Congress Uses July 2012 Student Loan Changes to Pay for Pell Grants

Blog Post

July 8, 2012

July 1st always marks the start of a new year for federal student loan rules. Any changes lawmakers make to the programs almost always affect only newly issued loans issued after July 1st of the year that those changes are put in place. This year that deadline received a lot of attention. After months of negotiating, Congress and the president finally agreed to extend the 3.4 percent interest rate on newly issued Subsidized Stafford loans issued as of July 1st, for the 2012-13 school year. But that’s not the only change to take effect.

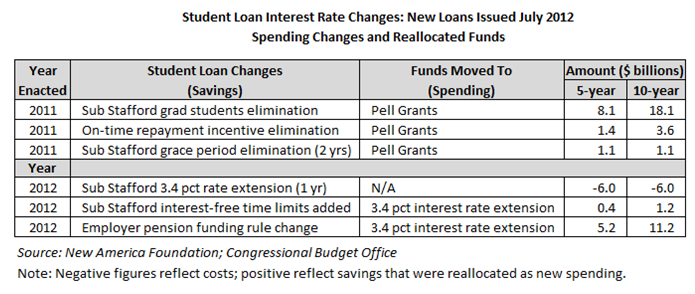

Last year, lawmakers made three other changes to federal student loans through two separate laws to create budget savings and provide additional funding for the Pell Grant program. Even though those changes were enacted in 2011, they affect newly-issued loans made on July 1, 2012 and after. While stakeholders were so focused on the interest rate extension, they probably forgot or didn’t realize that Congress made these other changes or why. The table below shows each change Congress made to federal student loans that took effect starting July 1st, 2012. It also shows the budgetary savings (or costs) associated with each change and how Congress reallocated those funds.

As is clear in the table, Congress and the president moved billions of dollars from student loan programs to Pell Grants in 2011. That funding is the latest step in Congress’s multi-year effort to provide supplemental funding for the program that started back in 2009 as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act.

In the 2011 Budget Control Act (aka the debt ceiling agreement) lawmakers made graduate students ineligible for Subsidized Stafford loans. Subsidized Stafford loans do not accrue interest while a borrower is in school or deferment and are provided to students who met a needs test. That law also ended a repayment incentive program under which the U.S. Department of Education would reduce the origination fee it charges on each loan (by 0.5 percentage points for Stafford loans and 2.5 percentage points for PLUS loans) so long as a borrower made a year’s worth of on-time payments. New loans will charge the full fee, which is 1.0 percent for Stafford loans and 4.0 percent for PLUS loans.

Then, late in 2011, lawmakers enacted the fiscal year 2012 consolidated appropriations act, which included the temporary suspension of the grace period benefit on Subsidized Stafford loans for undergraduates. Loans issued as of July 1, 2012 will begin accruing interest as soon as a borrower leaves school, instead of at the end of a six-month grace period. Oddly enough, this change applies to loan issued for the 2012-13 and 2013-14 school years, but the benefit is reinstated on loans issued after those years. The reason? Congress needed to cut benefits to generate budget savings, but it didn’t need the savings that would have come from a permanent repeal of the grace period benefit.

In 2012, the Congress and the president turned their attention away from the Pell Grant program to extending the 3.4 percent interest rate on some loans, which cost a total of $6.0 billion. Congress offset that cost via two changes. First, Congress enacted yet another change to the interest-free benefit on Subsidized Stafford loans. Newly-issued Subsidized Stafford loans will remain interest-free while a borrower is in school, but the benefit ends once a borrower is enrolled beyond 150 percent of the time it takes to complete his program. Additionally, Congress changed pension funding rules (unrelated to education policy) to cover the cost of extending the 3.4 percent interest rate for one year on Subsidized Stafford loans.

Two points are clear from this recap of changes to student loan programs. First, Congress has repeatedly gone after the interest-free benefit on Subsidized Stafford loans to help pay for the Pell Grant program and other student aid changes. So it is probably only a matter of time before lawmakers end the benefit completely for undergraduates.

That brings up the second point. Congress and the president twice last year moved funds from student loans to Pell Grants. But this year, they put money back into student loans, on net, but allocated no new funding to Pell Grants.

Square that decision with this fact: The Pell Grant program is on course to burn through all of the supplemental funding listed above by the 2014 appropriations cycle, which starts next year. It will need a fresh $6 to $8 billion to stave off a big cut to the grants it provides undergraduate students. Long-term planners your Congress and president are not.