Exploring Privacy-Preserving Age Verification: A Close Look at Zero-Knowledge Proofs

Brief

Olemedia via Getty Images

July 17, 2025

Overview

Growing societal and parental concerns about the negative impacts of digital spaces are driving a new wave of youth online safety initiatives. Increased screen time has parents, teachers, and public health officials worried about the potential harm to young people’s mental health outcomes, social connections, and development. While it is unclear exactly how and to what extent online spaces lead to negative outcomes, whistleblower reports show some companies knowingly create adverse environments for young users. In response, policymakers are seeking to hold companies accountable, improve youth experiences online, and crack down on age-inappropriate content. Much of this legislation calls for stricter age verification practices that require identification sharing requirements, which can endanger user privacy and security.

In response to the challenges raised by age verification mandates and the Supreme Court’s recent decision to allow age verification for online adult content, this brief explores a path toward implementation that protects a person’s privacy and data security through zero-knowledge proofs. To help assure that this emerging solution advances in ways consistent with a largely open and secure internet, the brief provides four key considerations that industry players and policymakers should consider to build the necessary supporting digital ecosystem. The brief also offers recommendations for policymakers and industry players that are or will be tasked with implementing age verification. These recommendations can help ensure online age verification is applied in a narrowly tailored, least restrictive manner, while also prioritizing user privacy and security.

Four Considerations for Building a Digital Ecosystem That Supports Privacy-Preserving Age Verification

- Delineate the appropriate instances for strict age verification.

- Determine the roles of different entities in the age verification process and how these entities establish trust.

- Coordinate industry action through shared standards and protocols.

- Protect user privacy, security, and rights throughout implementations.

Four Recommendations for Industry and Policymakers

- As a matter of policy, age verification requirements should be narrowly tailored to limit burdens on freedom of expression and access to protected content.

- Wherever applied, technical solutions for age verification should use best-in-class privacy-preserving techniques.

- When absolutely required, age verification mandates should be applied in the least restrictive and most tailored manner—at the service level.

- Age verification solutions and implementations should prioritize user choice and data security.

The Wave of Age Verification Mandates Poses Risks to Users

Today in the United States, almost every state has an age verification law or pending bill in its legislature. Most of these aim to prevent minors from accessing adult content, but others broadly target social media or app-store use. Even legislation that does not outright mandate age verification may implicitly require it. For example, age-appropriate design codes require companies to tailor a user’s experience or content to their age range, which necessitates first determining a user’s age. To comply with these bills, companies will need to impose some level of age verification.

While age verification seems like a simple solution, trying to determine who is and is not a child online can pose both technical and political challenges, endangering user rights, privacy, and security.

Currently, many companies use various age assurance practices to determine how old a user is. These methods range from users self-declaring their age to submitting credit card information and from facial age estimation to AI analysis of user behavior. Each method comes with its own level of accuracy, reliability, and certainty.

Often, these methods require a tradeoff between reliable accuracy and privacy. For example, strict age verification can provide increased accuracy by requiring users to submit hard identifiers, such as a government-issued ID or biometric data. Access to such sensitive and identifying personal information can compromise an individual’s ability to remain anonymous online. At the same time, sharing personal information with online providers who must then process, confirm, and potentially store this data creates unnecessary risks of data exposure, surveillance, and breach. Age verification also raises free expression concerns. Mandates can prevent any eligible user who does not have accepted ID from accessing content they have a right to, and can create further complications for young people, and their parents, who may not be able to obtain formal forms of ID.

As it stands, no currently implemented age assurance solution can provide the necessary balance between reliable accuracy and user privacy. A 2022 analysis by the French Commission on Information Technology and Liberties (CNIL) investigated six common solutions for online age assurance. CNIL found that none could adequately satisfy “sufficiently reliable verification, complete coverage of the population, and respect for the protection of individuals’ data and privacy and their security.”

SCOTUS Reverses Course on Age Verification—but Only for Adult Content

Age verification mandates’ potential to infringe on individuals’ privacy and free expression has fueled criticism and litigation in the United States. Previously, the U.S. Supreme Court found online age verification laws to infringe upon First Amendment rights. In the recent Free Speech Coalition v. Paxton case, however, the court departed from precedent with a six-three decision to uphold Texas H.B. 1181, which mandates age verification for access to sexual content online.

The ruling found that the burden on adults’ speech is only “incidental,” and therefore the law is subject to intermediate—rather than strict—scrutiny. Under the standard for intermediate scrutiny, laws that burden speech must advance an important governmental objective. While the means of enforcing those laws must be substantially related to that government interest, states do not need to implement the least restrictive or most effective means of achieving that interest. This means that in an effort to protect youth from obscene content, states like Texas do not need to consider whether the law impacts adults in addition to minors nor whether age verification is the most effective method of preventing minors from accessing adult content.

The court’s assessment that age verification’s burden to adults is incidental does not fully account for the data privacy and security risks that the Open Technology Institute and other civil society advocates have long underscored. In physical brick-and-mortar stores, people can simply flash their ID in person to complete age-restricted purchases and place that ID back in their pocket. But the online context is different. Current online age verification methods require users to upload copies of their ID and/or submit a photo of themselves to be verified. Once this information is shared, users cannot unshare it. This process opens up people’s personal, identifiable information and online activity to risks, including retention, sale, theft, exposure, and surveillance. This burden is not merely incidental. Instead, age verification requirements can chill the online activity of users who are unwilling to take on these risks to their data.

The court narrowly tailors its ruling to the use of age verification to prevent minors from accessing sexually explicit content, and states should interpret it in this way. But, concerningly, the opinion also notes that “adults have no First Amendment right to avoid age verification.” That language creates confusion, as it seems to suggest that the court is not discouraging age verification in contexts broader than age-gating sexually explicit content. Some states are likely to test the boundaries where age verification is permissible, as already seen with states advocating for social media and app store age verification. While lower courts have blocked some of these laws, it is unclear how the new Supreme Court decision will impact final rulings or potential appeals.

Even if this reversal of precedent is narrowly understood, it will likely encourage states to move forward with implementing online age verification for sexually explicit content and perhaps other categories of speech they define as obscene for minors. To safeguard Americans against data privacy and security risks, a range of technical, policy, and industry stakeholders must work together to ensure age verification techniques that preserve privacy are properly implemented and then widely adopted.

How Can Privacy-Preserving Age Verification Work?

Strict age verification, as it is commonly practiced today by requiring hard identifiers, amounts to the verification of one’s identity—but it does not need to be that way. Age verification can be done without requiring a user to share any other information about themselves outside of their age.

While the 2022 CNIL study found that current age assurance methods failed to adequately meet reliability, privacy, and security requirements, it demonstrated a proof-of-concept that could meet them. This proof-of-concept relied on two cryptographic techniques to protect user anonymity: group signatures and zero-knowledge proofs. The group signature allows a user to authenticate data without disclosing their identity, and zero-knowledge proofs (ZKPs) provide a method for verifying a user’s shared data without disclosing any information beyond whether or not the data is valid. By combining these two concepts with third-party facilitators, the researchers created a double blind system where only a user’s age is shared.

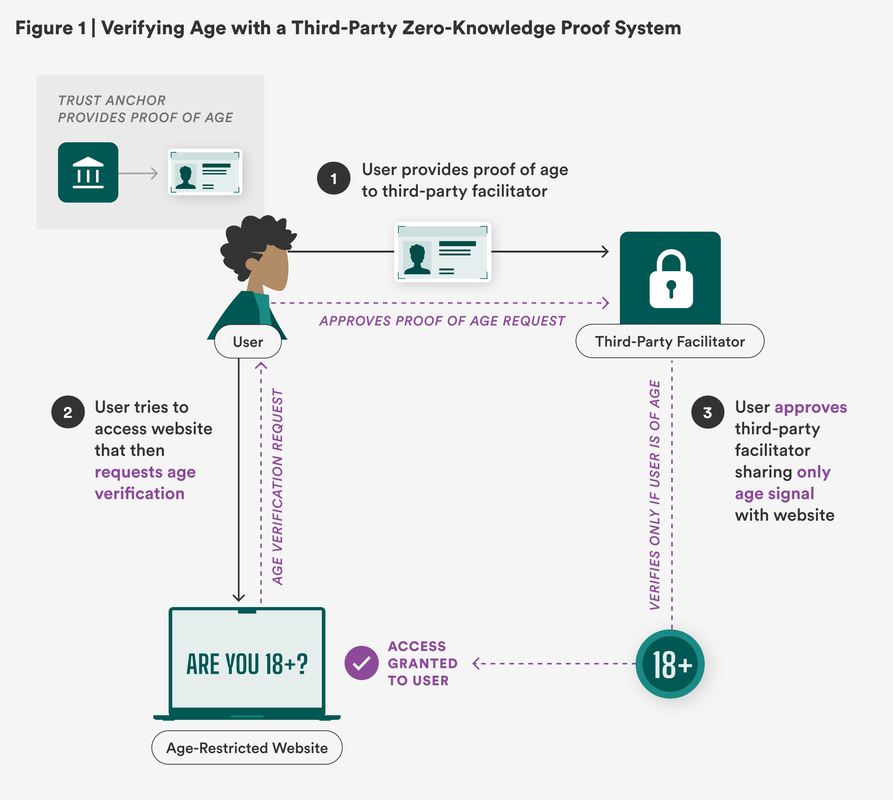

In this third-party ZKP system, an established trust anchor (also called an issuer or credential provider)—such as the government agency responsible for issuing an ID—provides a person with a digital proof of age (or in some cases identity). Users can then use a trusted third-party facilitator (sometimes called a prover or holder), such as a digital wallet or an app dedicated to age verification services, to help them store, share, and manage their proof of age. This can be done, for example, through the use of a digital token. When age verification is requested by a website or online operator (also called a verifier), the third-party facilitator can help the user share the appropriate age signal (often simply with a yes/no answer) without sharing any other information about the user. At the same time, the third-party facilitator receives only the age verification request without learning any information about the website being accessed. In this way, both parties are “blind” to all user data except age.

While the digital ecosystem needed to support this process does not fully exist yet, privacy-preserving age verification could work like this:

Source: Alex Briñas/New America

Step 1: Individuals demonstrate proof-of-age, provided by an established trust anchor, to a third-party facilitator to help them manage online age verification checks. (As illustrated in Figure 1, a person uploads a copy of their driver’s license to their digital wallet, which issues them an 18+ digital token.)

Step 2: When a user tries to access an age-restricted website, they are prompted with a verification check of the user’s age or age range. The user can share this request with the third-party facilitator to complete it without sharing which website is requesting this information. (As illustrated in Figure 1, a person attempts to access an age-restricted website, which prompts them to provide proof of age. Their digital wallet receives only the request to share their 18+ token.)

Step 3: The user requests the third-party facilitator complete the age verification request by providing the appropriate age signal, without sharing any other information about the user. (As illustrated in Figure 1, a person approves their digital wallet sharing their age token, which only states they are 18+, granting access to the age-restricted website.)

Interest in Zero-Knowledge Proofs Is Growing

The privacy-preserving promise of this “double blind” method has inspired various countries to further explore and develop ZKP-based age verification solutions. In the European Union (EU), a ZKP age verification protocol is being developed as part of a European-wide EU Digital Identity (EUID) framework. However, some organizations have pushed back against linking age verification tools to digital identity solutions, citing concerns over potential misuse and user privacy. While the EUID solution is set to be released by the end of 2026, the EU launched an interim age verification app in the meantime.

Countries in Europe are also individually moving ahead with privacy-forward age verification solutions. Under France’s SREN law, adult content websites were required to implement age verification, with at least one double-blind option (following standards outlined by its regulation authority) by April 2025. Aylo, the parent company of Pornhub, ended service in the country in protest against the law over data privacy and security concerns in early June. Since then, the law has been suspended while courts weigh whether it is compatible with EU law. Italy similarly released draft technical standards for age verification requiring double-blind solutions. Further technical and process methods for web providers implementing age verification were approved in May by Italy’s Communication Authority, AGCOM, and are set to go into full effect within six months. In addition, the nonprofit euCONSENT project launched a proof-of-concept for its AgeAware App in April 2025. The app issues reusable tokens based on zero-knowledge proofs to facilitate age verification.

Meanwhile, the Australian government is conducting an age assurance technology trial to examine different technical solutions, including ZKP methods. This trial will inform measures to enforce restrictions on adult content online and Australia’s newly enacted social media ban for users under 16.

Companies are also preparing for greater age verification requirements. In February 2025, Apple announced an update to its age-ratings policies and related age assurance measures. As part of this update, Apple will allow parents to share their child’s age range with app developers to inform age-based restrictions or features. In March 2025, Google released a similar legislative framework supporting the use of zero-knowledge proof age signals (proof of a user’s age or age range) with parental consent. Google allows parents to share ZKP age signals with developers and their apps that prohibit underage use or tailor content and experiences to user ages. So far, both companies have rolled out software aligned with World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) standards to enable ZKP-verified credential sharing for age verification in their digital wallets. While the use of such standards can pave the way toward interoperability, more oversight is needed to safeguard against misuse or overuse of ZKP tools.

Privacy-Preserving Methods Have Promise, but Developing Them Should Not Pave the Way for Broad Age Verification Mandates

ZKPs can make data sharing safer, and they should be a prerequisite for strict age verification that requires hard identifiers. However, age verification places burdens on user access and freedom of expression—and its use across the web should be limited.

While privacy-preserving age verification can be done, it should not be overused as part of a misguided effort to enable widespread age checks online. The momentum behind age verification for broader internet activity beyond preventing minors from accessing sexually explicit content or enforcing age-restricted purchases—such as bills aimed at social media and app stores—poses great risks to free, open, and anonymous web use. These mandates create unnecessary (and likely unconstitutional, as some lower courts have found) barriers to protected speech. In addition, subjecting people to unwarranted age verification can create a chilling effect on online activity, while also imposing greater personal data-sharing requirements on everyone.

Even with ZKP solutions, users must still obtain and submit proof of age from an established trust anchor and share it with a third-party facilitator. Traditional methods of proving one’s age online often have other identity information attached to it. For example, much age verification legislation in the United States requires this proof of age to be from a government-issued ID, a digital ID, transactional data, or any commercially viable age verification solution. As such, challenges related to people’s access to accepted forms of IDs and security of this data held by third-party facilitators still remain.

Four Considerations to Build the Necessary Digital Ecosystem to Enable Privacy-Preserving Age Verification

ZKP-based age verification methods promise to deliver improved security and privacy to users, but more work is needed to ensure protections are maintained during implementations. How age verification requirements and ZKP-based methods are implemented will determine how they impact users. ZKPs are a promising, but emerging and evolving technology. Currently, all ZKP-based age verification solutions are in a proof-of-concept or beta version. There is no fully developed, commercially available technology that can deliver such age verification at scale—though that may soon change.

A full rollout of privacy-preserving age verification requires more than just the solution itself. It also requires building the necessary supporting digital ecosystem and creating governance mechanisms that ensure data privacy and safety at every step of the age verification process. To advance such an ecosystem, industry players and policymakers must determine and coordinate (1) what entities can and cannot request age verification, (2) the roles different entities play in the age verification process and how they establish trust, (3) the use of shared standards and protocols, and (4) built-in protections for users.

- Delineate the appropriate instances for strict age verification: Just because privacy-preserving age verification is possible does not mean that any and every online action should be subject to it. Clear limits must be established for when strict age verification—completed through hard identifiers—is acceptable and when it is not. Allowing websites to trivially request age verification or requiring it for a wide range of online activity creates unnecessary barriers to participation in online life. Policymakers will need to determine which methods of age assurance are appropriate when some form of age-gating may be necessary but strict age verification is not required. For example, the U.K.’s Ofcom guidance outlines methods of “highly effective age assurance” that it deems acceptable for meeting its regulatory requirements. In this guidance, strict age verification is one among other accepted methods, including using open banking accounts and mobile network operators to verify age. In the interim, industry can also play a role in setting guidelines for when strict age verification is used. While Google and Apple are introducing technology that can facilitate ZKP age verification, these companies should critically assess which apps and developers it allows to use this software, so as not to encourage unnecessary, widespread adoption.

- Determine the roles of different entities in the age verification process and how these entities establish trust: Age verification, regardless of how it is implemented, requires some level of confirming with reliable accuracy a person’s age—as well as trust that the verifying entity has done so to a sufficient degree. For example, in the ZKP third-party system, does a trust anchor’s issuance of proof-of-age or identity sufficiently mean age has been verified? Should third-party facilitators validate the proof-of-age they receive from a user with the issuing trust anchor? At the same time, it’s important to assess and establish which entities can serve as trust anchors and third party facilitators, as well as the governance mechanisms and requirements for each. For example, can banks, telecom providers, or utility companies serve as a trust anchor, and if so, who decides and through what criteria? In addition, if methods of proving age outside of hard identifiers are deemed acceptable, then agreement is needed on which methods satisfy accuracy and reliability requirements to ensure that all third-party facilitators are operating with the same base level of established trust. Ideally, a robust age verification ecosystem would allow for some flexibility in which entities can serve as trust anchors in order to improve user accessibility and choice over how their age is verified and by whom. Accepted methods of providing proof-of-age should take into account limitations that exist. Not everyone has access to a government-issued ID or a credit card. Others may have such ID but not wish to use it for online age verification purposes. Creating a system with multiple options for accepted trust anchors gives users greater choice and lowers the barrier for participation.

- Coordinate industry action through shared standards and protocols: Established and coordinated use of shared standards and protocols is essential to aligning industry adoption of ZKP age verification. Given the emergence of ZKPs for age verification, there is currently no single uniform method of approaching implementation. Some standards bodies are working to address different components of this process. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C)’s models related to digital and verified credentials are being used to support Google and Apple’s digital wallet solutions, as well as Spain’s Cartera Digital beta initiative. Other organizations like the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) also develop standards relevant for age verification processes. Some jurisdictions, such as the EU, France, and Italy, have put forth technical standards to guide compliance with their legislation. It’s essential to build broad alignment on best practices and minimum requirements for privacy-preserving age verification because doing so will help reduce cost to implementers, ensure interoperability among different participants, promote healthy industry competition, and protect user privacy and security.

- Protect user privacy, security, and rights throughout implementations: While ZKP methods offer a greater level of privacy and security for age verification requests than current methods, they are still an emerging solution with many moving parts to figure out. The details of the implementation process are key to protecting personal data. While all entities involved may have a stake in maintaining user trust, and therefore data privacy and security, safeguards are still needed to prevent attempts to extract value from data. As such, it is important for both policymakers and industry players tasked with compliance to ensure users are protected throughout the age verification process. At the policy level, protections could include: ensuring compliance with existing data protection laws; requiring technical and legal independence between trust anchors, third-party facilitators, and websites requiring age verification; and implementing governance and accountability mechanisms that enforce data protections among all parties. At the technical level, developers should emphasize data minimization, selective disclosure of data, and unlinkability. This includes assessing and safeguarding against potential data attacks or opportunities for data misuse. Users should be protected from efforts that aim to identify existing information about them or link that existing information back to their age-verified activity. For example, measures should be taken to prevent tracking the frequency and cadence of age verification requests coming from a specific user, network, or device.

Our current digital ecosystem was not designed to enable age verification mandates. And as such, finding a privacy-preserving and user-protective method of age verification will require greater coordination and work from various stakeholders. These four considerations outline only some of the challenges and areas for collaborative problem-solving ahead. Other areas to consider include interoperability, management of compute power, and cost.

Four Recommendations for Industry and Policymakers

At their core, age verification mandates create greater restrictions on user access to online spaces. If U.S. lawmakers continue to push for these mandates, appropriate measures must be taken to ensure online age verification is implemented in a narrowly tailored, minimally restrictive manner, while also prioritizing user privacy and security. To achieve these goals, OTI provides these recommendations to policymakers and industry players tasked with compliance:

- As a matter of policy, age verification requirements should be narrowly tailored to limit burdens on freedom of expression and access to protected content. The recent U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling upheld the constitutionality of online age verification in the narrow context of accessing sexual content online. This ruling should not be interpreted as a blanket endorsement of the practice across the web. Age verification places burdens on users’ freedom of expression and poses risks to their online privacy and security, and as such its use across the web should be limited. As bills mandating the same requirements for social media or app stores continue to progress, litigation may force courts to further define the bounds of online age verification. Given the wider content restrictions these laws impose on all users, these bills can significantly impact everyone’s First Amendment rights and would thus have to meet the higher constitutional bar of strict scrutiny. On their end, policymakers should take action to narrowly tailor when age verification is acceptable.

- Wherever applied, technical solutions for age verification should use best-in-class privacy-preserving techniques. Protecting users’ sensitive, personal information and browsing data is critical to maintaining a free, open, and secure internet. Online age verification mandates should require any and all solutions to prioritize user privacy and security at the technical level. Currently, a promising method for doing so is through the use of zero-knowledge proofs, but privacy-preserving technologies are ever-evolving and require continuous study and evaluation. Measures should be taken to ensure protections are maintained throughout any implementations. Legislators should look to technologists, standard-setting bodies, and civil society for guidance on implementing best-in-class privacy-preserving techniques as they become available.

- When absolutely required, age verification mandates should be applied in the least restrictive and most tailored manner—at the service level. Age verification is most effective at the service level, where it would apply verification requirements solely to legally age-restricted content and the users seeking to access it. Websites and apps, which may host age-restricted content, are in the best position to determine when age verification is truly necessary. Age verification should not take place at the app store and device level because doing so subjects all users, regardless of the content they are trying to access, to unnecessary data-sharing requirements. At the same time, app-store-based verification is easily circumventable as users can simply choose to access content through the web rather than apps. Similarly, device or operating-system-level verification does not specifically target age-gated content and can open up users to more invasive views and control of their online and offline activities.

- Age verification solutions and implementations should prioritize user choice and data security. Users should be given a choice for how they can verify their age and with whom—including both the third-party facilitator and the established trust anchor providing proof of age. Offering different options allows users to choose entities they trust and can offer different avenues for complying with age verification mandates, particularly in circumstances where individuals lack access to formal ID. Enabling this range in choice will require establishing criteria and governing mechanisms for entities in the age verification process. To enable verifiable consent, clear, accurate, and easily accessible disclosure notices should be available for each verification method. Additionally, any method people choose to verify their age—whether with a government ID, biometric data, or using other personal identifiers—should have enforceable measures in place to protect against inappropriate data access, sharing, storage, and retention.

These four considerations and recommendations offer industry and policymakers a path toward exploring privacy-preserving age verification through the use of zero-knowledge proofs. Ongoing efforts to expand online age checks highlight the urgent need to create a feasible method for companies to meet requirements, while also protecting users. At the same time, policymakers will need to establish safeguards that combat misuse and widening applications of age verification. Ultimately, stakeholders will need to work together to build the necessary digital ecosystem to advance privacy-preserving solutions and protect the web’s legacy of free and open use.