Soy Story

Weekly Article

Official White House Photo by Shealah Craighead

Nov. 7, 2019

If you’re seeking a potential solution to the United States’ on-again, off-again trade war with China, look no further than the humble soybean.

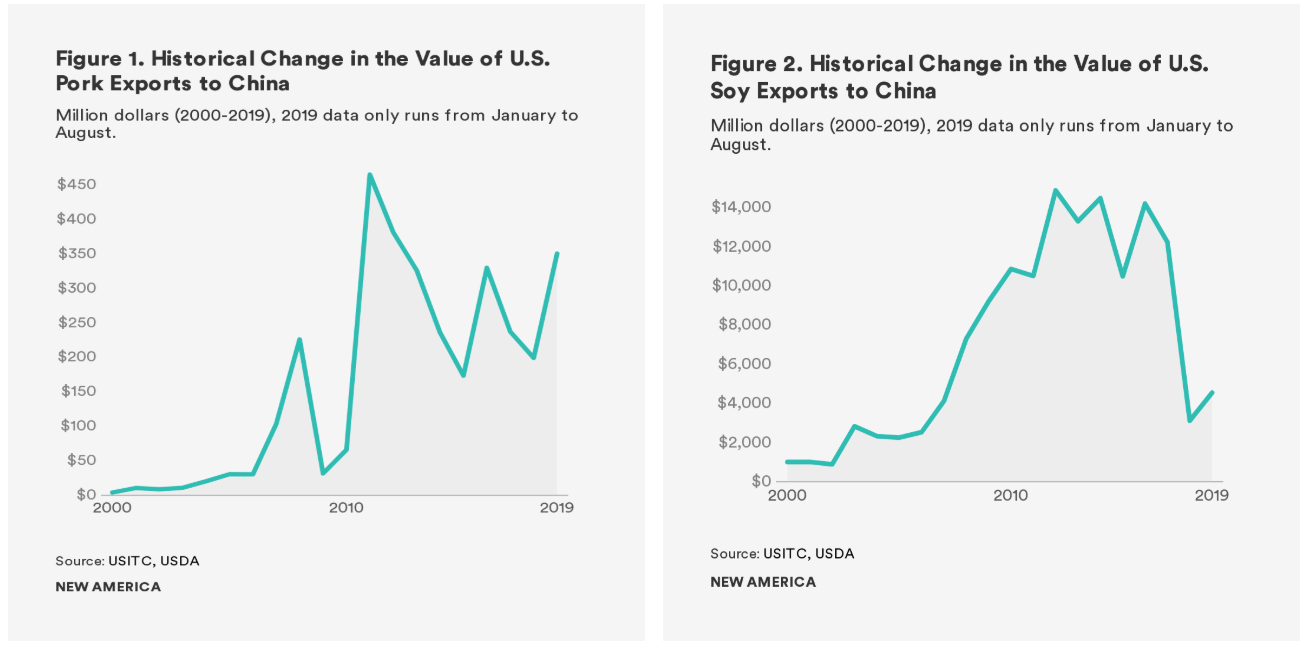

Just as the trade war seemed on the brink of catastrophe, negotiators reportedly came to a disaster-staving agreement earlier this month in Washington, D.C. From what we know (the formal agreement is still being written), the United States agreed to delay raising tariffs by 25-30 percent on $250 billion worth of Chinese products in exchange for China purchasing $40-50 billion worth of American agricultural products. And while we don’t yet know what agricultural products China agreed to buy, it’s likely to be soy and pork.

The rationale for pork is fairly straightforward: China is currently in the midst of a devastating outbreak of African swine fever, which has prompted a dramatic contraction of available pork—along with soaring prices. Soy, on the other hand, is a more complicated case. This little legume captures the sheer complexity of U.S.-China trade relations—and the convergence of natural and political factors binding the two economies.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance of China’s market to American soy farmers. Between 2013 and 2017, 50 percent of U.S. soy exports were destined for China. Eight of the top 10 soy-producing U.S. states (which together account for 20 percent of global soy production) voted for Trump in 2016; Iowa, which Trump carried by the largest margin of any Republican candidate since Reagan, exports an estimated 75 percent of its soybeans to China, where they’re used primarily in animal feeds. In short, a significant portion of the President’s voting base is comprised of farmers, attaching a political price tag to any action that might see those farmers harmed—including a trade war with their largest market.

Source: New America

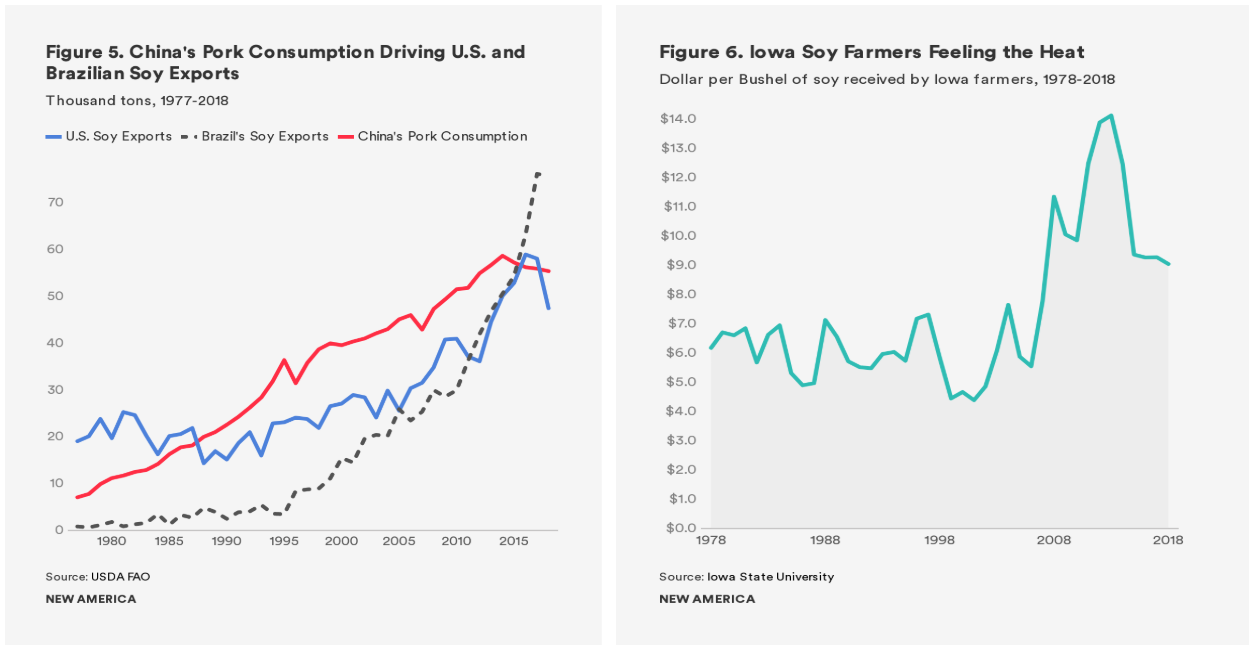

As it urbanizes, China’s burgeoning middle class is shifting its dietary patterns to include more protein and dairy: Since 1990, the country’s pork consumption has increased by over 100 percent, as have its imports of soy. This, in turn, has opened a massive and profitable market for U.S. agricultural products. Today, China relies on imports for 87 percent of its soy supply—a somewhat ironic development, considering it was where soy first took root. Remarkably, given the costs of feeding 20 percent of the global population on a shrinking water table and just 9 percent of the planet’s arable land, China is nearly self-sufficient in staple crops. By prioritizing grain self-sufficiency, the country is able to meet the majority of its food needs with domestic resources—but not without associated environmental impacts from heavy fertilizer and pesticide application.

While soy is its chief U.S. agricultural import, disease outbreaks among livestock have also forced China to import large quantities of pork from the United States on several occasions over the past decade. This year’s outbreak has killed an estimated 300 million Chinese pigs thus far, forcing pork prices up and the country to turn to imports.

When disease isn’t destroying its livestock, China is nearly self-sufficient in pork. However, the livestock industry has immense environmental consequences—waste from the swine industries of China, Vietnam, and Thailand, for example, contributes more to pollution in the South China Sea than do human sources from those three countries.

Source: New America

The livestock industry’s overwhelming reliance on imported feed products—such as soy—also carries a host of geopolitical implications. Today, the United States is one of the world’s largest producers of soy, while China is the world’s leading importer. Thus, China’s meat consumption is inextricably tethered to soy production in the Americas—meaning the very profitable growth in exports enjoyed by U.S. soy farmers over the past few decades has largely been a result of rising Chinese demand.

While this reliance on imports for a key natural resource is undoubtedly costly, it’s also a lever upon which China isn’t afraid to pull—as has been demonstrated throughout the last few years of trade negotiations.

In other words, disparate concerns are converging. Higher meat prices result in upset consumers questioning party legitimacy—a major fear of the Chinese Communist Party. Tariffs on soy imports lead to upset farmers—a major fear of the Trump administration. Thus, after three unsettling years, aligned interests may signal a possible end to the trade war.

Source: New America

There are a plethora of issues that still need to be addressed in the context of U.S.-China trade relations, but with a combination of natural and political forces bringing both countries to the negotiating table, a deal might finally be struck. Ideally, the deal’s first phase will temporarily alleviate pressure on both countries’ economies, paving the way for a larger agreement encompassing more robust measures, such as protection from intellectual property theft and forced technology transfers. At worst, American farmers will get paid, Chinese farmers will acquire the necessary ingredients for developing new livestock, and Chinese citizens will be able to enjoy clean pork.