The Alliance Dividend: How NATO’s Factory Floor Revival Is Rewiring Transatlantic Power

Brief

Pfc. Brent Lee via U.S. Army

June 24, 2025

At a Glance

- NATO weapons production has catalyzed a transatlantic defense industrial revival, reawakening American factory towns while gradually rebalancing European defense procurement.

- Employment data from defense manufacturing hubs reveals how weapons contracts have reversed decades of decline in American communities, but also exposes new vulnerabilities in transatlantic defense supply chains.

- The United States and Europe must reconcile divergent approaches to defense industrial policy to build a resilient security architecture before threats from Russia materialize.

- Political volatility threatens this revival: Trump’s temporary aid suspension in March 2025 demonstrated how quickly policy shifts can disrupt the defense-dependent communities that are integral to transatlantic security.

As NATO leaders gather in The Hague this week for their annual summit, the focus is on politics as usual: burden-sharing, Ukraine’s stalled membership, European autonomy, and the alliance’s fate under a resurgent “America First” agenda that has found the United States embroiled once again in a Middle East war. U.S. President Donald Trump has succeeded in convincing most alliance members to spend 5 percent of GDP on defense. Days before the conference, some clever wordsmithing and diplomatic sleight of hand produced a compromise communique. The language artfully shifted from “we commit” to “allies commit,” allowing Spain to argue that the spending pledge does not apply to all NATO members while permitting the alliance to claim unanimous agreement on the summit statement.

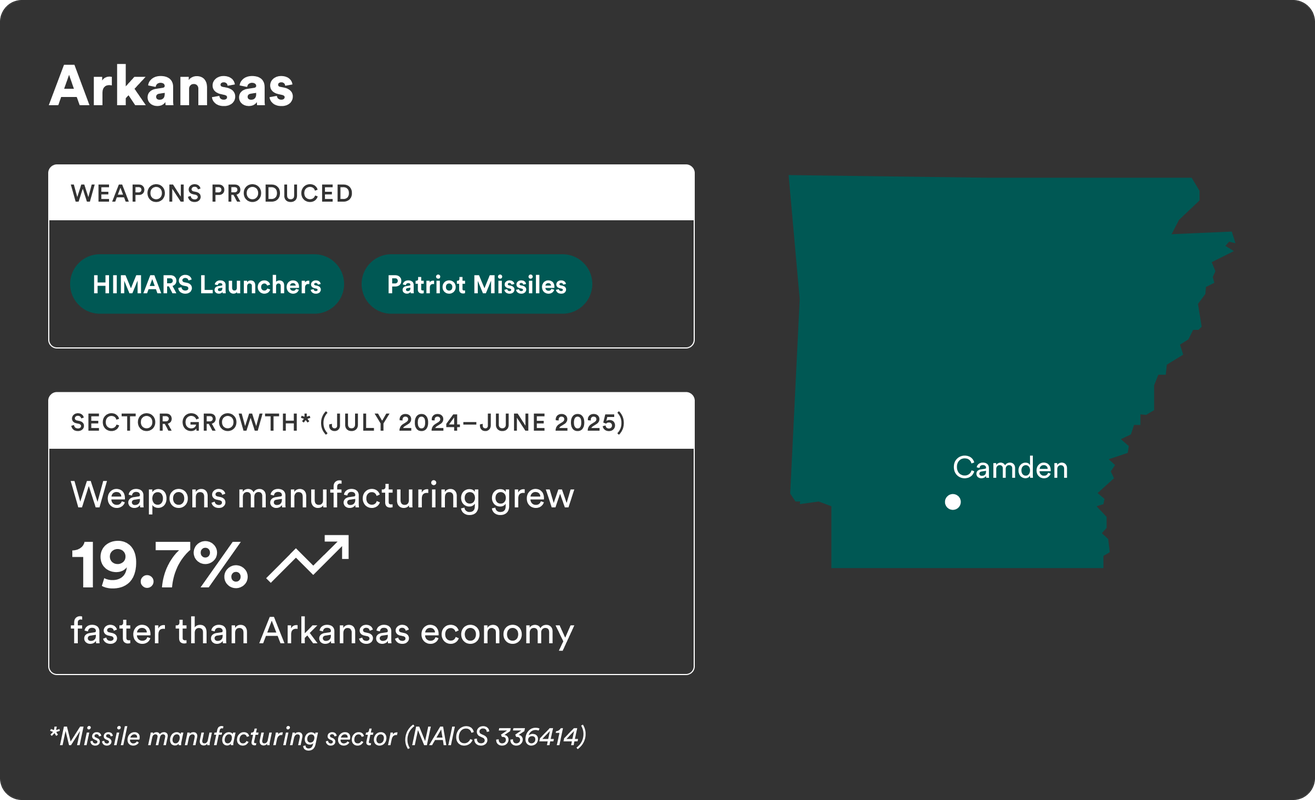

While NATO’s future is dissected in The Hague, in Camden, Arkansas—4,600 miles and a world away—the verdict is already in. The economy is roaring back to life. The alliance may be fracturing at the top, but on the ground, in the town where American-made High Mobility Artillery Rocket System (HIMARS) launchers are built, its logic is simple: Contracts roll in, missiles roll out, and the jobs keep coming. It is a strange twist: The same alliance that France’s President Emmanuel Macron declared “brain dead” in 2019 is now resuscitating communities once left for dead—reviving not only arsenals, but the political promise of steady work in an age of strategic uncertainty. In a world drifting toward disorder and defined by grey zone conflict, the muscle memory of Cold War mobilization is returning—in steel, in silicon, and in payrolls.

“In a world drifting toward disorder and defined by grey zone conflict, the muscle memory of Cold War mobilization is returning—in steel, in silicon, and in payrolls.”

Camden is not an outlier—along with other defense manufacturing towns, it’s a frontline in NATO’s industrial reawakening. The roughly $67 billion in U.S. military equipment to Ukraine since Russia invaded in 2022 is one reason for that revival, catalyzing a wave of defense production that has revved up dormant supply chains and trained a harsh spotlight on the question of transatlantic industrial resilience amid depleted stockpiles. There’s broad agreement in Washington, London, and Brussels that change is overdue to keep pace with threats from Russia and China. But as governments argue over how much to spend and where, a more urgent question cuts through the noise: Will all this investment—no matter the final number—deliver the political cohesion and industrial resilience the alliance now needs to survive?

The real fault lines in NATO aren’t about percentages. While leaders haggle over targets, the ground beneath the alliance is shifting. What’s reshaping NATO isn’t budget spreadsheets—it’s a manufacturing surge sparked by the war in Ukraine. An unplanned industrial revival is retooling the West’s defense base and rewiring the alliance from the factory floor up.

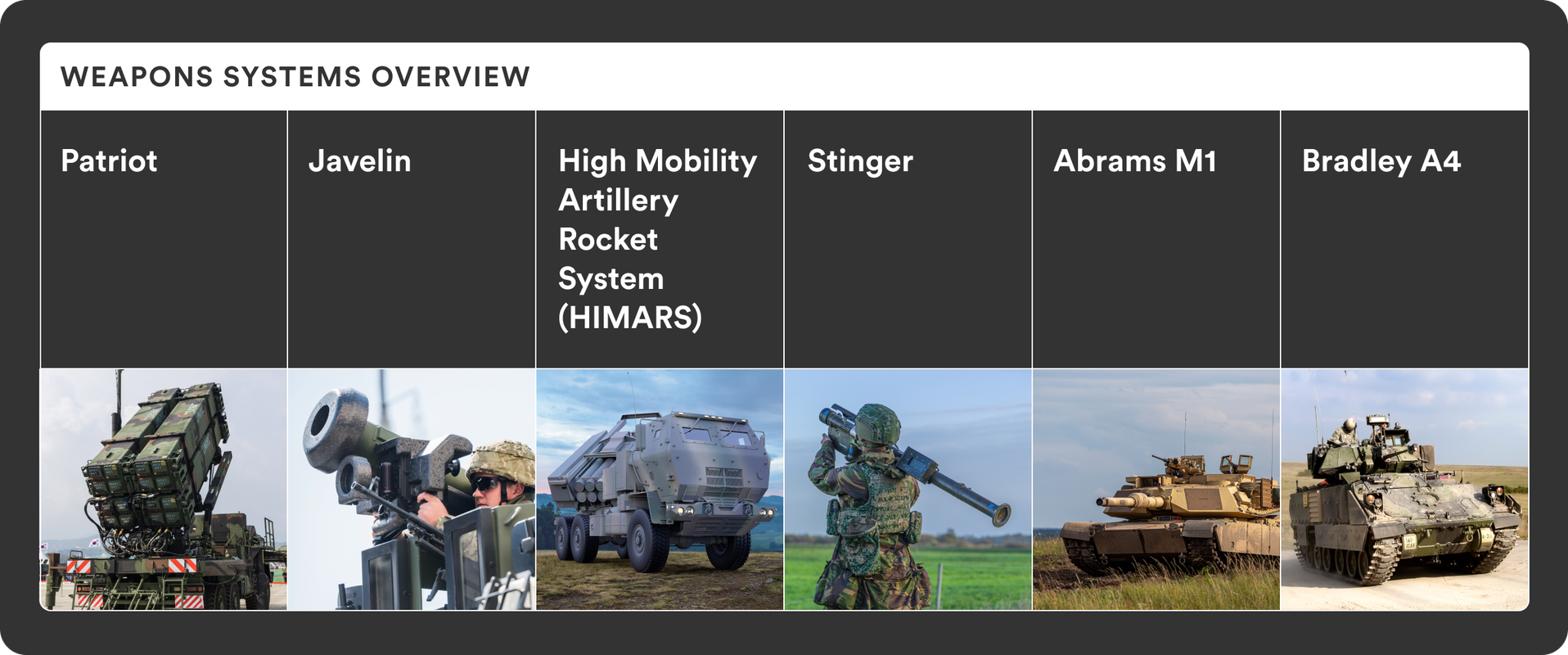

As NATO enters its most consequential phase since the Cold War, the weapons shipped to Ukraine are doing more than reshaping the battlefield. They are reordering the industrial base of the West, breathing life into places globalization forgot. The scale of this revival is striking, fueled by almost two decades’ worth of military spending compressed into three years. Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the United States has obligated more than $18.7 billion for the production of six key weapons systems—HIMARS, Patriots, Stingers, Javelins, Abrams tanks, and Bradley fighting vehicles—all critical to Ukraine’s battlefield resilience. That figure represents more than 80 percent of the sum awarded for those same systems over the previous two decades, creating a wartime industrial surge that is reviving factories and supply chains across the country.

A similar industrial rebound is unfolding across the Atlantic. In the small French town of Bourges—a key hub for missile production with a population of 64,000—production shifts have expanded and hiring has surged by about 50 percent annually, according to The Economist. MBDA, one of Europe’s leading defense manufacturers with major operations in Bourges, plans to add about 2,600 workers to its payroll. Missile production is already up by more than 30 percent over the past year, with output expected to double by the end of 2025.

The European Commission’s March 2025 announcement of an $870 billion defense spending surge delivered a much-needed jolt to the continent’s industrial base. Demand is accelerating fast: In mid-March, France, the United Kingdom, and Italy jointly placed an order for 218 anti-aircraft missiles—further evidence that Europe’s rearmament push is shifting from rhetoric to reality. Taken together, these figures underscore that Europe’s defense-industrial surge is no less real than America’s—driven not by showy White House browbeating and watered-down summit communiqués, but by expanding factory floors, extended shifts, and the urgent imperative of transatlantic industrial resilience.

Defense analysts are still parsing what NATO’s late-stage industrial awakening means in practical terms—and how far it can be measured in real procurement numbers. One widely cited estimate suggests that between June 2022 and June 2023, 78 percent of European defense procurement spending went to non-European suppliers, including 63 percent to U.S. companies. That imbalance is beginning to shift, according to a more recent 2024 study by the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Of the platform-procurement contracts signed by NATO’s European members between February 2022 and September 2024, 52 percent went to EU-based manufacturers and 34 percent to American suppliers.

Yet the realities of decades of baked-in imbalance between America’s outsized defense industrial capacity and Europe’s more fragmented, under-resourced production base are not easily erased, particularly as the war in Ukraine drags on and stockpile demands mount. In the context of that conflict and others, including the escalating clashes between Iran and Israel, it is the United States that leads the way in producing the weapons that matter most when time, precision, and deterrence are in short supply. With the Pentagon shifting its focus to China and shoring up Indo-Pacific security, NATO is in a strategic fix that is likely to persist for some years to come. For all the talk of European rearmament and strategic autonomy, the continent remains years away from fielding an industrial base capable of matching the speed, scale, or precision of American production.

“For all the talk of European rearmament and strategic autonomy, the continent remains years away from fielding an industrial base capable of matching the speed, scale, or precision of American production.”

The asymmetry is not only structural—it’s material. Camden, Arkansas, illustrates this imbalance: This single American town can rapidly scale production of critical weapons systems like HIMARS, while Europe lacks equivalent concentrated production capacity.

Even as Congress debates the future of military aid to Ukraine—and Republicans remain divided under pressure from Trump to pull back—towns like Camden have emerged as nodes in a largely hidden wartime economy. On the surface, they illustrate how NATO’s commitments can deliver real economic benefits to American communities. But beneath that, their stories expose deeper structural vulnerabilities: political volatility, overreliance on aging weapons systems, and a defense supply chain stretched thin by years of strategic drift.

As the Trump administration signals a shift in Ukraine policy—including the weeklong suspension of military aid in March 2025—another, more domestic question looms: What happens to the American factory towns revived by wartime weapons contracts if that aid dries up? Drawing on employment data from key defense hubs, this analysis reveals how Ukraine-related production has created a fragile industrial revival—one that reshaped local economies, rebuilt depleted workforces, and exposed deep new dependencies in the U.S. defense supply chain. The same systems now sustaining Ukraine’s frontline could soon be essential in the Indo-Pacific. Weakening them now risks undercutting America’s readiness for the next crisis.

Missiles, Jobs, and the New Arsenal Economy

At the heart of this emerging arsenal economy lies an existential question: Can the United States and Europe reconcile their divergent approaches to defense industrial policy in time to build a resilient, interoperable security architecture? In 2022, the United States swiftly ramped up production through wartime authorities and long-standing contracting pipelines. But Trump’s skepticism about NATO, the EU’s fragmented procurement landscape, and European anxieties over strategic autonomy have raised fresh doubts about the long-term viability of a military alliance that, until now, has held for nearly 80 years.

At a recent gathering in June of security experts at the 20th Annual GLOBSEC Forum in Prague, one question was on everyone’s lips: Can Europe pull off its defense transformation in time to meet the looming threat from Russia? NATO’s former Supreme Allied Commander Philip Breedlove estimates that President Vladimir Putin may be just two to five years away from testing NATO’s collective defense resolve. “If we really started doing a good job investing now, which arguably we haven’t done so well in the past—but if we did a really good job at investing now and we kept investing at our old rate, how do we overcome 30 years of procurement holiday?” Breedlove asked during one panel. “We’ve been trying to hug the bear for 30 years. He has no intention of being a partner. Now, after 30 years of not investing and trying to catch up on the deficit, we have to change something.”

As U.S. defense firms absorb the lion’s share of NATO-linked contracts, pressure is mounting in Brussels, Paris, and Berlin to rebalance the industrial equation. The future of the alliance may depend less on summit speeches and more on whether supply chains, labor markets, and procurement decisions on both sides of the Atlantic can converge in ways that meet the moment. The gap between transatlantic ambition and operational reality is perhaps best illustrated by the role of a single system that reshaped the battlefield—and revitalized an overlooked corner of the American South.

In June 2022, four months into Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukraine received its first shipment of highly mobile and precise HIMARS rocket launchers from the United States. Though initially limited to shorter-range munitions, the systems gave Ukrainian forces the ability to carry out pinpoint strikes on Russian supply depots, command centers, and transportation infrastructure. Their precision and mobility altered the battlefield dynamic, forcing the Russians to adapt their tactics and laying the groundwork for Ukraine’s successful counteroffensive in the southern Kherson region later that summer and fall.

As HIMARS helped shift the battlefield in Ukraine, their production was transforming the economy of a small American town thousands of miles away. In Camden, Arkansas, a town of 10,000 and home to the Lockheed Martin plant that assembles the launchers, jobs in the aerospace sector have surged since 2022, reversing pandemic-era losses and offering wages well above the regional average.

This dual effect—strategic utility abroad paired with industrial recovery at home—captures a broader trend that U.S. policymakers should consider. By tracking actual job creation rather than spending alone, we find that U.S.-built weapons systems not only proved critical to Ukraine’s defense but also reversed years of manufacturing decline in American communities. As the White House weighs its Ukraine policy, these employment gains represent tangible stakes for American workers and the defense-industrial base the administration has sought to reinforce.

“As the White House weighs its Ukraine policy, these employment gains represent tangible stakes for American workers and the defense-industrial base the administration has sought to reinforce.”

From Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 through the second quarter of 2025, Congress approved $124.8 billion in supplemental defense spending to support Kyiv’s war effort. Of that, Congress appropriated $45.8 billion toward replenishing Department of Defense weapons stockpiles, funding new production by American defense manufacturers. Think tanks like the Center for Strategic and International Studies, the American Enterprise Institute, and the Foundation for Defense of Democracies have traced the war’s economic ripple effects across the United States. Our analysis drills down on six weapons systems driving job growth—and sets the stage for a deeper look at how the Ukraine war, a second Trump term, and Europe’s push for “strategic autonomy” are reshaping the transatlantic defense economy.

A dig through publicly available data revealed a simple but often overlooked metric: jobs created, not just dollars spent. Tracking employment changes in their manufacturing communities reveals where defense spending has had the most transformative impact. According to USAspending.gov contract data through the end of 2024, these systems received nearly $18.8 billion in commitments since 2022, almost as much as the $23.2 billion obligated over the previous two decades.

Source: Flying Camera, Katatonia82, Mike Mareen, Arjan van de Logt, M2M_PL, Andrew Harker via Shutterstock

Figure 1 below illustrates the cumulative dollar value obligated by the U.S. Department of Defense for six key weapons systems supplied to Ukraine: HIMARS, Patriot systems, Javelins, Stingers, Abrams tanks, and Bradley fighting vehicles. The data shows a sharp surge in commitments between 2022 and 2024, compressing nearly two decades’ worth of spending into just three years. The steep rise reflects an unplanned industrial scale-up that is reviving U.S. defense manufacturing towns. While the largest obligations went to Patriot systems and Abrams tanks, the smallest increase—HIMARS—arguably had the most pronounced local impact, revitalizing Camden, Arkansas, where the system is produced.

Nearly 300,000 Americans work in manufacturing industries tied to missile and armored vehicle production, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics employment data. The aerospace sector, which includes many of the facilities producing these systems, offers some of the highest wages in manufacturing, with average annual earnings around $120,000. That figure stands well above the national average for manufacturing jobs, underscoring how defense spending is not only sustaining employment but elevating it.

By comparing year-over-year job growth in defense-related manufacturing against broader local employment trends, we can identify where defense contracts have served as a clear economic engine. A close look at the primary manufacturing sites for each of the six systems reveals four consistent patterns:

- Timing matters. The most significant job gains occurred six to 12 months after major contract awards. Missile production sites saw faster employment gains than heavy equipment facilities, likely due to shorter production ramp-up times.

- Geography matters. Sunbelt states, particularly those with established aerospace sectors, generally experienced stronger recoveries than their Northeastern counterparts, even when contract values were similar.

- What gets built matters. Communities producing complete systems, such as HIMARS launchers or full Patriot batteries, saw more pronounced employment growth than those focused on components or subassemblies.

- Defense helps economic recovery. Communities with substantial defense manufacturing recovered from pandemic-era job losses faster than nearby regions without major defense exposure.

HIMARS and Patriots: High-Tech Missile Manufacturing Revival

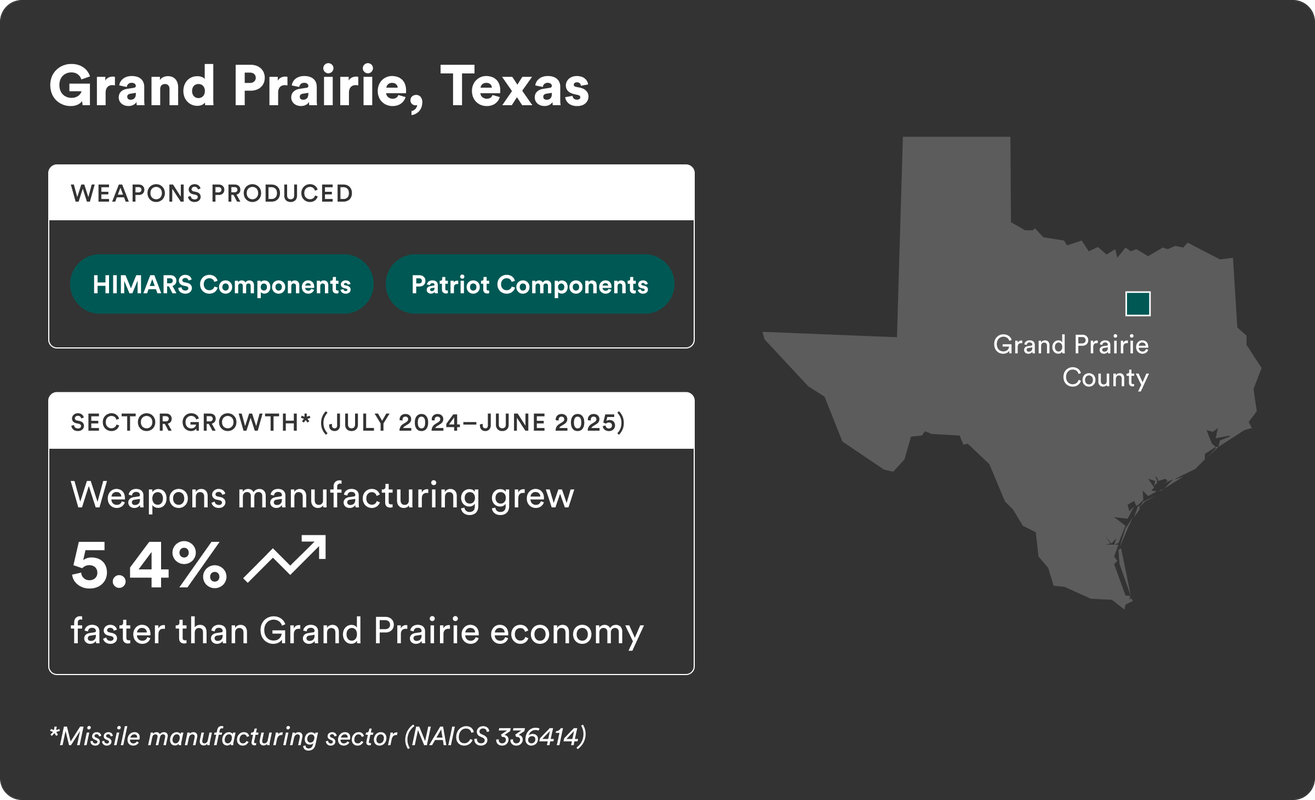

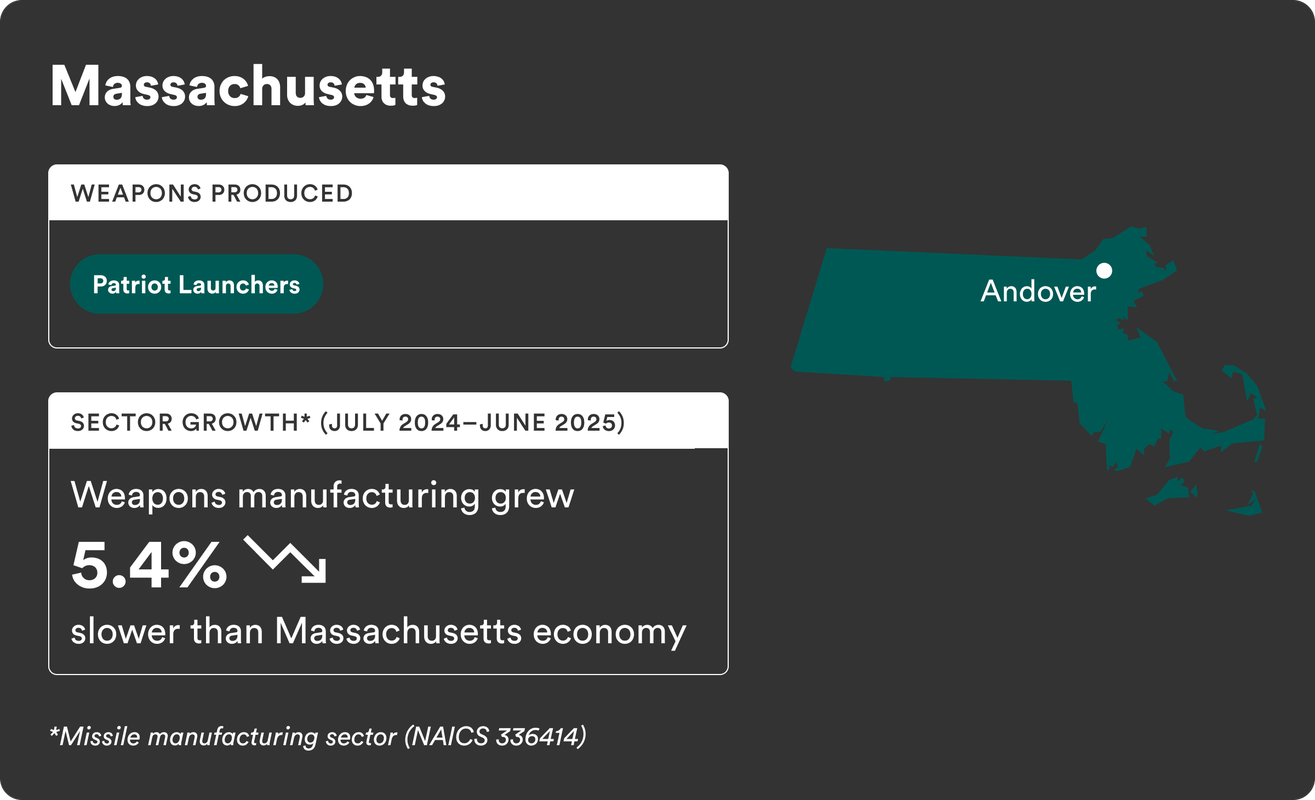

Figure 2 shows how U.S. defense obligations for HIMARS and Patriot missile systems have translated into measurable employment gains across three states—Arkansas, Texas, and Massachusetts. The chart tracks the geographic distribution of high-tech missile manufacturing linked to Ukraine-related contracts, highlighting the localized nature of the industrial revival. While Lockheed Martin’s Camden, Arkansas, facility saw a major ramp-up in HIMARS production, facilities in Grand Prairie, Texas, and Andover, Massachusetts, also experienced employment growth tied to the Patriot system. Together, these states illustrate how targeted defense investments are reshaping regional economies and deepening NATO’s industrial interdependence.

The economic revival of Camden, Arkansas, offers perhaps the most compelling example of how these strategic systems are affecting American communities. Located in southern Arkansas, an hour’s drive from the Louisiana border, Camden hosts Lockheed Martin’s production facilities for both HIMARS launchers and Patriot PAC-3 missiles, employing over 1,200 workers. Before the war in Ukraine, employment in Ouachita County, where Camden is located, had been declining, falling from over 12,500 jobs in 1990 to just 8,513 by 2021, a loss of more than 4,000 jobs over three decades. Contract awards related to Ukraine have helped reverse this trend, with employment jumping by over 800 jobs in 2022, though some of these gains have since moderated.

In October 2022, Lockheed Martin opened a new All-Up Round III (AUR III) missile production center in Camden, increasing PAC-3 production capacity and bolstering employment. The production rate for HIMARS doubled from 48 to 96 units annually, while Patriot missile production increased from 300 to 500 missiles per year. In Arkansas over the last year, from July 2024 to June 2025, weapons manufacturing grew almost 20 percent faster than the economy overall. These increases represent not just a response to immediate needs but investments in long-term production capacity.

Figures 3, 4, 5, and 6 below illustrate the gap between U.S. defense policy commitments and actual missile manufacturing output following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. While federal obligations for high-demand systems like HIMARS and Patriots surged in 2022 and 2023, production in key missile manufacturing hubs lagged behind state-level economic growth until mid-2024. This lag reveals the limitations of the Biden administration’s early approach to arming Ukraine—characterized by rapid aid authorizations that outpaced the capacity of an atrophied industrial base. The delayed uptick in manufacturing reflects a belated mobilization effort, suggesting that while political will was strong, the U.S. defense supply chain required time and investment to respond. The trend highlights a core strategic vulnerability: Even with substantial funding and bipartisan support, industrial readiness remains a limiting factor for sustaining military assistance—whether in Ukraine or future contingencies linked to Taiwan or the South China Sea in the Indo-Pacific region.

Similarly, in Grand Prairie, Texas, where additional HIMARS and Patriot components are manufactured, aerospace employment has outperformed overall job growth in the region while weapons manufacturing grew faster than the overall economy. The sector now employs over 2,800 workers at significantly higher wages than the regional median. Our analysis of Bureau of Labor employment data shows that while contract awards came shortly after the invasion began in early 2022, the most significant employment gains appeared six to nine months later, demonstrating the lag between funding and workforce expansion.

Interestingly, Patriot launcher production in Andover, Massachusetts, hasn’t shown the same employment boost as missile production sites in Arkansas and Texas. Despite substantial orders, aerospace employment in Massachusetts has largely tracked with overall job trends.

One possible explanation lies in industrial diversity: Massachusetts has built its economy around biotech and health care since federal research funding transformed the state in the 1960s, making defense contracts a smaller piece of a larger economic picture. In 2023, the median household income in Andover was $127,054, compared to $78,889 in Grand Prairie, Texas, and just $51,300 in Camden, Arkansas. These income disparities reflect decades of divergent development paths, with places like Camden lacking the university infrastructure and federal research investments that diversified other regional economies. Where defense contracts represent a larger share of local economic activity, their employment effects become more visible and transformative.

Anti-Tank Warriors: The Javelin and Stinger Renaissance

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion in February 2022, the U.S. defense industrial base confronted a sobering reality: Not a single new Stinger anti-aircraft missile had been produced since 2005. This wasn’t simple neglect. Two decades of counterinsurgency warfare had reshaped American military priorities. Building a nimble, rapidly deployable, air-dominated military diverted funding from industrial-scale production more suited to fighting another conventional force. The result was the atrophy of capabilities essential for high-volume conventional warfare. With Ukraine urgently requesting shoulder-fired systems to defend against Russian aircraft, Raytheon was forced to restart a long-dormant production line in Tucson, Arizona, even recalling retirees to help revive operations.

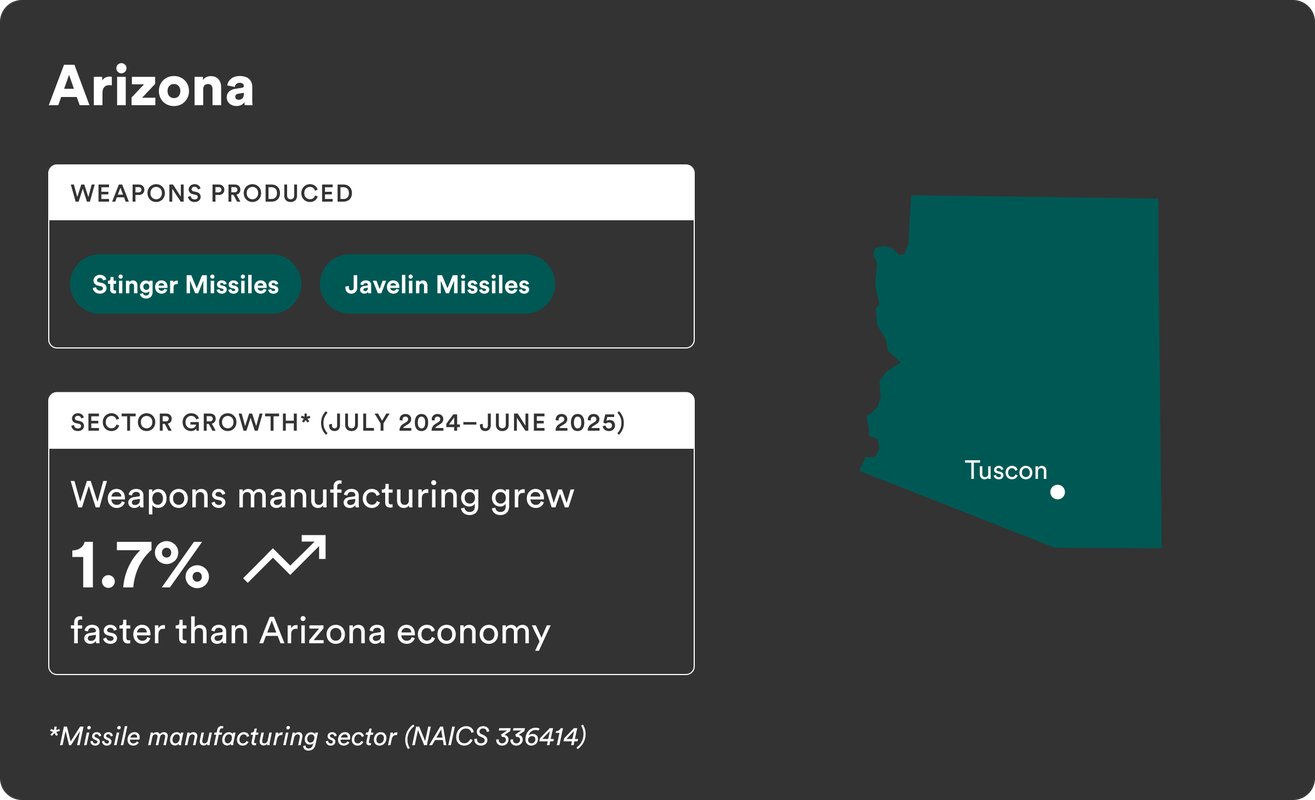

Arizona already had high employment exposure in the aerospace sector, but our analysis shows that Raytheon’s substantial contracts for Stinger missiles gave the local economy a distinct post-pandemic lift, and weapons manufacturing grew slightly faster than the general economy. The U.S. Army awarded a $625 million contract in May 2022 for up to 1,468 Stingers—the first such award for new Stinger missiles in nearly two decades. Employment in Arizona’s guided missile and space vehicle manufacturing sector began growing at a faster rate than overall state employment after the Department of Defense awarded Raytheon these contracts.

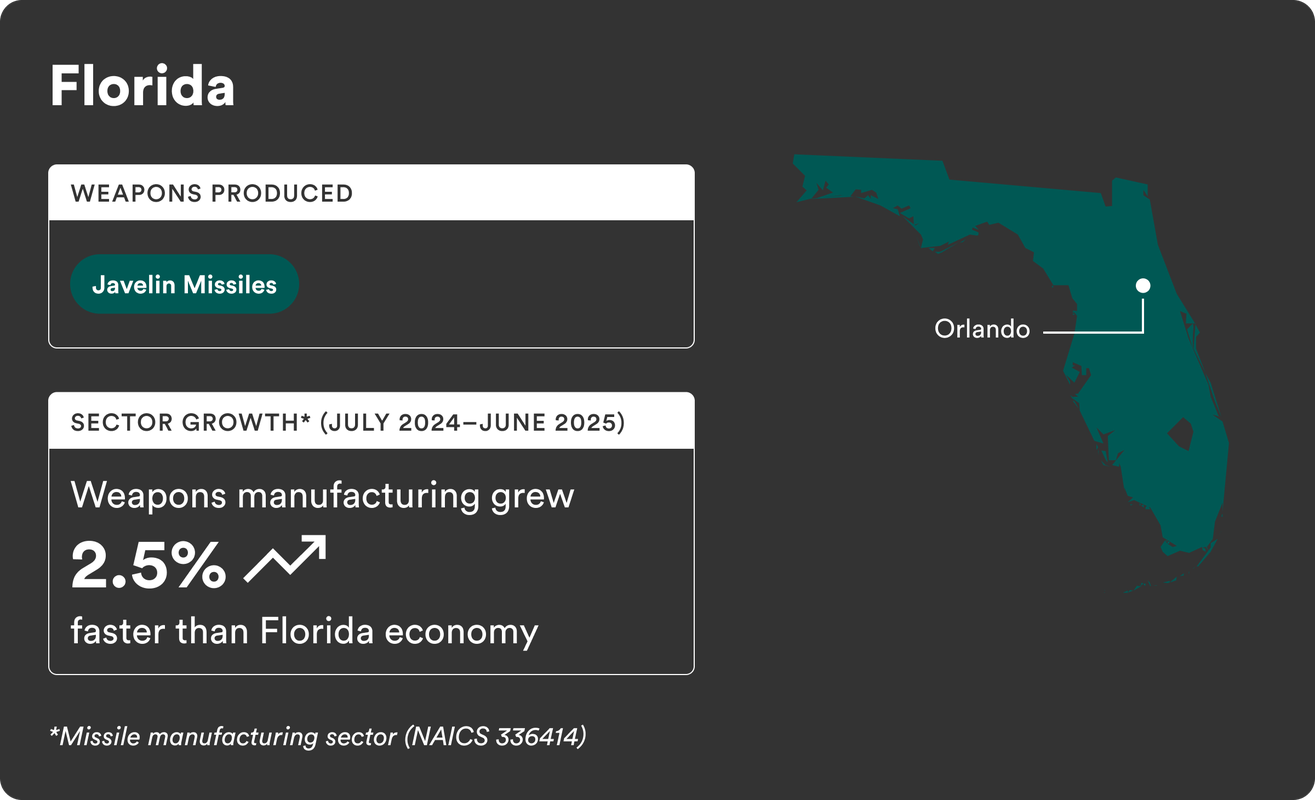

The Javelin anti-tank missile, produced through a joint venture between Lockheed Martin and Raytheon, tells a more complicated story. With production split between Orlando, Florida, and Tucson, Arizona, the economic impact has been harder to isolate. Florida’s aerospace employment growth predated the Ukraine contracts, suggesting broader industry trends at work. One reason for this may be the outsized role that Florida plays in the commercial aviation and space technology sector. But as shown below, growth in weapons manufacturing outpaced the state’s economy. The production surge speaks for itself: Output reached 2,400 per year in 2024 and will climb to 3,960 by late 2026. The Army’s May 2023 award of a three-year, $7.2 billion contract for Javelin production reinforces an already-growing aerospace sector.

America’s Armored Backbone: Tanks and Fighting Vehicles

The Army Tank Plant in Lima, Ohio, America’s only facility for producing M1 Abrams tanks, has undergone a striking revival. Once down to producing just 12 Abrams tanks per year, the plant is now scaling up to meet orders, replacing armor sent to Ukraine and NATO allies. Poland alone has ordered 366 Abrams tanks through two separate deals, making it the first U.S. ally in Europe to receive these systems, apart from Ukraine. These orders will keep the Lima plant’s 360 highly specialized workers employed for years to come.

As of early 2025, transportation equipment manufacturing in Allen County, where Lima is located, is growing faster than the region’s overall job market, a sharp reversal from the post-pandemic slump. Unlike missile systems, however, tank production shows a longer lag between contract awards and workforce expansion, likely reflecting the complexities of ramping up heavy equipment manufacturing.

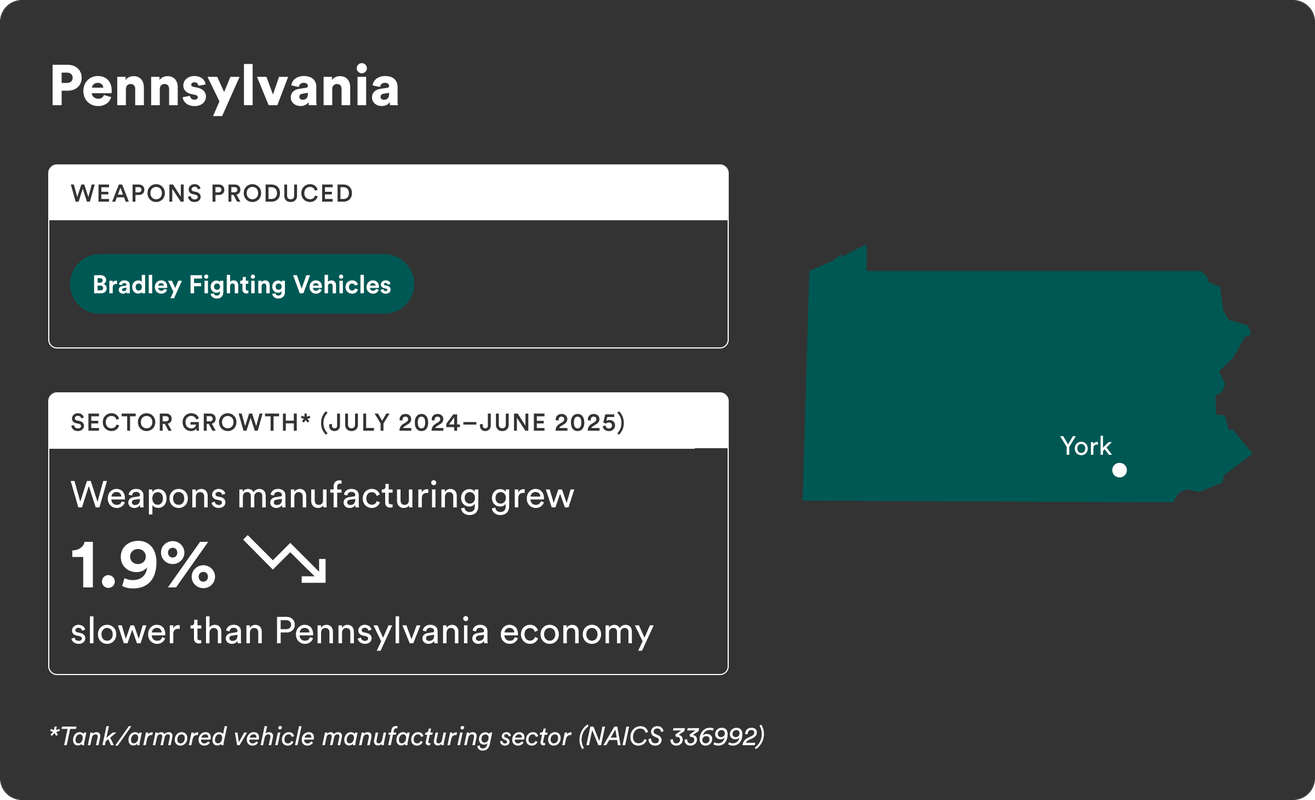

The Bradley Fighting Vehicle has brought similar gains to York, Pennsylvania, where the British defense giant BAE Systems runs its primary production line. What sets the Bradley apart, economically, is the breadth of its supply chain. Supporting components are cast and assembled in foundries and factories scattered across South Carolina, Alabama, Minnesota, California, and Michigan, spreading the industrial benefits across a wide swath of the country.

Congressional Action and the Future of Defense Manufacturing

The revival of America’s defense manufacturing towns hasn’t happened in a policy vacuum. Congress has taken steps to strengthen the industrial base, recognizing its dual role as a strategic asset and an economic anchor. A growing bipartisan consensus has emerged: Ensuring readiness against future threats requires not just funding, but greater stability in how that funding is delivered.

One sign of this shift is Congress’s expansion of multiyear procurement authorities to include high-demand munitions. In 2024, legislators authorized the Army to award multiyear contracts for HIMARS’s Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System (GMLRS) munitions, Patriot PAC-3 interceptors, Javelin missiles, and other key systems. As the congressional explanatory statement noted, this authority aims to “stabilize the defense supply base with predictable production opportunities,” a recognition that the boom–bust cycle of defense procurement had partially hollowed out America’s arsenal.

Yet even as Congress moves to stabilize production through long-term funding commitments, its traditional oversight mechanisms can create unintended consequences for the defense industrial base. A March 2025 report from the Congressional Research Service noted that Congress has “never successfully blocked a proposed arms sale via a joint resolution of disapproval” but has “affected the timing and the composition of some arms sales” by voicing opposition during the preliminary notification process.

These oversight tools remain an essential check on executive authority, and rightly so. But their exercise requires careful consideration of downstream effects. When Congress delays or modifies a major arms sale, it doesn’t just postpone a delivery date. It can potentially force manufacturers to halt production lines, lay off specialized workers, and defer orders from suppliers. These disruptions may prove challenging to absorb for an industrial base that has already been weakened by decades of inconsistent demand. Congressional oversight must weigh not just the immediate policy merits of an arms transfer, but also whether a hold today might mean an inability to produce critical systems tomorrow.

Use It or Lose It: Retaining Specialized Skills and Technical Know-How

The human dimension of this industrial mobilization deserves special attention. When Raytheon recalled retirees to restart Stinger production, it highlighted a vulnerability in America’s defense workforce. The specialized knowledge required to manufacture these systems, from the precision engineering of Patriot radar seekers to the metallurgy of Abrams armor, cannot be quickly or cheaply replaced. Congressional efforts to sustain production serve not just to maintain assembly lines but to preserve hard-to-replace human capital and institutional knowledge.

Over the long term, the National Defense Strategy Commission has warned that declining and inconsistent defense budgets have eroded the industrial base. From 2011 to 2022, defense spending dropped from 4.4 percent of GDP to just 2.9 percent, approaching post–World War II lows. That decline has weakened the link between strategy and capacity. The commission has called for annual real growth of 3 to 5 percent in defense spending, not only to meet operational demands but also to sustain the communities that keep production running. Towns such as Camden, Arkansas, and Lima, Ohio, rely on predictable investment. In turn, they supply the workforce and infrastructure essential to American defense.

Closing the Distance Between The Hague and Camden

Our analysis began with the distance between The Hague and Camden—not just in miles, but in mindset. What we have found is that the United States and Europe have a long road to travel before either reaches the long-stated goals of unity, balanced burden-sharing, and credible deterrence to potential rivals. The gap between what is needed now to stave off Russian advances in Ukraine and what might be needed in the event of an Article 5 contingency when it comes to China also has implications for U.S. military readiness. While NATO leaders debate the alliance’s future in airless summit halls, the real engine of transatlantic security is humming in factory towns and missile plants thousands of miles away. Yet, the numbers underscore the risks posed by Washington’s herky-jerk politics over America’s NATO commitments.

Production for Ukraine has done more than blunt Russia’s advance. It has created a mutually reinforcing cycle between strategic capability and economic vitality—reviving dormant supply chains, retraining idle hands, and rebuilding the industrial capacity essential for deterrence. From Arkansas to Arizona, defense contracts have reversed decades of manufacturing decline in communities that globalization left behind. Trump may want and might even win the argument over NATO’s reorientation, but the data indicates that American and European defense interdependence will likely be an enduring feature of the next decade or more.

But there is no question that the alliance is fragile. Political fractures, procurement delays, and shifting battlefield needs threaten to stall the alliance’s industrial resurgence. Policy decisions about Ukraine support must therefore account for both the immediate demands of war and the long-term health of the arsenal economy on which future security depends.

The Trump administration’s temporary suspension of military aid to Ukraine in March 2025 exposed the vulnerability of defense-dependent manufacturing communities. While transfers resumed after a week, the episode demonstrated how quickly procurement policies—on which these communities now rely—can change.

The consequences of a sustained pullback would vary by sector and by geography. Missile production facilities in Camden, Arkansas, and Tucson, Arizona, face the most immediate risk. Without steady orders, their backlogs will run dry within months, triggering layoffs. Heavy equipment manufacturers have a bit more cushion. Foreign military sales—like Poland’s order for 366 Abrams tanks—should sustain operations in Lima, Ohio, through 2026, regardless of Ukraine policy.

But the risk runs deeper than job loss. Rebuilding dormant production lines, like those used for Stinger missiles, required extraordinary effort—recalling retired engineers, resurrecting defunct supplier networks, and restoring long-lost technical know-how. The expanded capacity for HIMARS, Patriots, and Javelins represents years of investment in tooling and training. Once lost, that capacity is expensive and slow to recover.

This analysis reveals a deeper reality: Ukraine-bound weapons have catalyzed an arsenal economy that ties strategic capability abroad to economic renewal at home. Yet the durability of that cycle hinges on choices still to come. What we’ve captured here is just the beginning. Closing the distance between summit declarations and shop-floor realities will require sustained attention, sharper data, and more targeted analysis. We intend to keep tracking that arc—between Camden and The Hague, between contract and consequence.

The implications go far beyond Europe. As Washington increasingly turns its gaze toward the Indo-Pacific and the challenge posed by China, the need for resilient, scalable defense production becomes even more urgent. The same factory floors supplying Ukraine today could be decisive in a future conflict over Taiwan or in bolstering deterrence across the Pacific. What’s at stake is not only the future of NATO, but the credibility of American power in a multipolar world.