Sallie Mae's Blame Game

Blog Post

Jan. 8, 2008

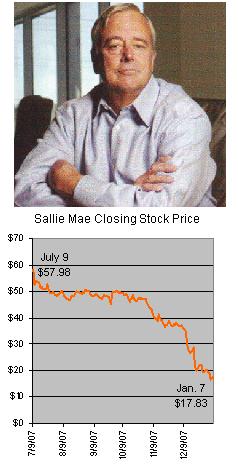

When student loan giant Sallie Mae announced on Monday that it was removing Al Lord, the company's Chief Executive Officer (CEO), from his position as Executive Chairman of the board a little more than a month after he took the job, it went to great lengths to portray the move as business as usual. But investors, financial analysts, and the news media weren't buying it. The fact Sallie Mae had handed control of its board to an individual who has been touted as "a turnaround specialist" speaks volumes about the degree of panic that has overtaken the company's headquarters in Reston.

Predictably, Sallie Mae is putting a large measure of the blame for its freefall on legislation Congress approved in September that cut excess lender subsidies to pay for a significant increase in the maximum Pell Grant for low-income students. Never mind that in its legal fight against J.C. Flowers & Co., the private equity firm that backed out of purchasing the company this fall, Sallie Mae has stated that the cuts were only incrementally worse than they had been expecting for months. The company is also blaming its woes -- perhaps with greater justification -- on a tightening of credit markets.

But in playing the blame game, Sallie Mae should take a long, hard look in the mirror, as a good part of its misfortune is the result of its irresponsible and arrogant leaders.

Ever since Al Lord wrested control of the company by leading a shareholder revolt against its former management in 1997, he has run Sallie Mae with a degree of hubris and belligerence that would make former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfield proud. That fact became painfully clear to investors and financial analysts last month when Lord's disastrous performance during a conference call on the company's earnings sent the company's stock plunging. That call, which ended with Lord berating an analyst and cursing, was eerily reminiscent of one Enron's Jeff Skilling gave only months before that corporation collapsed.

While that conference call is the most obvious example of how the top leaders' arrogance has harmed the company, here are a few others that help explain the dire straits in which Sallie Mae finds itself:

The Collapse of the Buyout Deal

Sure, Lord et. al had every right to be upset when J.C. Flowers & Co. got cold feet on its initial offer to purchase Sallie Mae for $25.3 billion or $60 a share. That would have been quite a deal for Sallie Mae's leaders and investors, as the offer represented almost a 50% premium over its stock price before news of a potential takeover became public. Lord himself was set to make out like a bandit. Had the takeover gone through, he was expected to rake in nearly $225 million from cashing in his stock options.

But while Flowers did pull out of the original deal, he did try to renegotiate. And the terms he offered -- $21 billion, or $50 per share -- look like they would have been a steal for Sallie Mae, given the price at which the stocks are trading now. But in typical fashion, Lord refused to budge and instead decided to take the equity firm to court to demand the $900 million "break up fee." He also took potshots at Flowers in the news media and during an investor conference call that appeared to be aimed at shaming him into following through with the initial deal.

But Flowers got the last laugh. In December, with it stock tanking, officials with the loan company had a change of heart and approached the equity firm saying they were willing to renegotiate after all. This time, Flowers turned them down.

A Bad Wager

In a fitting example of the company's hubris, Sallie Mae has entered into deals with Wall Street bankers in which it has essentially wagered that its stock price would not drop. These deals, known as equity forward contracts, are a cheap but extremely risky way for corporations to raise money by selling their stock to banks and agreeing to buy it back on a date certain at a higher price.

Perhaps the move didn't seem that risky to a company that has been nurtured and protected from birth by the federal government. After all more than 80 percent of the loans that Sallie Mae makes are fully backed by the federal government.

But with the company's stock price plunging, the company has been forced to pay for its misplaced optimism. To raise the $2 billion it needed to cover the costs of the agreements, Sallie Mae recently sold more than 100 million shares of stock. By doing so, the company further diluted shareholder value.

Subprime Lending

Over the last decade, as Sallie Mae has made a huge push to become the predominant player in the private loan market, financial analysts have repeatedly warned the company to be careful about making loans to subprime borrowers. They worried that the company, which is used to having government backing on its loans, would not properly assess the risks in lending "unsecured [private] loans to people without jobs," as Bethany McLean of Fortune Magazine put it in a 2005 article about analysts' concerns.

But Sallie Mae's leaders did not heed these warnings. Instead, they pioneered the "opportunity pool," an arrangement that allows lenders to leverage private loans to get a larger share of a college's federal student loan business. Under these types of deals, a lender gives a college a fixed amount of private loan money that the institution can provide to students who otherwise would not qualify for the loans. In return, the insitution agrees to make the loan provider "a preferred lender," or even an exclusive lender of federal loans on its campus.

Some loan industry officials acknowledge that these deals are "loss leaders," meaning that the companies are willing to risk having a certain number of private loans go into default in order to expand their presence on a campus. This especially appears to be the case with deals Sallie Mae has forged with some of the largest for profit higher education companies in the country, like Career Education Corporation and the University of Phoenix, which have been widely accused of engaging in aggressive and misleading recruiting and admissions tactics. According to a recent Senate report on improper marketing practices by lenders participating in the Federal Family Education Loan (FFEL) program, Sallie Mae calculated that Opportunity Loans it offered to one such college had an expected default rate of 70 percent.

Conclusion

Sallie Mae is paying the price for its harmful policies. Facing growing loan defaults, the company alarmed its investors last week when it announced that it is planning in the coming year to become "more selective" in making both federal and private student loans. News that the company was cutting into its core business sent the company's stock down 13 percent in one day.

So Sallie Mae can continue to lay the blame for its problems on everybody else. But if it wants to solve them, it must first heal itself.