stocks, bonds, and other investments with the final value of the 529 account determined by the performance of the plan’s investments. Many states offer a variety of 529 college savings plans some of which provide more aggressive investment opportunities as the beneficiary is younger and more conservative investments as the beneficiary approaches the age of enrolling in college.

Over the last decade, the total assets in state-sponsored 529 plans has grown considerably, from $58 billion in 2003 to $227 billion in 2013.

Additionally, in 2014, there were approximately 11.8 million 529 accounts with an average account value of $20,671. While the number of accounts and their assets have grown over time, only a very small number of American households have an account. According to the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finance, less than three percent of families save for college in a 529 or Coverdell account (discussed below). Further, those families with college savings plans are generally wealthier, having about three times the median income as families without a college savings account.

Coverdell Education Savings Accounts (IRC Sec. 530)

Coverdell Education Savings Accounts, named after the late Senator Paul Coverdell (R-GA), are yet another tax-preferred savings vehicle for education. Similar to 529 plans, the investments in Coverdell accounts grow tax-free and the distributions are tax-free provided they are used for qualified education expenses. However, there are significant differences between the two. First, unlike 529 plans that are strictly for college education, a Coverdell can pay for education expenses at the elementary, secondary, or postsecondary levels. Additionally, unlike 529 plans that have no annual contribution limits to accounts and no income restrictions on contributors, Coverdell accounts limit annual account contributions to $2,000 and limit tax payers with an income of more than $110,000 (single)/$220,000 (joint) from making contributions. Finally, Coverdell accounts, a benefit provided for in the federal tax code, are neither state-sponsored nor state-run savings plans.

Coverdell Savings Accounts were first created as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 (P.L. 105-34) and were initially called Education IRAs. Most recently, the $2,000 annual contribution limit was made permanent as part of the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (P.L. 112-240). Barring such a change, the annual limit would have dropped to $500 in 2013.

Education Savings Bonds Exclusion (IRC Sec. 135)

The savings bonds tax exclusion allows qualified taxpayers to exclude from income all or part of the interest earned on eligible U.S. Savings Bonds to pay for qualified higher education expenses for the taxpayer, spouse, and their dependents at any educational institution eligible to participate in a student aid program administered by the U.S. Department of Education. Qualified education expenses include required tuition and fees. They do not include books or room and board. A taxpayer must also meet income limit qualifications. For tax year 2013, the income limit for singles is between $74,700 and $89,700 and for married filing jointly the phase-out limits are between $112,050 and $142,050.

Early Withdrawals from Individual Retirement Accounts (IRC Sec. 72(t))

Under normal circumstances, if an individual takes a distribution from an IRA – Traditional or Roth – before the age of 59 ½, the individual must pay a 10 percent penalty for the early distribution in addition to any regular income tax that is due. However, if the distribution is used to pay for qualified higher education expenses for the taxpayer, spouse, or dependents at any educational institution eligible to participate in a student aid program administered by the U.S. Department of Education, the 10 percent penalty is waived. Qualified education expenses are tuition, fees, books, supplies and equipment required for attendance. If the student is enrolled on at least a half-time basis, room and board may be considered a qualified education expense.

[1] U.S. Government Accountability Office (2012). Improved Tax Information Could Help Families Pay for College (GAO-12-560).

[2] U.S. Government Accountability Office (2012). Improved Tax Information Could Help Families Pay for College (GAO-12-560).

[3] National Association of Independent Colleges and Universities & Society for Human Resource Management (2010). Who Benefits from Section 127: A Study of Employee Education Assistance Provided under Section 127 of the Internal Revenue Code.