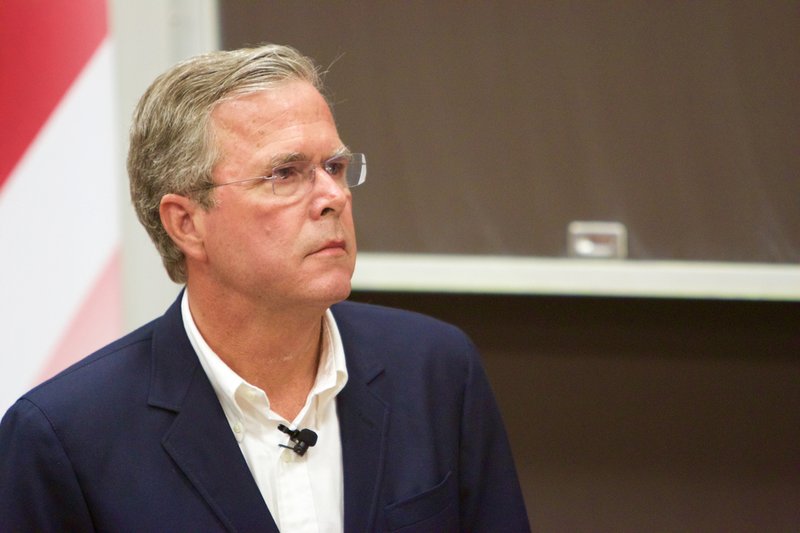

Would Jeb’s Education Plan Really Improve Access to High-Quality Pre-K?

Blog Post

Feb. 1, 2016

On the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, former Florida Governor Jeb Bush released his education plan, calling attention to education as “the civil rights challenge of our time.” Given Governor Bush’s focus on education reform during his tenure in Florida and his subsequent founding of the Foundation for Excellence in Education, it’s not surprising that he would be the first Republican nominee to release a plan. Bush’s plan spans from pre-K up through college and calls for significant changes to the existing system. His policies largely correspond with traditionally conservative ideals of limited federal involvement (including cutting the Education Department by 50 percent), parental choice, and the power of the free market.

Governor Bush’s plan calls for converting 529 college savings accounts into Education Savings Accounts that would allow families and individuals to save for any level of education, tax-free. While incentivizing families to save for their children’s futures is a sound proposal, families struggling to make ends meet often don’t have the resources to save for high-quality pre-K, K-12, or higher education, let alone all three. This recent US News and World Report article states that the median 529 college savings account size in Alabama is $6,500. This isn’t enough to cover even one year of schooling at any age in most states, and this amount is likely accumulated by parents over up to 18 years of savings before a child heads off to college-- not just the three or four years before they begin pre-K.

Bush’s plan offers a solution to jumpstart the Education Savings Accounts for low-income families: he would allow states to directly deposit $2,500 per year of federal funding into families’ Education Savings Accounts for children under the age of five in states that are willing to opt out of the existing 44 federal programs (a misleading number often referenced by Republicans) that currently support early education. This would essentially be a voucher that parents could use for the early education and care of their choosing. We have many questions about how this would work, but our two main concerns relate to access and quality.

There’s also the fact that those 44 federal programs pay for much more beyond early education. What would a state “opt-out” mean for Title I, IDEA Preschool Grants, or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF)? It’s also unclear what would happen to Head Start and Early Head Start, which provide comprehensive early education services to families below the poverty line, under this plan since they have a unique federal to local structure and operate relatively independent of the state. And, what about the fate of the federal Preschool Development Grant program that is now a part of the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)? That is also unclear under Bush’s plan. This grant program has played a key role in providing and expanding access to high-quality pre-K programs in 18 states.

Research shows that $2,500 is not enough money to provide high-quality pre-K, especially for working parents who often need access to full-day programs. According to NIEER, the average state spending on pre-K is about $4,100 per child per year. High-quality programs like New Jersey’s Abbott pre-K program cost over $13,000 per child. Bush explains that states, districts, and parents would be expected to supplement the cost of care, but he does not offer ideas on how this would work in a way that is effective and equitable.

After all, states and districts have varying track records of investing in early education. If a state chooses not to supplement this funding and the pre-K vouchers fail to cover the full cost of care, parents will be forced to cover the costs themselves. This would likely result in low-income families only being able to access poor-quality programs or no programs at all.

Governor Bush does have a plan for attempting to ensure quality. According to the plan, “Participating states would create and execute a plan for regulating, evaluating and holding providers accountable for high educational quality, and ensuring parents have critical information on program quality and outcomes,” but the plan makes no mention of additional funding being provided to states to help put such a plan into action. This type of state-level accountability system sounds similar to the Quality Rating & Improvement Systems (QRIS) that grew largely due to the federal Race to the Top -- Early Learning Challenge. Nearly every state has a QRIS in some phase of development or implementation.

Creating a voucher program to fund pre-K isn’t a novel concept. Thousands of children in Minnesota currently receive what are essentially vouchers to attend pre-K through the state’s Early Learning Scholarship Program. Minnesota families earning up to 185 percent of the poverty line can use the scholarships to send their children to school-based, center-based, or even home-based pre-K. In an effort to regulate quality, scholarships can only be used at child care providers that have been rated by the state’s QRIS, Parent Aware. The maximum scholarship amount is $7,500 for the highest rated programs. While much more generous than Jeb’s plan, it still is less than the average cost of full-day, center-based care in Minnesota. This program has expanded pre-K access and encouraged providers to improve their programs, but the scholarships fail to reach the vast majority of the state’s eligible children because of limited state funding. We address the benefits and downfalls of the state’s scholarship program more extensively in our recent paper, Building Strong Readers in Minnesota.

Since Bush’s pre-K plan is short on specifics, a better way to predict how a future President Bush might handle pre-K issues is to look more closely at his tenure as Governor of Florida. By this metric, Bush’s pre-K record is a mixed bag. In November 2002, Florida residents voted for a ballot measure requiring the state to provide universal pre-K for all four-year-olds at no cost to families. In response, the Florida Legislature began negotiations over a universal pre-K bill and Governor Bush signed the Voluntary Pre-Kindergarten Program (VPK) into law in January 2005. This free, universal pre-K initiative led to the most rapid expansion of state-funded pre-K in the country. The expansion was made possible by using the state’s existing private child care sector to provide services to over three-fourths of program participants, though public schools offered pre-K programs as well. Currently, VPK serves about 80 percent of the state’s four-year-olds, second only to Vermont and DC in terms of four-year-old access.

While Florida may be a leader when it comes to access, the state is not a leader in quality. Currently, Florida spends just $2,238 per child enrolled in pre-K compared to the national average of $4,125. A study conducted by the University of Virginia in 2014 concluded that the Florida program “lags behind on some key structural measures of quality.” For instance, VPK currently meets only three out of the ten items on NIEER’s checklist. Lead teachers in the school-year program are not required to have a bachelor’s degree and assistant teachers do not have to meet any educational requirements. Determining what the teacher qualifications should be is left to local districts, meaning in one district a BA and a teaching license could be required while in a neighboring district it is not. And while the length of the program is determined locally, most school-year programs only operate for three hours a day.

Pre-K needs to be both accessible and high-quality in order for children, families, and society to see the long-term benefits. Replacing a host of federal programs that serve varying populations with just $2,500 per child is unlikely to expand access to the type of quality early education that produces a high return on investment. While Governor Bush seems to recognize that access to pre-K is important, he does not seem willing to invest in the level of quality that would make the most difference for children, especially those from low-income families. The plan he puts forth would actually decelerate instead of accelerate progress in early education.