Department of Ed Gets It Wrong on New Pay As You Earn Calculations

Blog Post

July 18, 2012

On Tuesday, the U.S. Department of Education proposed regulations for its new Pay as You Earn (PAYE) student loan repayment plan. The Obama Administration announced the new repayment option for federal student loans last year and the newly-released rules detail how it will work and who is eligible. But a quick look at the document reveals a few problems in how the Department is explaining this new program.

First, some background. The new Pay As You Earn plan adds to the two existing repayment options (Income Contingent Repayment, or ICR, and Income Based Repayment, IBR) that allow borrowers to pay back student loans based on their income. Under the existing IBR plan, borrowers who qualify for partial financial hardship – defined as having a loan payment higher than 15 percent of the borrower’s adjusted gross income after subtracting 150 percent of the household poverty threshold – make payments equal to 15 percent of their income minus the poverty threshold. The government forgives any remaining unpaid loan balance after 25 years.

Under a 2010 law, those numbers are set to change for new borrowers in 2014 and thereafter. Specifically, the 15 percent rate is cut to 10 percent, and unpaid loan balances are forgiven after 20 years rather than 25. The Administration’s Pay As You Earn plan effectively makes borrowers who took out an initial loan in 2008 and a subsequent loan in 2011 or later eligible for this plan immediately. (Technically, the Administration is using its regulatory authority to tweak the Income Contingent Repayment (ICR) plan to create the Pay As You Earn Plan.)

In the rules released this week, the Department provided an example of how the PAYE plan, which they say is more generous than the existing income based repayment system, would benefit a hypothetical borrower, Jesse. A table in the regulations illustrates Jesse’s life: he leaves school with $40,000 in federal loans, gets married, and has a child in his fifth year of work, with a second child born in his seventh year. The plan compares what Jesse would pay on his loans under the old IBR plan and the new PAYE plan. But this illustration is misleading on a number of counts.

Over the course of the 25-year illustration, the Department of Education never accounts for an inflationary increase in the poverty threshold that Jesse can claim when calculating his loan payment. This dramatically affects how much Jesse will pay every month because as the federal poverty threshold grows with inflation, Jesse can exclude more of his income each year in the IBR calculation.

In fact, over the last twenty years, the individual poverty exemption has increased at an average rate of 2.5 percent annually. Over that same period of time, the annual exemption for each additional member of a household increased at a rate of 2.6 percent. That means that by the 25th year of Jesse’s payment under the existing IBR plan, the size of the federal poverty exemption would have nearly doubled from his first year.

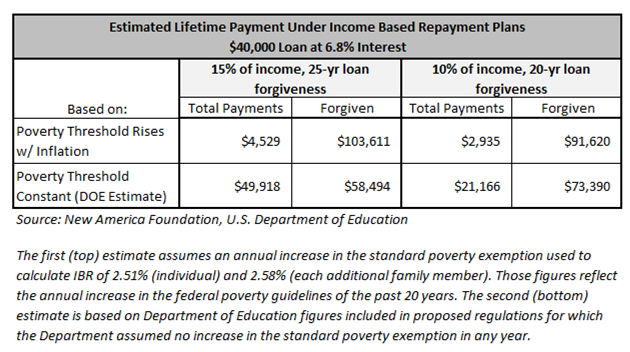

The table below shows how much Jesse would really pay, using all the same calculations that the Department uses, but making annual inflationary adjustments to the poverty exemption.

The table also illustrates something wholly absent from any of the Department of Education’s explanations of the benefits (and costs) of PAYE and IBR. Jesse is accruing interest on his loans faster than he is paying them off – meaning that his loan balance grows over time. In the end, he has a loan balance forgiven that is well over twice what he originally borrowed.

More importantly for Jesse, the inflation-adjusted poverty exemption means he will pay significantly less before he qualifies for loan forgiveness than the Department explains in its illustration. If Jesse made his loan payments under the existing IBR plan (linked to 15 percent of his income with 25-year loan forgiveness), he would pay a whopping $45,389 less than what the Department of Education shows. Under the proposed PAYE plan (tied to 10 percent of income with 20-year loan forgiveness) he would pay only $2,935 over the course of twenty years. That is $18,231 below the amount that the Department of Education shows in its illustration. Click here to compare our figures with those released by the Department.

Since the recently-released regulations are not yet final, we hope the Department will address both issues – the poverty exemption calculation and the swelling size of Jesse’s loan balance – in its subsequent release. The Obama Administration should be forthcoming about accrued interest and the actual amount of debt forgiven under IBR and PAYE, and its examples should reflect the inflationary increases in the poverty exemption that are required by law.

On a final note, the proposed regulations show the PAYE plan will cost taxpayers $2.1 billion over the next 10 years. That’s because the Department believes 1.67 million borrowers will be eligible for and choose the PAYE plan. Some 400,000 of them will get loan forgiveness worth an average of $41,000 on original loan balances of $39,500.

That is effectively a $41,000 grant. It is also four times more than what the average four-year Pell Grant recipient receives in grant aid. That is exactly the kind of number the Department of Education should be talking about.