The “Great Questions” Leading to Community Connection in Austin, Texas

Brief

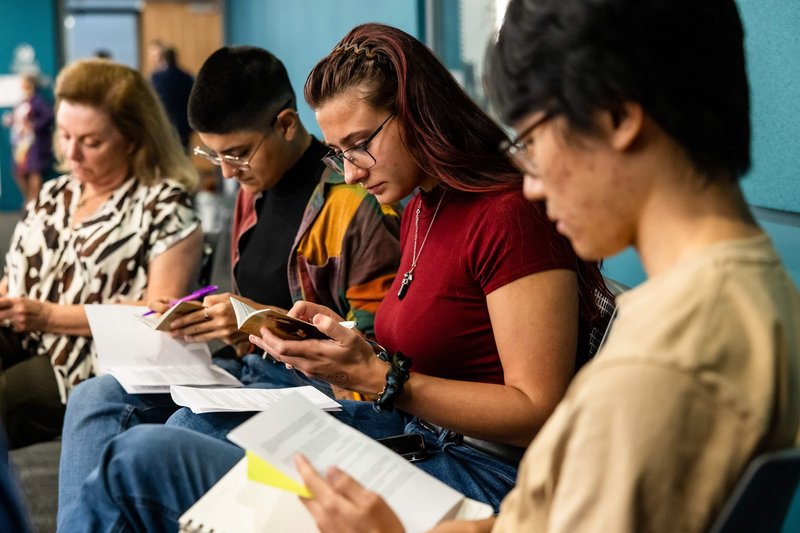

Photo courtesy of Catalin Abagiu/Austin Community College District. Used with permission.

Jan. 27, 2026

Introduction

Collaborative governance—or “co-governance”—offers a model for shifting power to ordinary people and rebuilding their trust in government. Co-governance models break down the boundaries between people inside and outside government, allowing community residents and elected officials to work together to design policy and share decision-making power. Cities around the world are experimenting with new forms of co-governance, from New York City’s participatory budgeting process to Paris’s adoption of a permanent citizens’ assembly. More than a one-off transaction or call for public input, successful models of co-governance empower everyday people to participate in the political process in an ongoing way. Co-governance has the potential to revitalize civic engagement, create more responsive and equitable structures for governing, and build channels for Black, brown, rural, and tribal communities to impact policymaking.

Still, co-governance models are not without challenges. The hierarchical and ineffective nature of our current governing structure is difficult to transform. Effective collaboration between communities and politicians requires building lasting relationships that overcome deep distrust in government. So far, effective models of co-governance tend to be local and community-specific—making it critical that we share stories of success and brainstorm ways to scale.

For this interview, New America’s Hollie Russon Gilman and Sarah Jacob spoke with Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr., associate professor of government at Austin Community College (ACC) and founder of the Great Questions Project, on how schools can serve as a place of productive dialogue and how that’s being done through the community seminar model at ACC. To read more of the Political Reform team’s explorations of co-governance in practice, see the project page.

Q&A with Ted Hadzi-Antich Jr.

What is a community seminar?

The community seminar is something we’ve been running for four years now. It’s a co-curricular event that supports our Great Questions courses, though any student is welcome to attend—you don’t have to be enrolled in one of those classes. The idea is to bring people together for an evening of discussion about persistent human questions, guided by transformative texts, authors, and ideas.

In the past, we’ve discussed works like the Book of Genesis and the Qur’an, exploring questions such as: What are humans? Where did they come from? And why does it matter? One of those sessions went so long that campus police eventually shut it down because we were still talking long after the building had officially closed.

Participants are mostly students. We always have some community members, but they’re a small percentage, maybe 5 or 6 percent.

The way the seminars work is that students have a required reading before attending. In post-event surveys, students consistently report that they’ve done at least some of the reading, which helps them feel ready to engage. After RSVPing, they receive an email with the event location. When participants arrive, they get a note card with a color that assigns them to a small discussion group of about 10 to 12 people.

Each group has a facilitator, either a faculty member from the Great Questions program or a student leader. In fact, at our most recent seminar, most of the facilitators were students.

Can you walk us through your most recent community seminar?

The focus of this latest community seminar was the question, “What is an American?” Students read the Declaration of Independence and excerpts from authors such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Abraham Lincoln, Frederick Douglass, Barbara Jordan, Harvey Milk, Gloria Anzaldúa, and Samuel P. Huntington.

Huntington’s quote at the end of the reading packet really resonated: “Critics say that America is a lie because its reality falls so short of its ideals. They are wrong. America is not a lie; it is a disappointment. But it can be a disappointment only because it is also a hope.” I love that—it captures the contradictions of America so well. The United States has always been about striving toward ideals that are, frankly, radical in human history: that all people are created equal. That’s not something many civilizations have dared to put at the center of their founding principles. And during the seminar, students wrestled with what that means today—and what responsibility they have to live up to that hope.

Some expressed cynicism, saying democracy isn’t working right now and that maybe we need something stronger. Others pushed back, reminding the group that our democratic principles have helped us overcome enormous challenges in the past.

One of the guiding questions was drawn from Frederick Douglass: The principles of the Declaration are saving principles. How do these principles save? How might they still be saving today? That sparked incredible discussion about how timeless ideals can guide us through modern political and social challenges.

This particular seminar was also unique because we invited elected officials to participate—not as speakers or leaders, but simply as fellow participants. We had members of the Texas State Legislature, the Austin Mayor Pro Tem, the Mayor of Cedar Park, county commissioners, and district court judges.

We did wish there had been a bit more partisan diversity, but since we’re in Austin, most participants leaned progressive. Still, having officials in the room alongside students was powerful. One chief of staff asked a thought-provoking question: He works for a progressive Democrat in a conservative state and said, “I often have to collaborate with colleagues whose policies I deeply disagree with. How far can someone go before I can’t talk to them anymore—especially when not talking means I can’t help my constituents?” It opened up a deep conversation about compromise and communication in politics.

Elected officials later told us they learned a lot about their constituents by participating in a nonpartisan, reflective conversation—not a policy debate, but a dialogue about identity and belonging. And students said the same—they appreciated hearing directly from people in public office.

In your community seminar conversations, did you see discussions that felt uniquely Austin or uniquely representative of Austin Community College?

Well, I don’t know if it was uniquely Austin, but it might’ve been uniquely Texas. Maybe it’s just that border-state perspective. We have a lot of first-generation students from Mexico, so when we talk about immigration and American identity, that conversation hits differently for students whose parents were born in another country—or for students who came here as babies and now face questions like, “Am I an American?”

There’s an intensity there that’s very different from talking about these issues in the abstract. So I think that aspect—the presence of so many first-generation students—was somewhat unique. But then again, there are first-generation college students all over the country.

In Texas, the concentration might be higher, and many students come from Mexico or Latin America. But if you were in Iowa, you might also have many first-generation students, just from different backgrounds. Or if you were in Michigan, in a place like Dearborn, you might have a lot of first-generation students from the Middle East.

So, I don’t know if it’s uniquely Austin. That’s just what comes to mind. We didn’t really talk much about Austin itself—it was more about larger ideals. Federal politics came up a bit, but the focus was broader.

Source: Photo courtesy of Catalin Abagiu/Austin Community College District. Used with permission.

What’s made it possible to host events like this? What have you had to problem-solve, or how have you adapted the model to make it practical?

This all grew out of me and my colleagues just wanting to make it happen. We’re getting more institutional support now, in terms of logistical help. And we’ve made a lot of changes since we started about four years ago. The structure of the discussion guide has been tweaked a lot, and we do an evaluation after every seminar.

We also found a clever way to boost participation, as many students get extra credit for attending. We encourage professors to offer that if it works for them, and it really helps get students through the door. To receive extra credit, students have to complete an evaluation form. They scan a QR code, fill out the survey, and then receive an emailed confirmation of attendance.

That system gives us a great response rate. For the last community seminar, about 150 people attended, and 60 completed evaluations.

And we really pay attention to that feedback. Early on, people said they had a hard time participating because a few people dominated the conversation—there are always two guys who won’t stop talking. So, we added more structure, borrowing from classroom practices.

Originally, there were no moderators—it was just an open conversation. Now, we have designated discussion leaders, which has been really helpful. To my knowledge, we’ve never had a situation where someone had to step in and tell a participant they were out of line. I’m sure that could happen someday, but so far, it hasn’t.

The event itself is very organic. I manage an email list built from RSVPs, and I invite people to bring friends, spouses, or kids. It’s really community-driven.

I’ll usually announce an event about a week in advance, and RSVPs start rolling in. I know roughly half of the people who RSVP will actually show up. So, if 300 say yes, I expect around 150 in the room.

I reach out to faculty and students who can help moderate. Some say yes and actually show up, others don’t, but it always comes together. People often offer to help on the spot, and we just say yes and hand off tasks. Things may not go exactly as planned, but they often turn out even better.

At our last event, we suddenly needed to create two more discussion groups and didn’t have enough note cards, so someone improvised a new system on the fly. Later, I saw photos of a group I didn’t even know existed—they had just set up and started talking!

In that sense, the event itself is kind of democratic. People see problems and solve them together. Tocqueville would love it—it’s that local, collaborative spirit in action.

We also serve food beforehand. People sit with strangers, talk, and settle in. It might look effortless, but there’s a lot of intentional “vibe-setting.” We want everyone to feel comfortable, calm, and free to be themselves. To say things others might disagree with, and to hear things that challenge them.

If someone wanted to replicate this model, how would they go about that?

We’ve got a ton of material available on our website, and our nonprofit—the Great Questions Foundation—actually supports this work. The Foundation typically provides food for the Austin event. In fact, the Great Questions Foundation partly exists because it was so hard for us to find a food budget for these gatherings. We finally said, “You know what? Let’s start a nonprofit.”

Of course, that nonprofit quickly took on a life of its own, and now we’re doing national projects with hundreds of faculty members.

If there’s a faculty member out there interested, ideally, two or three people could collaborate on it together. Tell them to reach out to me, and I’d be happy to have a conversation about what that could look like.

If they’re serious, we could even send someone to their campus to help get the first event off the ground. And if your organization wanted to support us in that effort, that could be very helpful as well. It could be an interesting initiative to get more colleges involved in hosting community seminars. It’s really not very expensive, especially if you already have the space.

What stands out to you most about the conversations that happen in these seminars?

The diversity in the room made these discussions especially rich. Community colleges are unique that way—you get an incredible cross-section of America: veterans, formerly incarcerated people, single parents, working adults, first-generation students. You won’t find that range of lived experience at places like Stanford or Yale.

And while we did offer pizza, people clearly came for the conversation. It’s rare these days to be in a room with people who think differently from you. We tend to live in echo chambers with our social media feeds and friend groups that reflect our own perspectives back at us. But here, you might expect someone to be progressive, and then they’ll surprise you with a very conservative take on education. It reminds you that people are complex and that they contain multitudes.

That’s what makes the community seminar so special. It’s a space where people come together to listen and talk openly. There aren’t many rules, and when I welcome everyone, I just say, “Be cool to each other. You all know what that looks like.”