Equality Within Our Lifetimes? Top Four Policy Takeaways for Making Global Gender Equality a Reality

Blog Post

March 6, 2023

We are, the reports say, 99 years from achieving gender parity, 257 years from equal labor force participation, and 268 years from closing the economic gender gap. Each year brings a new study announcing these sober, centuries-long estimates of how far we are from achieving the dream of gender equality around the world.

In a new book, Jody Heymann, Aleta Sprague, and Amy Raub from the WORLD Policy Analysis Center at UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health argue that worldwide gender equality may be closer to reality than we believe. The key, they say, is in reforming a host of common policies that reinforce gender inequality and introducing new policies proven to give women a shot at full economic participation.

The team of researchers based their findings on a dashboard they built to study and compare policies and their impact across the 193 member countries of the United Nations. From this study, they offer concrete recommendations that economies worldwide should adopt to accelerate the slow crawl toward gender equality.

Here are some of the major recommendations provided by the researchers in a recent discussion with the Better Life Lab. You can view our chat below, read the entire book for free, and access all the charts included in this post here.

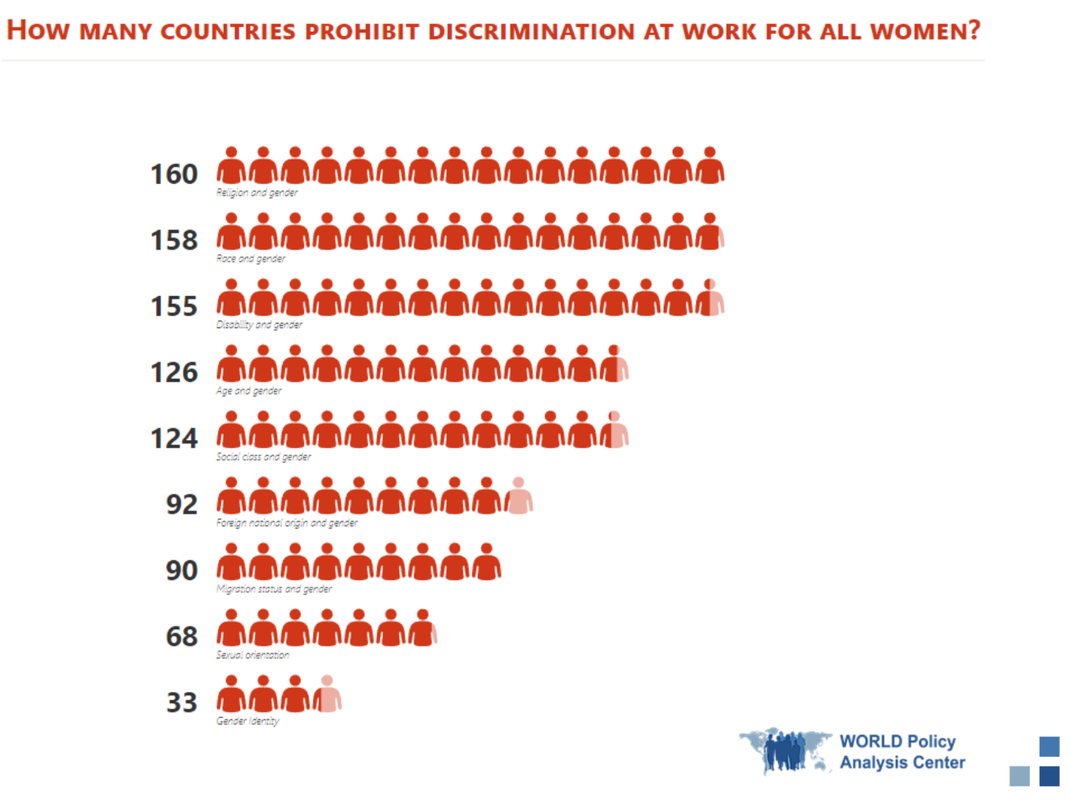

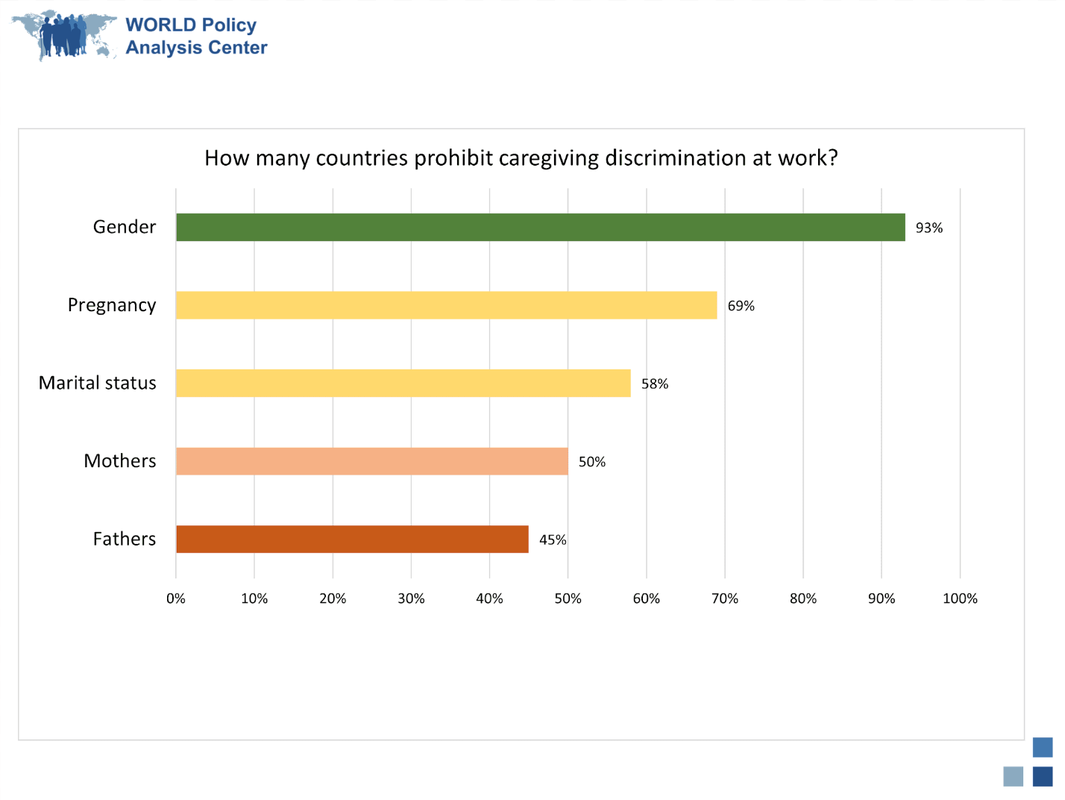

1-While most countries ban discrimination on the basis of gender in hiring and pay, more specific prohibitions are needed to give women with multiple marginalized identities protections at work.

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

Many countries’ existing laws leave room for employers to discriminate against women at work when it comes to advancement and opportunities for training. Furthermore, while women as a whole are protected from discrimination, they may face discrimination for many other reasons that intersect with their gender identity—such as being foreign-born, queer, or trans or non-binary. Equality within Our Lifetimes makes it clear that policy must explicitly prohibit these common forms of discrimination, or specific groups of women will continue to face discrimination at work.

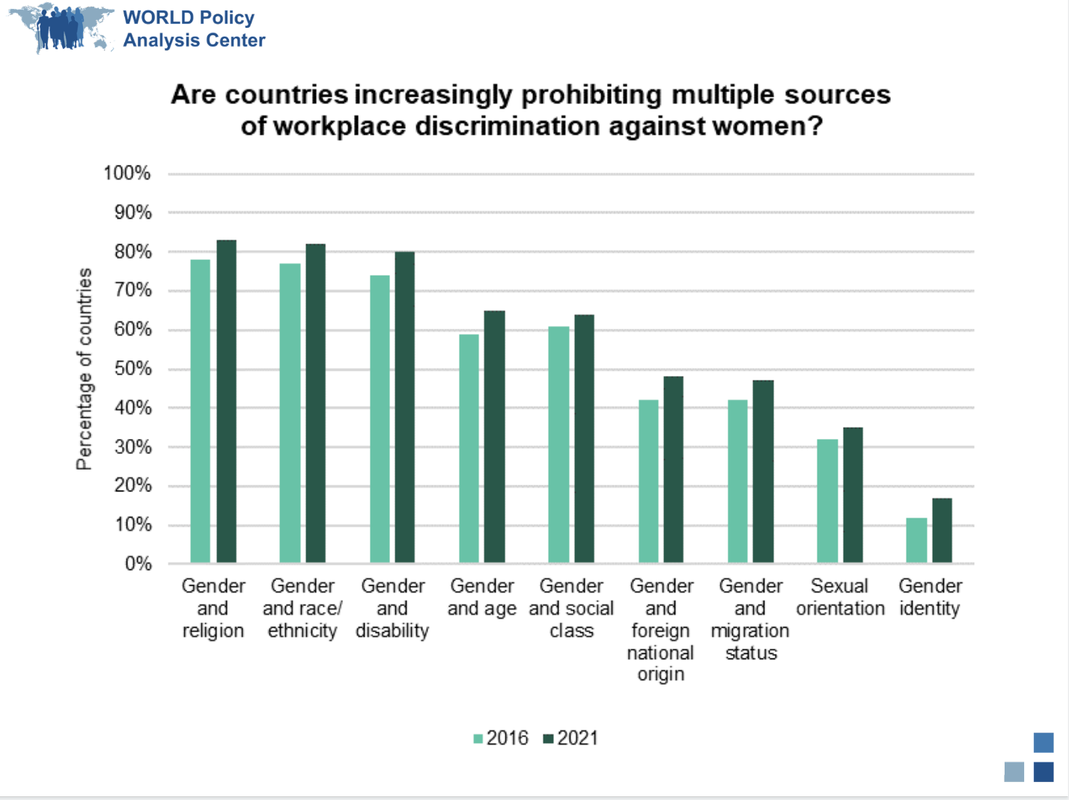

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

The good news is the authors find more countries have begun to tackle these forms of discrimination, since 2016.

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

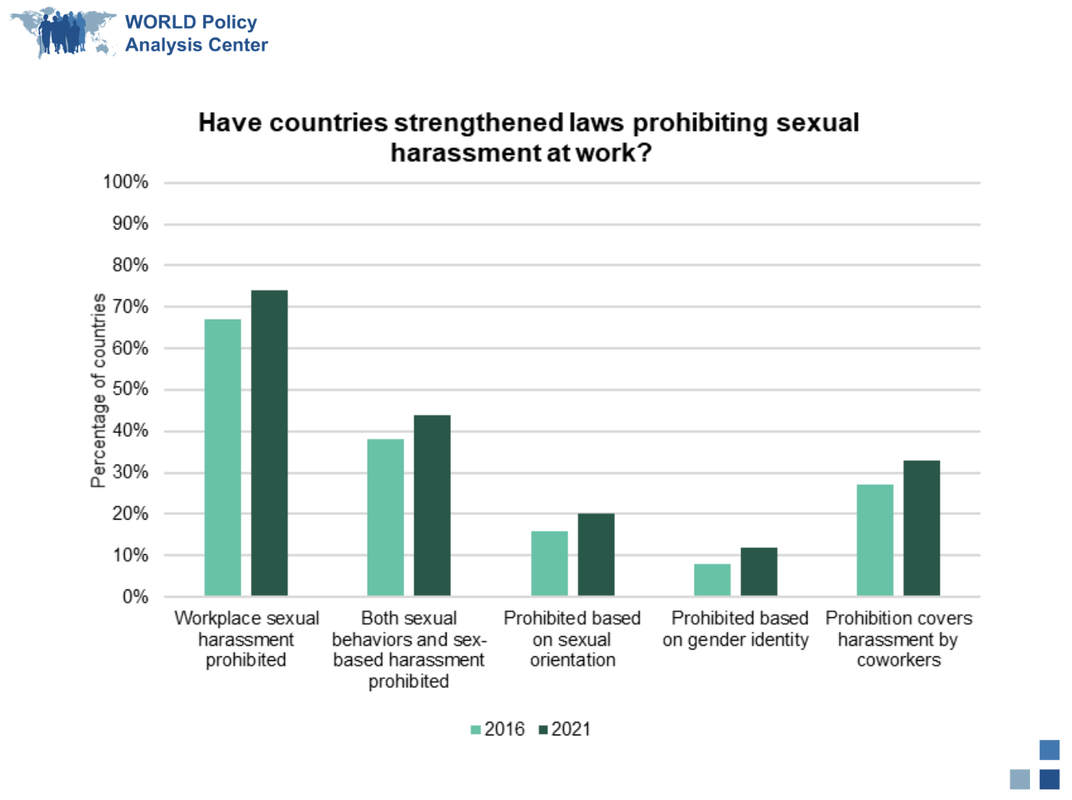

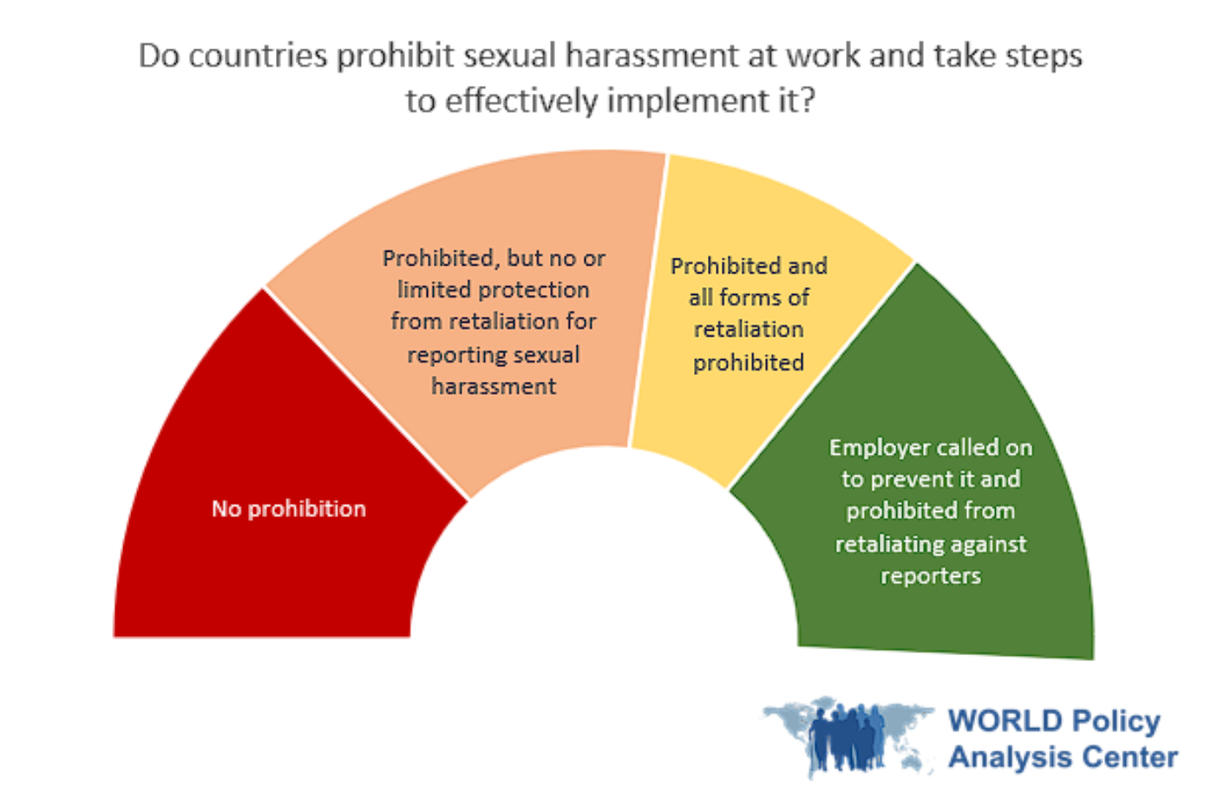

2-Bans on sexual harassment are neither universal, nor wide-reaching enough to protect complainants across all levels of the work force.

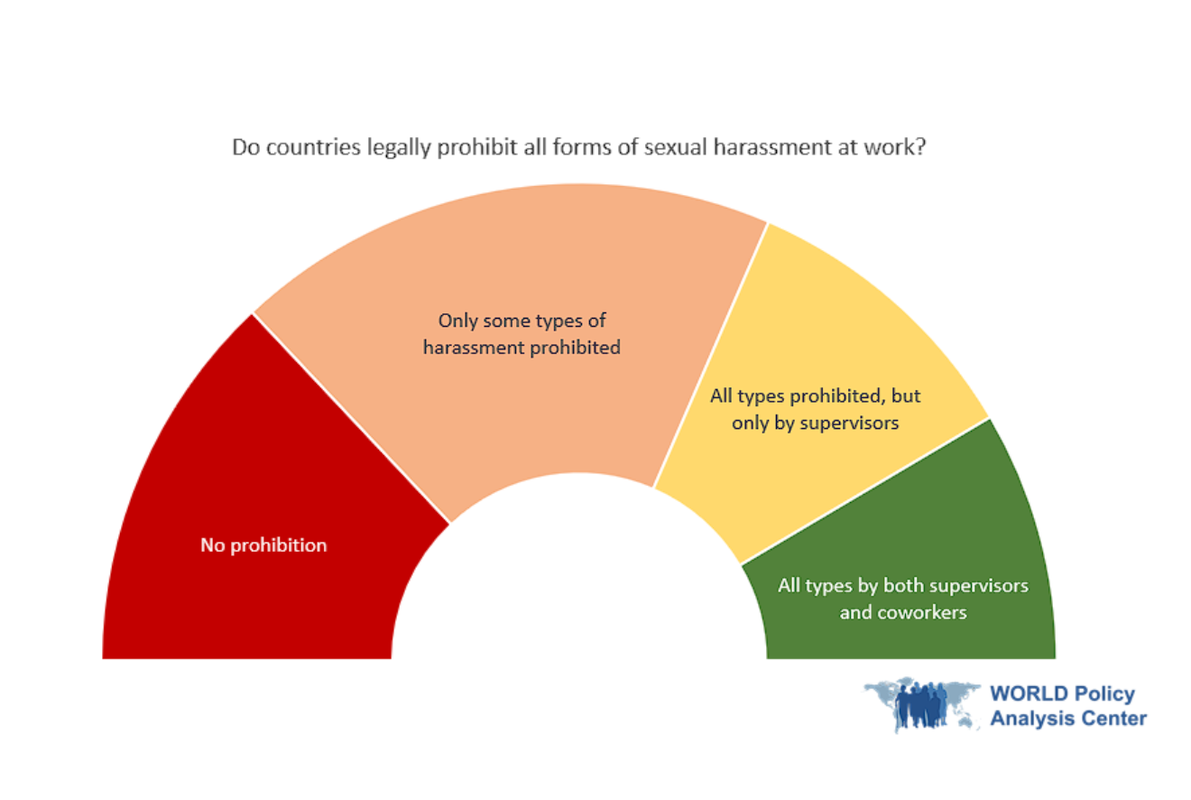

Despite progress since the #MeToo movement went global in 2017, the authors find that nearly one in five countries doesn’t prohibit sexual harassment at work. And fewer than half of countries prohibit sexual harassment by coworkers, targeting instead only harassment from superiors. But sexual harassment by a colleague at any level may cause women to leave a workplace, thus causing them to lose the opportunities for earning and advancement that come with being employed.

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

Another gap in existing sexual harassment laws is that while harassment may be prohibited, it might remain exceedingly difficult—and frightening—for someone to actually flag harassment and have their employer attend to it due to limited protections from retaliation.

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

Until laws are corrected to protect women from the full spectrum of gender-based harassment they may face at work, and from retaliation if they blow the whistle, equality will remain a distant dream.

3-Laws must support workers requiring time off so that they can provide unpaid care to infants, themselves, and loved ones.

One major driver of gender inequality is the disproportionate amount of unpaid work, especially caregiving, that women worldwide do compared to men. According to Equality within Our Lifetimes, women currently perform 265 minutes of unpaid work a day, compared to 83 minutes for men. These numbers vary by country, but it’s clear that where women do the most unpaid work, they do less paid work and have lower capacity for civic and political engagement.

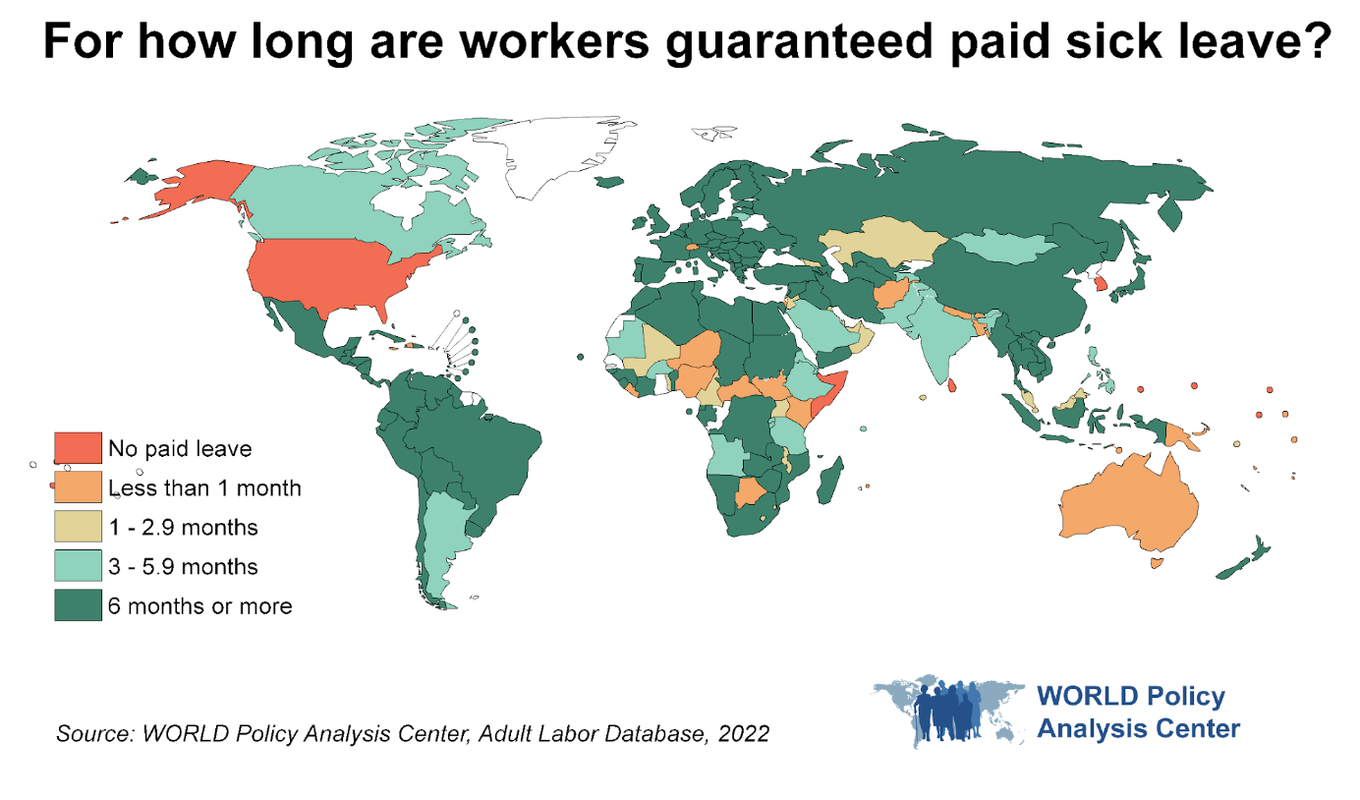

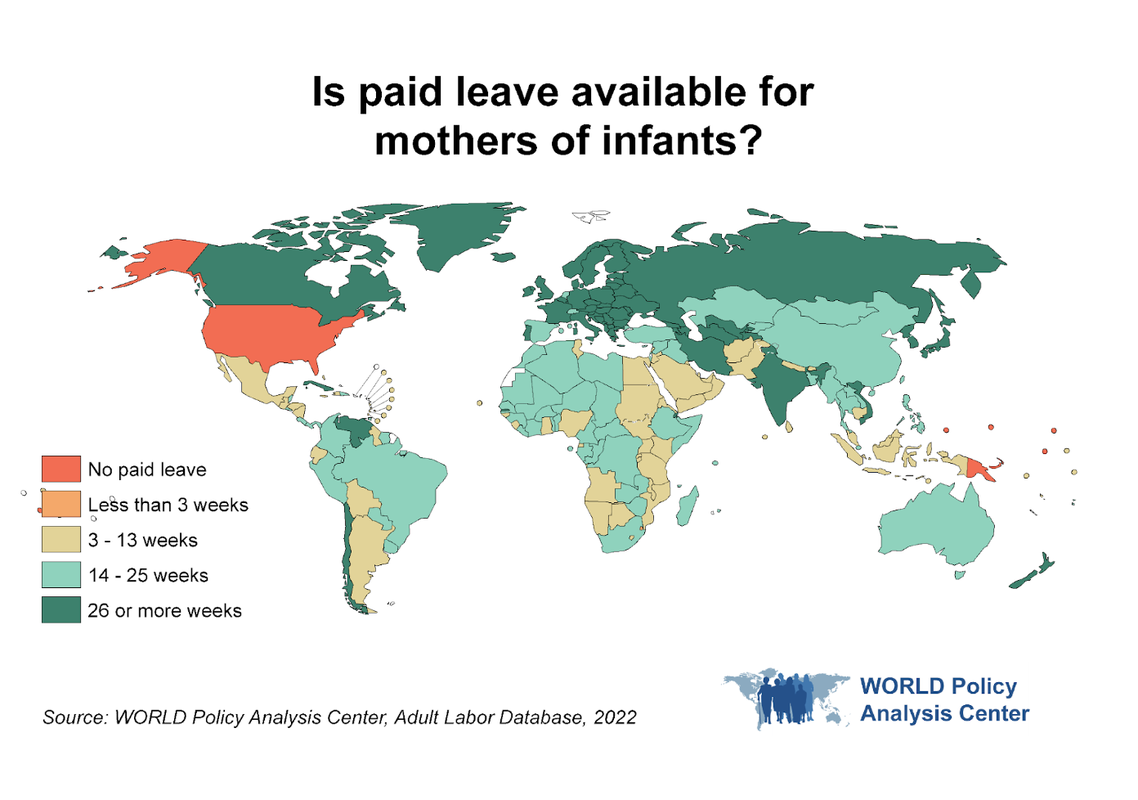

Paid leave laws, which allow workers to take short or long breaks from their jobs to provide care, are key to ensuring those who perform care are not penalized economically. In the U.S., our laws are particularly insufficient to this end. Most workers only have access to as much paid leave as their employer offers, and no federal law gives them the right to paid leave to care for themselves, loved ones, or a new infant.

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

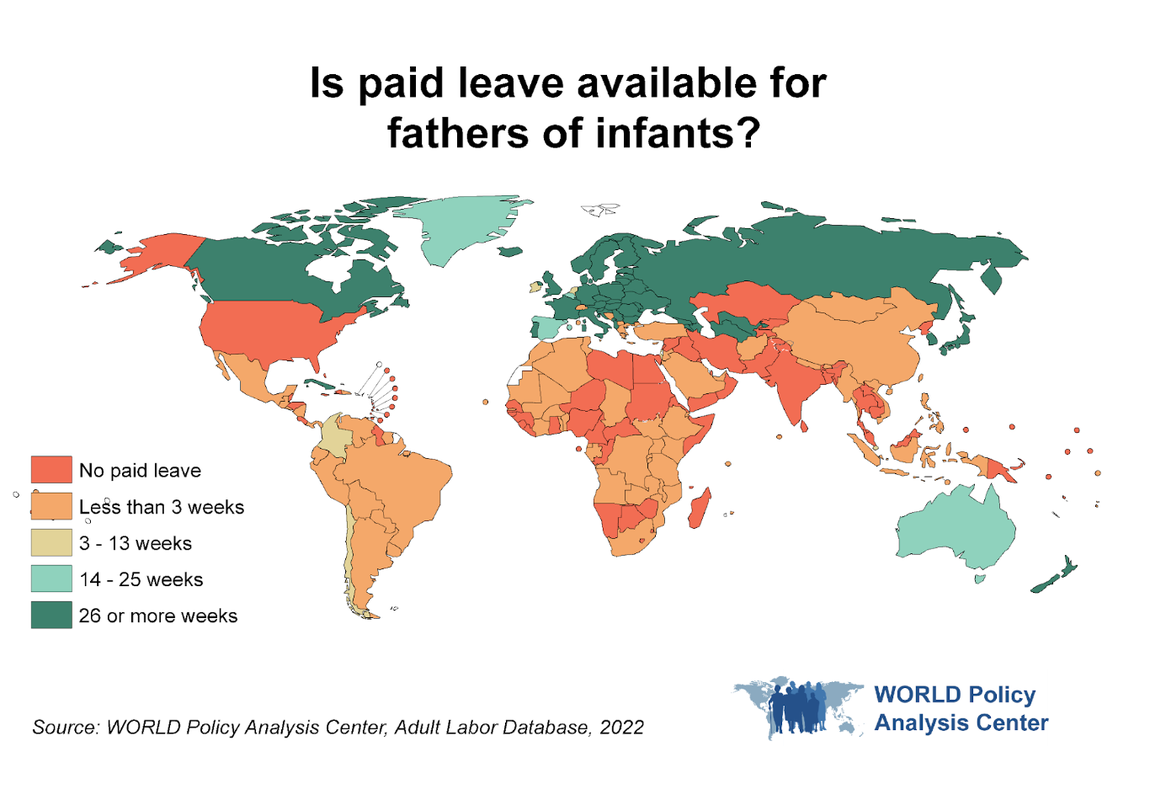

The good news is that outside the U.S. almost every other country guarantees paid leave to new mothers, and an increasing number are offering it to new fathers. As Heymann, Sprague, and Raub write, however, there remains immense work to be done to make paid leave available to all workers in all types of family structures, and especially to encourage men to use leave at the same rates as women. “[I]n far too many countries,” the authors write, “the leave length remains grossly unequal: 74 percent of countries provide no paid leave or less than three weeks of paid leave to fathers, compared to only 4 percent for mothers.” Closing that gap is critical to ensuring that the cycle of women doing the bulk of caregiving does not continue for future generations.

When it comes to leave laws, there’s progress to be made on all fronts, especially in the world’s largest economy, until they produce more equal outcomes across gender.

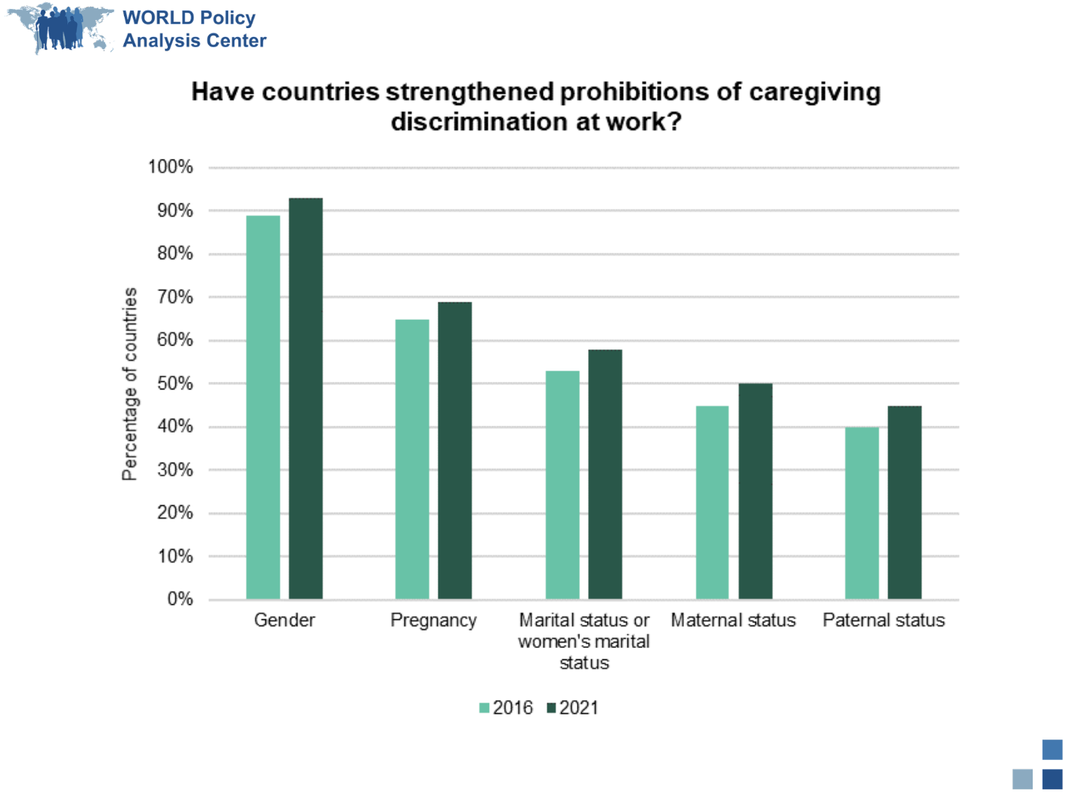

4-Countries should not only protect workers from discrimination based on identity but also based on caregiver status.

There’s more to making our economies fair to caregivers than just leave laws. Most people will, at some point, need to provide care and earn income simultaneously. Unfortunately, caregivers face barriers at work throughout their careers, and not just in those precious months around a health crisis or new birth. Indeed, a subset of women, mothers, may face the highest rates of job discrimination and stigma that they are subpar workers, despite abundant evidence to the contrary.

Some countries have already understood that anti-discrimination law must go beyond naming gender as a category of discrimination, and protect mothers, fathers, married people, and pregnant people against workplace bias, too.

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

Once again, the good news is these types of anti-discrimination laws for caregivers are on the rise. This includes the U.S., which at the end of 2022, finally passed the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act into law.

Heymann and Sprague noted in their chat with the Better Life Lab that labor unions and other pro-worker organizations can make huge inroads when they unite with other civic organizations to push individual workplaces and policymakers forward. The task ahead lies in pushing all powerful institutions toward taking on a greater interest in the care economy and in those who provide the unpaid care our whole economy rests on.

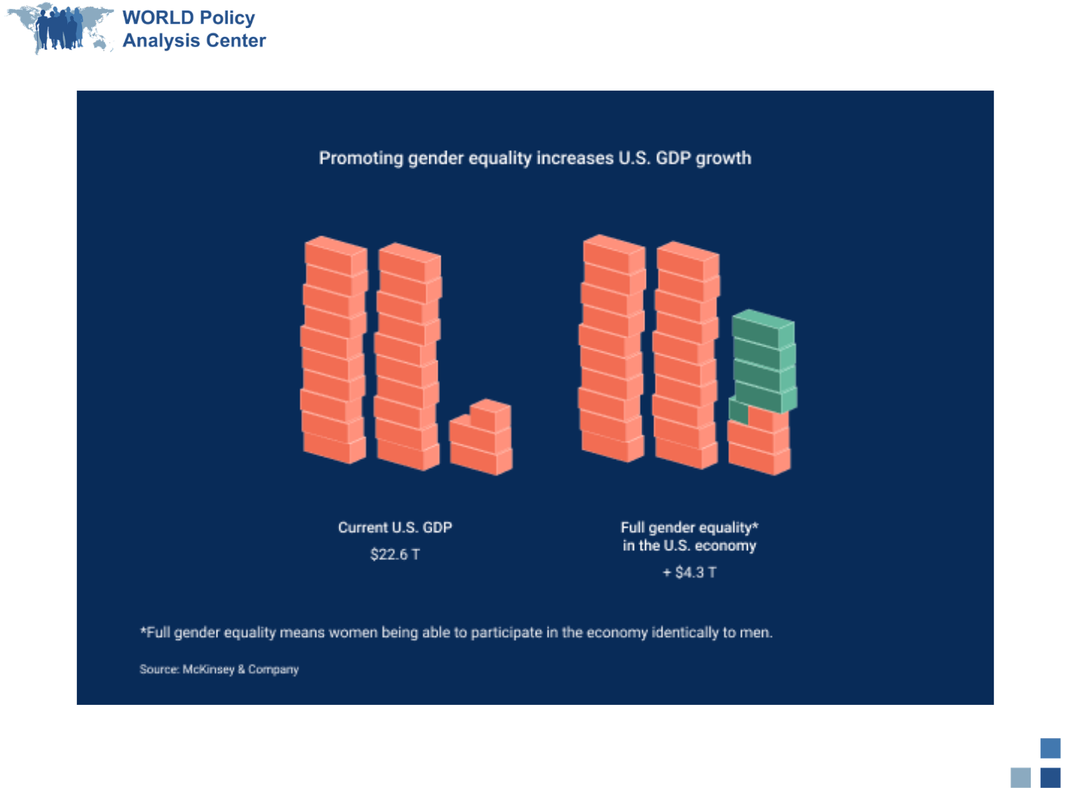

While many politicians focus on short-term problems and solutions, the problem of gender inequality, including undervaluing care, is already having long-term impacts on our economies.

Source: WORLD Policy Analysis

In the last two years, U.S. policymakers were closer to passing major care-supportive policies than in decades. “The argument against it was we couldn’t afford these policies, along with everything else,” said Heymann. But from what she has seen in the data, she concludes instead, “I don’t think we can afford not to.”