In “Mom’s Hierarchy of Needs,” Health and Happiness Mean Energy, Not Time Management

A Better Life Conversation with Leslie Forde

Blog Post

Sept. 15, 2025

Moms in the United States are struggling. Since 2016, the number of moms who say their mental health is excellent has dropped from 38 percent to 26 percent, according to research led by Columbia University assistant professor Jamie Daw. 48 percent of parents said their daily stress was overwhelming, compared with just 26 percent of other adults.

Several years ago, Leslie Forde was at the top of her field, married, with a toddler and a newborn baby. But she came back from maternity leave to discover that both her work and parenting stress had skyrocketed. Stress, a lack of sleep, and extreme mental fatigue eventually took such a toll that she felt she had no choice but to take a step back at work.

It was her desperation to understand what happened to her and how to reduce that stress that drove her to start Mom’s Hierarchy of Needs, a research-driven organization supporting mothers’ mental health through individualized support and workplace interventions. In a new book, Repair with Self-Care: Your Guide to Mom’s Hierarchy of Needs, Forde shares the lessons she has learned and reframes the idea of self-care as something busy moms not only can make time for, but must make time for in their lives.

My conversation with Forde about what she means by “Mom’s Hierarchy of Needs” and what sets her framework apart from other self-care and productivity advice has been edited for length and clarity.

Haley Swenson: Tell me about Mom's Hierarchy of Needs and your journey to writing this book.

Leslie Forde: Everything changed when I returned from maternity leave after having my second baby. I went from managing two departments to a situation where multiple team members had to take unexpected FMLA leave. The market conditions had shifted, and I was being asked to bring my most strategic, clear-thinking self to work—which is literally what I'm paid for—while I was completely depleted. I was sleeping in 90-minute increments with a newborn and toddler, and physically not doing well.

There were warning signs I was ignoring. Days I didn't remember driving to work. Times I'd race through the parking garage, run up to the mother's room, and realize I'd left the breast pump at home. I started hallucinating from sleep deprivation, and it was apparent to others—for the first time in my life people asked if I was okay.

What was once a dream job became completely unsustainable. Even though I was a VP at a public company, I felt too vulnerable to say I was struggling. I mean, I'd just been away for 12 weeks. How could I ask for more time or different arrangements?

So I did something I never thought I'd do—I downshifted. Took a role with one direct report, a 40% pay cut, and negotiated a four-day work week. It still took over two years to recover and regain clarity after that burnout.

During recovery, I was approached by a mental health startup founder who asked, "Why are moms so stressed?" And I said, "How much time do you have?" In that moment, I just said, "There's Maslow's hierarchy of needs, and there's mom's hierarchy of needs." It rolled out, and I felt it. I drew it on paper, got curious about what it would look like for others.

Haley Swenson: What does that hierarchy look like?

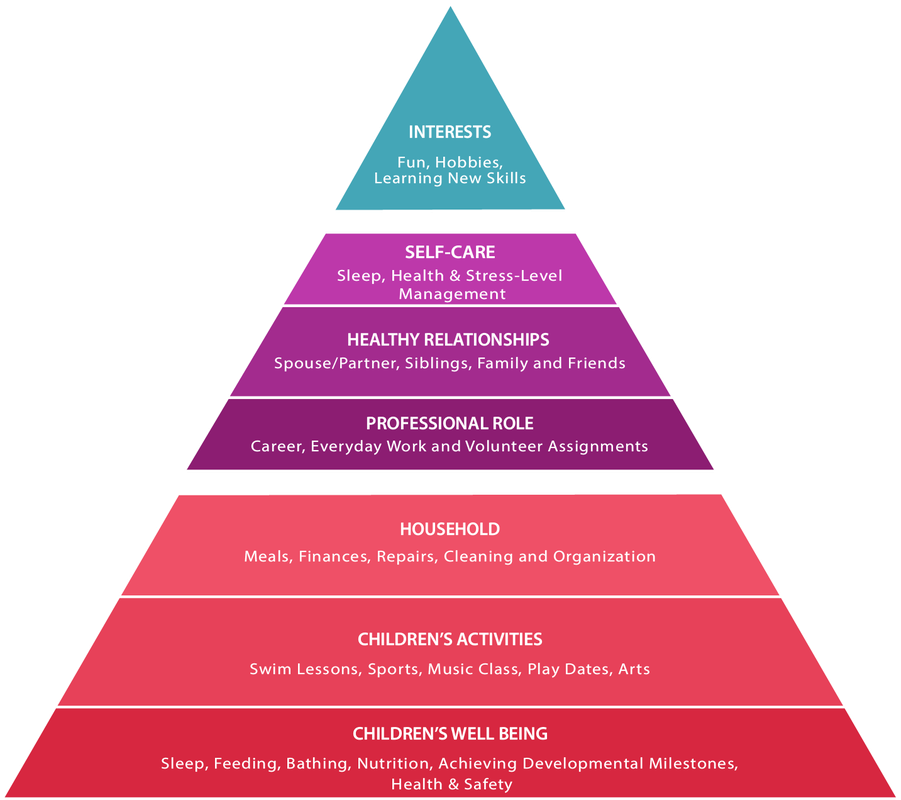

Leslie Forde: At the base, we prioritize our children's health, milestones, well-being, activities. The next layer: household responsibilities, making the home feel and be a certain way. Then professional roles. All those bottom layers—the reason we never get to the top, which is self-care, involving sleep, movement, stress management, healthy relationships—is because what we prioritize at the bottom is never done. It's perpetual.

Pre-children, you're in that mode of "when everything else is done, then I'll call that friend, see that movie, pursue that PhD, take that walk." But after kids, there's no "done." There's no “done” to children's well-being, certainly no done to housework. That was my wake-up call.

If I'm trying to do something impossible—wait for leftover time to take care of myself—and it's impossible, then I need to be ruthless about carving out time in my schedule.

Haley Swenson: Your book description says this is not a work-life balance book. What are we shooting for if not balance?

Leslie Forde: I don't believe work-life balance is feasible, and everyone who tries to achieve it is deeply disappointed when they can't. What I think is possible is managing energy in a way that allows you to serve your highest-importance goals with more fidelity, in a way that feels good to you, making trade-offs less significant, and giving yourself space for restorative self-care.

That piece is not up for debate. You have to move, care for your body, mental and physical health, emotional well-being. It doesn't have to look like a spa day—very few of us get those. It doesn't have to be an hour of therapy plus workout daily. Even if it's five minutes when your kid is quiet and you splash cold water on your face, or close the bathroom door and put your child in the pack-and-play with Play-Doh—it has to be part of your day-to-day life fabric. It can't be episodic vacations twice a year, which aren't exactly relaxing for moms with little kids anyway.

Haley Swenson: You ask moms to make a shift from thinking about time management to energy management. How did you get there?

Leslie Forde: You'll see this concept in psychology research—the idea of flow, getting into that state where things feel effortless, you're in your zone of genius. It's usually through a male lens, not through motherhood or caregiving.

There are times when you can multitask without sacrificing much, but there are times when you feel really drained. Many of us feel drained by 8 AM because we've already thought a thousand times, solved a million problems, dealt with sippy cups, chased kids around getting dressed, handled tantrums. You haven't started your day and already feel like you've lived a thousand lives.

If you understand what those drains look like—some personal to who you are, some about making too many trivial decisions when your body has a biological limit—don't spend it on sippy cups. Come up with routines. My kids had their own colors for cups and plates. I know which plates I use for which things. I'm not reinventing that because I don't want to think about it multiple times daily. There's a tax on my clarity.

You can choose your own system and continue pouring energy into what you want to obsess over. I obsess over food—I love cooking and meals. But other food decisions are routine because the mental energy cost is too high.

Haley Swenson: This connects to mom guilt around time with kids. Many working mothers think, "I need to spend more time with my kids, so I can't go to the gym." But what's the quality of that time if you're depleted?

Leslie Forde: Exactly. What's the quality of presence you can give? What's your patience level? We've all snapped when we didn't want to, because 15 things happened before that moment that added to this reservoir of depletion. You snap over something you wouldn't snap over if you were in a better state—if you were on vacation, if you'd have had eight hours of sleep.

Understanding that and choosing to put yourself in a better frame as much as possible, or knowing when you're not and making alternative arrangements—that's key. Physical energy is really hard without decent sleep. Pregnancy, postpartum, hearing a baby cry every two hours, worrying about kids, getting them up at dawn, perimenopause, menopause—women have this long period of sleep deprivation.

Sleep deprivation was part of how I lost my mind postpartum. We have to protect against it, even if it means not going to something you'd love to attend because it starts at 9 PM and you have to be up at 5 or 6 AM.

Haley Swenson: You include intellectual self-care as a category. Tell me about that.

Leslie Forde: I realized I'd become so narrow—narrowly expert on my job, then narrowly expert on my babies. I wasn't as broad as I wanted to be anymore. When this Mom's Hierarchy of Needs idea came to me, I wanted to be creative again. I'd always been a writer, but in my career, I was a business writer. Growing up, I wrote poetry, was a dancer, and a painter. I had this creative youth that was meaningful to me, but I erased and pushed it out as an adult because it was inefficient.

When I realized I was hungry to be creative, to put my own thoughts out there—not just company thoughts—to have the vulnerability and growth that comes from sharing my own ideas, I had to learn. I had to invest in self-education, and I was excited about that. I felt fed by it, fueled by it. I realized I was starving for intellectual stimulation, learning new things, pursuing interests through their twists and turns. That had always made me happy, so it was missing from my life.

Haley Swenson: Moms today are so tuned into their kids' needs for enrichment. We often go from home to work and back home again, thinking about building experiences for our kids, but not ourselves.

Leslie Forde: I would only caveat that I don't think we have space to step back. I feel like it's iterative. Maybe you get five or ten minutes of reflection here and there. Maybe instead of cleaning counters during nap time, you sit and look out the window. In the midst of being fully engaged with no time to yourself and very little sleep, you're choosing to carve out spaces for growth and health right in the middle of it.

Most of us can't go on weekend-long retreats to get back in touch with ourselves. If you can, go for it, but knowing that's out of reach because of time, money, childcare—find variations that work within how your life really is.

Haley Swenson: How do you think about the relationship between individual self-care strategies and broader systems change?

Leslie Forde: Well, there are two sides to that answer. We do need to take care of ourselves, as best we can. There's very little discretionary time, and we're socialized to be guilty about using it. I can break that cycle for people, help them see we're at greater risk for stress-related illness of every kind. All the self-sacrifice means we're less healthy, have shorter lifespans or health spans.

But the real answer is public policy change. It'll happen when we're grandparents, if ever. Knowing it won't happen in your lifetime frees you to make different choices. There are systems of work: changing norms, how managers reward people, what high performance looks like, moving away from responsiveness as a proxy for commitment. That's faster than public policy change but still hard.

Individual changes do impact systems. If you decide you absolutely refuse to pay late pickup fees, or miss your workout daily, or give up seven to nine hours of sleep, you make other choices. Some trade-offs impact work. People change careers. You see brilliant women stepping out of traditional ladders.

More people are reclaiming agency over how, when, and where they work. The pandemic blew doors wide open for structural change. Now hybrid work is common where it never was before. That's systems change resulting from people opting out, saying no, choosing different paths. Employers realized they had to rewrite rules to retain engaged workforces.

Haley Swenson: What's your main message for mothers reading this?

Leslie Forde: You won't like it—the answer is you have to do less. You can outsource if you can afford it. You can "spouse source" if you're partnered. You can eliminate things, leverage family, community, benefits, whatever money you have.

Most importantly, understand that if your goal is growth—and for many of us, especially in communities of color, from immigrant families, we don't want to just subsist—we want lives we're proud of, impact on the world's problems or people closest to us. If you're ambitious and want to honor that, you'll have to stretch in ways that don't always feel great, make trade-offs that don't feel great. But if you understand what the rules should look like for your life, you can choose your adventure and path.

The real work is understanding what causes stress we face—mental load, decision fatigue, time scarcity working together to take our brains apart daily—then finding interventions that work. Not every intervention works in every season, especially if you're single, have a special needs child, or are caring for a disabled adult. It's about having a toolkit to rebuild your life to reduce stressors while honoring your ambitions.