Ushering Bilingual Education for English Learners Through Uncertain Times

Blog Post

July 23, 2025

Bilingual education supports all students’ second language acquisition, literacy development, and academic achievement. The benefits of bilingual education hold particular promise for the nation’s 5.3 million students identified as English learners (ELs), yet many EL students lack access to bilingual programs. With the shrinking federal role, states and school districts have an opportunity to lead in implementing asset-based approaches to EL education, including expanding bilingual education.

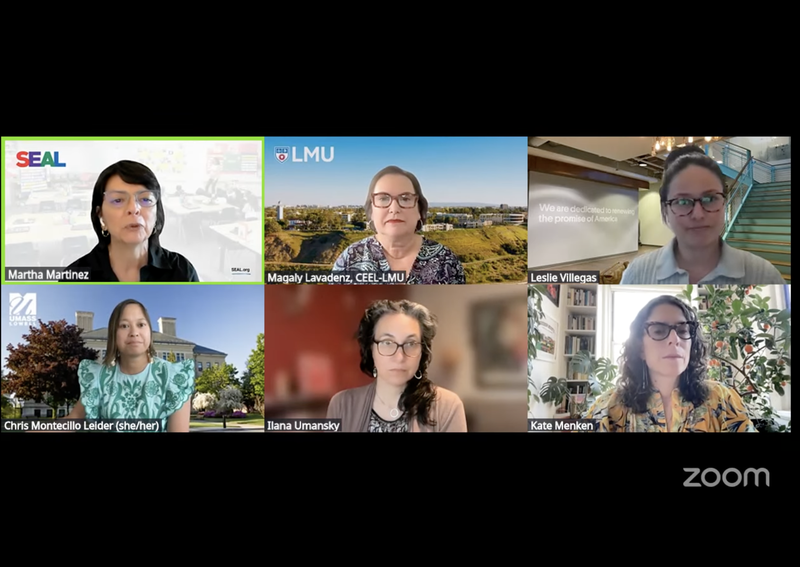

On June 25, 2025, SEAL and New America hosted a webinar with prominent EL and bilingual education leaders to reflect on the evolution of EL education in the U.S., unravel misconceptions about language education, and highlight the benefits of bilingual education for ELs. The webinar featured a panel discussion with bilingual education researchers and a moderated conversation with a school system leader about how they have utilized bilingual education to advance academic success for their students.

This conversation comes at a time when the federal government is dismantling federal supports for multilingual students and pushing an English-only agenda. Despite this retreat by the federal government, states and districts will have to continue to lead the way and ensure that the progress made in implementing asset-based approaches to EL education is not undone. As we look toward the future, here are some key lessons from the conversation to help us keep a focus on building a brighter tomorrow for English learners:

Remember the Past: Rooted in Civil Rights, Bilingual Education Has a Long History of Success for EL Students

Bilingual education has its origins in the civil rights movement of the 1960s and, as Kate Menken, professor of linguistics at Queens College of the City University of New York, shared, the Civil Rights Act (CRA) of 1964 was the first federal recognition that language can be a source of inequity in schools. The federal government responded to this recognition by adopting the Bilingual Education Act (BEA) of 1968 which officially mandated that services be provided in school to ensure ELs were able to learn English. And although the BEA does not exist in its original form today, EL students’ civil rights are still enshrined in a variety of legal protections. Thanks to these protections, ELs have a right to a free public education, regardless of immigration status, and must receive appropriate language support services to help them access grade level content and learn English in a developmentally appropriate timeframe.

In the time since these protections were established, bilingual programs have gained momentum and proliferated, particularly over the last 15 years. However, because state and local jurisdictions have the authority to design and choose the educational services they provide, bilingual education programs can vary greatly. This variability can include who can enroll, program duration, the balance between English and the partner language, who teaches the program and how they teach, and what the long-term goals of the programs are, said Ilana Umansky, associate professor at the University of Oregon. Although bilingual programs can take different shapes and forms, the research base—which dates back to the 1980s—on the relative effectiveness of bilingual programs is unwavering in showing that bilingual programs benefit all students, particularly ELs, when compared to English-dominant programs.

As Umansky shared, this robust body of work has found that EL students enrolled in bilingual programs perform better in English Language Arts, math, social studies, and science; are more likely to become proficient in English; have stronger outcomes in their home/heritage language; and are more likely to graduate with a regular diploma. Bilingual programs also help ELs develop a stronger sense of identity and self confidence, stronger connections to family and more intergenerational communication, and a greater sense of pride in their culture and connection to their heritage. In addition to these benefits, EL students educated in bilingual programs have been known to outperform their EL peers educated in monolingual settings. And bilingual programs have also been known to help meet the intersecting needs of English learners who may also have a disability.

Since its inception, the bilingual education field has benefited greatly from federal funding. As Professor Magaly Lavadenz shared, federal funding has allowed researchers and practitioners to investigate the effectiveness of these programs and foster a level of interagency collaboration to strengthen the connection between research, policy, and practice. However, this historical investment in the field’s research and development is being threatened by potential cuts to Title III of ESSA, as well as National Professional Development (NPD) and Institute of Education Sciences (IES) grants.

Consider the Present: A Patchwork of Program Access, EL Teacher Licensure and Training, and Funding

Despite the overwhelming evidence pointing to the benefits of long-term developmental bilingual education for ELs and rapid growth of bilingual education programs, many speakers remarked that the vast majority of ELs are in English-dominant educational programs. This may be a result of bilingual education being framed as an opportunity for English monolingual students to add a desirable skill that would boost their competitiveness in the workplace, as Professor Menken remarked. Although growing interest is great, increased demand has led to bilingual program seats being filled by monolingual students who see bilingualism as a “nice to have” rather than ELs who need these language support services. And as Menken commented, “language policy decisions are at times more political than they are pedagogical,” which means the students who may benefit the most may not be the ones prioritized.

Additionally, as Christine Montecillo Leider, assistant professor at University of Massachusetts-Lowell, shared, many ELs, including those in bilingual programs, are currently in classrooms with teachers who do not have robust and appropriate training to work with them. A 2021 study conducted by Montecillo Leider found that teacher licensure, credentialing, and training was inconsistent across the country and even states that offered an English as a Second Language (ESL) license or add-on endorsement could not guarantee that teachers went through the appropriate coursework or field experience to teach EL students. According to Montecillo Leider, “several states didn’t even have credentials for teaching in a bilingual education setting, and disappointingly, only about half of the states even had a credential specifically for teaching in bilingual settings.”

Unfortunately, recent funding cuts to education research means that further investigation into how to bolster the EL teacher workforce may not occur. For example, funding for a first- of-its-kind Center on English Learners and Multilingualism that Lavadenz and her team at the Center for Equity for English Learners (CEEL) at Loyola Marymount were leading was recently pulled. As a result, researchers and practitioners are concerned about the financial and knowledge voids that federal disinvestment of this magnitude could mean for bilingual education moving forward.

Plan for a Bilingual Future for All: Improving Program Access, Workforce Availability and Quality, and Funding Can Continue Without the Federal Government

The “gentrification of bilingual education”—as has been coined by Menken and her colleagues—is something that must be addressed moving forward as bilingual programs continue to expand. If we hope to “remain true to the original social justice aims of these programs,” as Menken stated, ELs’ access must be prioritized. This can be done by making sure that programs are started in neighborhoods and schools with high EL-enrollment, holding seats for EL students, and allowing rolling admissions for multilingual families who enter school at different times or miss the kindergarten deadline.

Families can also play a role in advocating for bilingual education programs. As Norma Camacho, assistant superintendent of K-12 education for California’s Azusa Unified School District (AUSD), shared, families interested in having their children educated in bilingual programs should start by reaching out to their school principal in writing to start the grassroots effort. In California, school districts must explore the viability of a bilingual program when 20 or more parents voice interest in starting a bilingual program. And several states, including Texas, Illinois, and New York, have mandates that require bilingual education be provided when a specific threshold of EL students is met. These types of policies can be harnessed by multilingual families seeking the benefits of bilingual programs for their multilingual students.

In terms of improving the state of EL teacher preparation and licensure, Montecillo Leider argued that we need to change the way we think about “robust and rigorous training.” The add-on nature of bilingual education endorsements means that credentials and training are restricted to currently licensed teachers—the majority of whom are monolingual. As a result, many bilingual people in linguistically rich communities, like migrants who come to the U.S. with teaching experience and education in their home countries, are excluded from these pathways. States and districts are creating pathways for multilingual community members to enter teaching through Grow Your Own efforts that seek to remove barriers and increase access into teaching for recent arrivals as well as former EL students.

And as the federal government continues to claw back its financial support for EL education services and research, Lavadenz called upon researchers and practitioners to seek out and build better relationships and partnerships—including with business and philanthropy—to help fill some of the gaps in funding and services for ELs during these tough times.

The superdiverse nature of the EL population across the country means that bilingual programs may not be viable in every context where EL students are enrolled. However, even when a full bilingual program for each language spoken is not possible, EL students can still be supported by intentional integration of their home language. As Umansky shared, all schools can support ELs by investing in community liaisons from their language communities, buying bilingual books, providing robust translation services for families, hiring teachers/aides that speak the languages spoken by students, and instituting “buddy systems” which pair EL students with each other.

As Camacho remarked, there continues to be a lot of work around addressing the deficit-based messages about language status and the different values attributed to some languages over others. The 90s and early 2000s were filled with negative messages that targeted Spanish-speaking communities, as well as policy and public discourse that bilingual education was failing students. Those messages still linger today. However, as Anya Hurwitz, executive director of SEAL shared at the end of the event, the power of the school to transform the culture and community for EL students and their families cannot be overstated, and lucky for interested parties, that work can continue to move forward regardless of the federal climate.

Link to resources shared during the event here.

Note: Although the event and this blog use the terms “bilingual education” and “bilingual programs,” these terms are intended to be interchangeable with “dual language education” and “dual language programs.”