The Jakarta Model Is No Blueprint

The Hidden Costs of Indonesia’s Industrial Policy

Blog Post

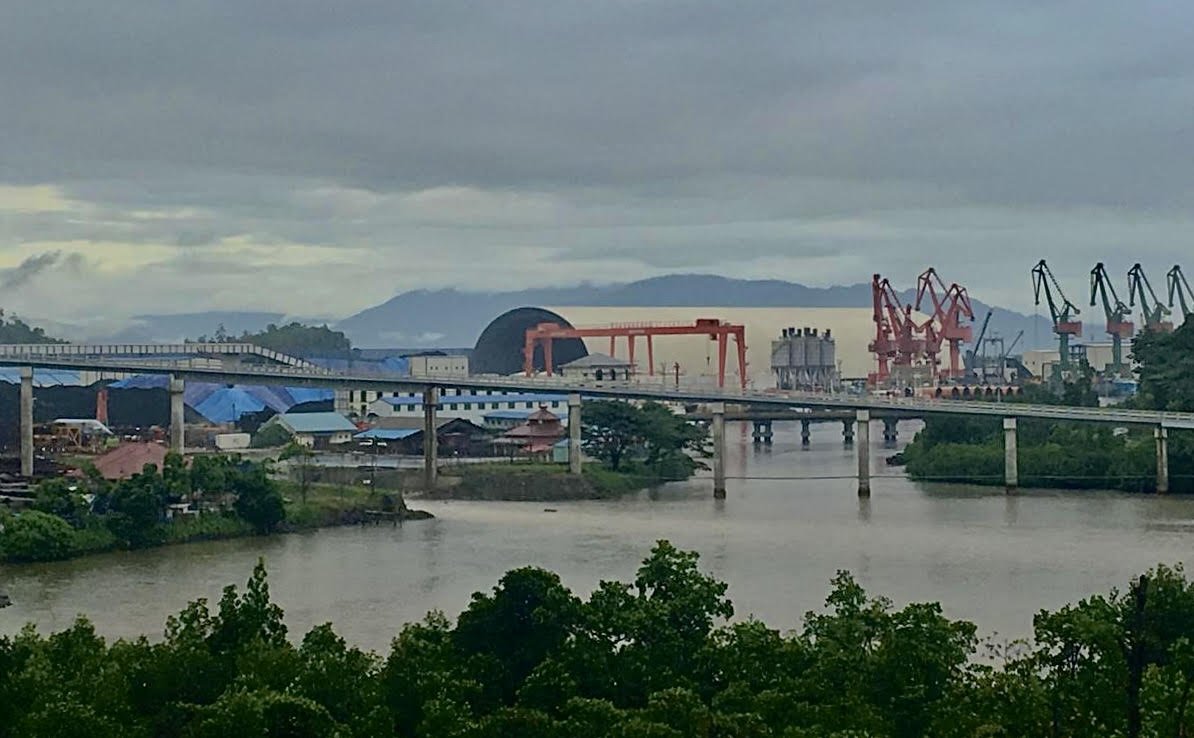

Virtue Dragon Nickel Industry, a major Chinese smelting company just south of IMIP in Konawe, Indonesia, was among many that benefited from the government's nickel export ban. Photo by Alvin Camba.

Sept. 11, 2025

This article is part of the Power Switch series, which explores the need for systemic changes to critical minerals production, geopolitics, and climate finance to empower the Global South in the clean energy transition.

At a Glance

- Behind Indonesia’s impressive economic growth lie the uncounted costs of air pollution, tailings waste, rising cancer rates, and the destruction of vital ecosystems, resulting in a fundamentally distorted picture of the country’s booming mineral refining industry.

- Across Indonesia’s eastern archipelagos, three massive industrial parks that have drawn more than $100 billion in mainly Chinese investments have contributed to mudslides, contaminated farm fields and marine ecosystems, skyrocketing rates of asthma and pulmonary disease, and widespread labor abuses.

- A New America analysis finds that the hidden human and environmental costs of Indonesia’s industrial expansion total more than $2.75 billion, enough to substantially offset revenue gains from the country’s nickel exports.

- Indonesia’s industrial parks systematically redirect costs to farmers, fishers, and workers who are left with toxic water, sick children, and unstable land—not as isolated cases of regulatory failure but as features of a model that prioritizes industrial expansion above all.

- Indonesia’s nickel boom and its consequences show that sustainable growth cannot be built on silenced communities and poisoned land; it requires strong civic voices, wider climate finance, and real accountability.

Surging global demand for clean energy has pushed mineral extraction to unprecedented levels. Since 2017, lithium production has doubled and nickel mining has rapidly expanded. As home to the world’s largest nickel reserves, Indonesia has positioned itself at the center of this boom, making Jakarta an increasingly attractive model for resource-based industrialization for policymakers across the Global South. Leaders of countries such as Namibia and Nigeria have praised Indonesia’s decision to ban raw mineral exports and require domestic refining—and are emulating it. Zimbabwe’s Vice President, Kembo Mohadi, cited the Asian country’s strategy as “inspiring and educative,” linking it to the African Union’s Africa Mining Vision. Declaring that minerals must no longer be exported without local value addition, Nigeria’s Minister of Solid Minerals insisted: “You must start a factory to produce something that is associated with the mineral that you are taking out.”

On the surface, Indonesia’s story is compelling: It has grown from a raw commodity exporter to a dominant refiner in global battery supply chains, creating jobs and generating billions in revenue. Indonesia’s approach—or the so-called Jakarta Model—has indeed yielded macroeconomic benefits, but beneath the headline success lies a troubling reality of sacrifice zones, corporate impunity, and environmental devastation, raising a critical question: Is Indonesia worth emulating?

Under former President Joko Widodo, widely known as Jokowi, Indonesia implemented a targeted mineral export ban and offered generous incentives to foreign investors in smelting and refining, focusing on Chinese firms that dominate these segments of the supply chain. The Indonesian government offered these Chinese companies a quasi-monopoly over domestic nickel in exchange for long-term investment in refining facilities. According to a former Ministry of Trade official, the export ban, which prohibited the overseas shipment of unprocessed nickel ore, was the key policy instrument. Previously, most Indonesian nickel was refined in China, but the ban created a domestic market structure that gave Indonesian-based smelters and refiners exclusive access to the raw material. In 2014, Indonesia’s national smelting capacity was only 0.1 million metric tons; by 2025, it had skyrocketed to 22.9.

The policies generated a financial windfall for Indonesia’s government and elites. Between 2013 and 2023, nickel export revenues soared from $6 billion to nearly $30 billion. Indonesia produces half the world’s mined nickel, and much is now processed domestically for use by companies like Tesla, Ford, and Volkswagen in electric vehicle batteries. The country also began producing battery-grade nickel sulfate in 2023, and its stainless steel production that year amounted to more than 4 million metric tons.

Jokowi’s policies produced four sprawling industrial parks linking extraction to smelting; this analysis focuses on three that have come at a steep human and environmental cost. Indonesia’s captive coal-fired power capacity, primarily serving metal smelters such as those used in nickel processing, has nearly tripled since 2019 to about 16.6 gigawatts across 130 captive plants. By 2021, the manufacturing sector contributed roughly 23 percent of the country’s carbon dioxide emissions, pointing to one unintended adverse consequence of the Jakarta Model.

The Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park in Morowali, Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, in May 2024. Photo by Alvin Camba.

Source: Alvin Camba

In Central Sulawesi, air and water pollution from the Indonesia Morowali Industrial Park, known as IMIP, have led to asthma outbreaks, and experts warn that prolonged exposure to industrial emissions may increase the risk of serious health conditions, including cancer. Local communities report being displaced, denied access to clean water, and left with unusable farmland. In the areas surrounding the Indonesia Weda Bay Industrial Park in Halmahera, known as IWIP, fishing stocks have collapsed as nickel tailings and industrial runoff have choked marine ecosystems, and residents are grappling with food insecurity and skyrocketing rates of respiratory illness. Similarly, Kalimantan Industrial Park Indonesia, known as KIPI, has transformed swaths of forest into bauxite pits, releasing red mud into rivers and contaminating indigenous Dayak land.

A Mutually Reinforcing Triangle

With a gross domestic product of $1.4 trillion, a population of 281 million, and a median per capita income of $5,509, Indonesia aims to become a top-five economy by 2045. Its industrial parks reflect a strategic coordination of capital, elite interests, and policy design. These ventures secured preferential access to domestic raw materials, often at government-mandated prices lower than global market rates. While the intent was to capture more value domestically, this also locked in exploitative practices. Interviews with mining companies in 2021 reveal that oversupply and lack of competition have reduced the real price of nickel ore in Indonesia to as little as $15 per wet metric ton, far below the official benchmark.

The political economy of the Jakarta Model is one of elite consolidation. Business leaders, political incumbents, and foreign investors form a mutually reinforcing triangle that is scaffolded by Indonesia's powerful military. National leaders from Jokowi to his successor, President Prabowo Subianto, tout the parks as proof of economic progress. At the same time, business elites trade campaign donations for priority access to processing licenses, guaranteed feedstock supply agreements, or expedited approvals for land use and investments within industrial parks. Local governments in Sulawesi issue land use permits that let large mining firms overtake smaller artisanal miners, fueling deforestation, waste dumping, and community dispossession. While Chinese firms bring capital and technology and Western companies reap the processed outputs, Indonesians are left with precarious labor markets, dangerous working conditions, and broken promises.

Indonesia has laws that ostensibly mediate these harms, including the AMDAL environmental assessment system, post-mining land reclamation mandates, and water quality reporting statutes, but their enforcement is weak and highly politicized. Since the 2020 Omnibus Law, which centralized permitting authority in the hands of the national government, regional governments have had little say in approving or rejecting environmentally risky projects. Investments designated as National Strategic Projects can bypass environmental regulations entirely. When violations are found, consequences are rare. Regulatory capture by the refining and smelting sectors, conflicting mandates from local governments and the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, and the systematic marginalization of the Ministry of Environment and Forestry have severely weakened environmental oversight.

A Boom's Hidden Costs

IMIP, IWIP, and KIPI are vast, self-contained industrial parks that function as modern sacrifice zones where environmental and social costs are concentrated for economic gain. The large, vertically integrated parks house coal-fired power plants, smelters, refineries, workers’ barracks, hotels, airports, ports, and offices—all within self-contained zones where tens of thousands of workers operate across thousands of hectares. Adjacent to each park are mining concessions, often co-owned by Indonesian and Chinese firms, which supply raw minerals to the processing sites. IMIP, located on an island northeast of Java at the heart of Indonesia’s eastern region, was the flagship project and has drawn an estimated $34.3 billion in investment, primarily for nickel processing and EV battery materials. IWIP, in North Maluku, a remote island province to the east, is a geographic replica of IMIP, attracting around $11 billion in similar investments. KIPI, meanwhile, on the island of Borneo, represents a dramatic scale-up. With a price tag of $132 billion, it is the largest of the three parks and signals a shift from nickel alone to a broader portfolio that includes aluminum and so-called green energy production. These parks are not just industrial hubs; they have become economic anchors in their respective regions, attracting infrastructure investment, skilled labor, and political attention.

In 2022 alone, at least 21 incidents of flooding and mudslides were recorded in the Morowali region surrounding IMIP, a dramatic increase over the annual average of just two or three before the nickel export ban took effect. The captive-coal power plants providing energy to the parks reinforce Indonesia’s position as one of the world’s top carbon emitters. Coal fly ash, which comes from nickel waste and contains two to 10 times higher concentrations of heavy metals than does coal, has contaminated farm fields and marine ecosystems with heavy metals and organic pollutants. Health impacts have been especially acute in villages around IMIP, including Fatufia and Labota, where 40 percent of children under five suffer from asthma and adult pulmonary disease rates have risen by 25 percent in areas close to smelters, according to a community health survey conducted by the author. With clean water becoming harder to find, residents increasingly depend on polluted wells. Independent fieldwork conducted by the author in IMIP in 2023 showed that clinics, overwhelmed by the dual burden of caring for long-time residents and incoming migrant workers, are ill-equipped to handle the escalating crisis.

Photo: The author, center, conducting fieldwork with a research team in IMIP, 2019. Photo courtesy of Alvin Camba.

Source: Alvin Camba

Set amid coastal communities, the IWIP complex presents a different but equally troubling picture. Iconic diving and fishing zones in the area have deteriorated since 2018, undermined by thermal pollution from coal plants, oil slicks, and discharges from smelter facilities. Fishers in Gemaf kampung report that daily catches have dropped precipitously, and the waters have taken on a reddish hue. The Sagea River, once a vital freshwater source, now runs brown year-round. Fishers must travel farther, spend more, and risk more, only to return with less.

Meanwhile, respiratory diseases have surged. Cases of acute respiratory infections (ARI) in Central Halmahera Regency reached 6,581 between 2022 and 2024, a spike believed to be linked to IWIP’s nickel downstreaming activities. Data from the Lelilef Community Health Center further shows that the number of ARI patients in the Weda Tengah mining area rose dramatically from 434 in 2020 to 10,579 in 2023. Some patients experienced repeated infections, requiring multiple hospitalizations. Beyond ecological devastation, IWIP has sparked a wave of land grabs and displacement. Forests long stewarded by Indigenous communities are now occupied by nickel firms, many of which use coercion or exploit legal loopholes to acquire land. In an interview, one agriculture worker shared how his 38-hectare plot was taken without warning or compensation. It was not an isolated case. Between 2018 and 2022, over 5,331 hectares of rainforest were cleared in Central Halmahera for nickel mining with devastating consequences: degraded soil, clogged rivers, and intensified flooding. In 2023 alone, flash floods displaced at least 1,726 people in the region. Communities have had to dig wells or buy water as natural springs dry up or become too polluted to use.

KIPI has been marketed as the centerpiece of Indonesia’s green transition, yet its environmental footprint tells another story. Bauxite extraction, which strips topsoil and forest cover at massive scale, is carried out through longstanding open-pit mines that will be incorporated into the park as it evolves. In the initial implementation phase, KIPI used 9,866 hectares of land, and there are plans to expand it by 16,400 hectares. These clearances have led to dramatic sedimentation in rivers and streams, choking aquatic life and flooding adjacent farmland. Red mud, a highly toxic byproduct of the Bayer process used to extract alumina from bauxite ore, is often stored in unlined ponds, allowing heavy metals to leach into surrounding soil and water. Community health workers in villages around KIPI reported an increase in respiratory infections since 2020, with anecdotal reports of rising skin ailments, though no publicly available official record has documented these figures.

Fortescue, an Australian mining company that has collaborated with Chinese firms on other projects, has proposed studying the construction of a hydrogen and ammonia complex that would extract vast volumes of water to power its production of aluminum ingots, which are intended for global markets and may also eventually be shipped to Sulawesi to supplement its own alloy production. KIPI is increasingly evolving into a hub that not only receives raw materials from sites like IMIP and IWIP, but also processes them into semi-finished goods such as aluminum for EVs. The aluminum produced here, mostly flat-rolled and used for sheets, roofs, and battery casing, is exported in large quantities to firms like Tesla and major Chinese companies like BYD and CATL.

Labor exploitation is central to the three parks’ existence. Tens of thousands of Indonesians, many from the country’s densely populated areas, have migrated to the parks in search of work. Today, more than 250,000 laborers are employed in and around them, according to a member of NUGAL Ecological Indonesia, a civil society organization dedicated to promoting transparency in government and private sector projects. Rights groups paint a bleak picture of workers denied rest and adequate protection while logging excessive overtime, who are frequently silenced when they raise concerns. Attempts to organize are met with intimidation, and oversight remains minimal.

Based on publicly available data on fatalities, injuries, health impacts, and unresolved land disputes, the estimated hidden costs of Indonesia’s industrial expansion total more than $2.75 billion. The costs were calculated using standard metrics from public health, labor compensation, and environmental valuation frameworks commonly used in Indonesia and Southeast Asia and based on NGO reports, government disclosures, and investigative journalism. Comprehensive data on these socio-environmental harms remain limited or deliberately obscured, but the actual human toll is almost certainly far higher. Below, the estimated costs are broken down by category.

A Blueprint for Extractivism

The Jakarta Model shows how resource-rich countries can attract investment and climb the value chain—but at immense cost to people and the planet. Without key changes, it risks becoming a blueprint for a new era of green extractivism across the Global South.

Civil society must be given more than token space. Groups like the Jaringan Advokasi Tambang (JATAM), a grassroots network that documents the impact of industrial mineral processing on local communities, have played a vital role in amplifying local voices in Indonesia by documenting abuses ignored by state regulators. Including local advocacy organizations like JATAM in global critical-mineral forums would help counterbalance state and corporate narratives that present the Jakarta Model as a win–win. International climate finance must also widen its remit. The Just Energy Transition Partnership, for instance, has trained its sights on coal-fired power, yet it has been selectively silent about the captive coal plants and smelters that underpin the nickel boom. Without addressing the root cause, Indonesia’s emissions will continue to rise, despite donors claiming progress.

The flow of money is another lever. Development banks, sovereign lenders, and the carmakers that buy Indonesia’s nickel all profit from today’s arrangements. Conditioning loans and contracts on clean air, safe labor, and Indigenous land rights would force financiers and buyers to reckon with the true costs of their supply chains. At home, Jakarta itself must think beyond nickel. As in South Africa, mining rents could be used to seed a sovereign wealth fund and invested in sectors such as sustainable agriculture, ecotourism, and small-scale manufacturing—industries that can provide jobs without hollowing out communities.

Unless these steps are taken, Jakarta will cease to be a model and instead become a warning. The danger is not simply that the land and people of Morowali, Kalimantan, and Halmahera will continue to bear immense costs, but that Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Nigeria will replicate Indonesia’s mistakes under the banner of value addition. What is billed as a green transition will then be little more than extractivism by another name.