Can Private Finance Save the World's Forests and Oceans?

Key Lessons From the 2021 Debt-for-Nature Swap in Belize

Blog Post

Shutterstock

Sept. 18, 2025

This article is part of the Power Switch series, which explores the need for systemic changes to critical minerals production, geopolitics, and climate finance to empower the Global South in the clean energy transition.

At a Glance:

- As development banks and donor countries fail to provide consistent public financing for sovereign debt and environmental challenges, debtor nations are increasingly turning to private sector solutions like debt-for-nature swaps, instruments that multilateral assemblies such as the Group of 20 (G20) and United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) are now seeking to scale up.

- A recent debt-for-nature swap in Belize employed an innovative private sector-led approach that refinanced a larger proportion of sovereign debt, utilized public funding more efficiently through credit enhancements, and generated larger conservation investments than previous government-to-government swaps.

- Despite this progress, the blended-finance approach has not fully addressed key shortcomings of earlier debt-for-nature swaps, such as small debt reduction relative to high transaction costs, risks to debtor country credit ratings, inadequate conservation metrics, and sovereignty and transparency concerns.

- To scale debt-for-nature swaps and related financial instruments, the G20 and COP30 must expand opportunities for credit enhancement, reform sovereign credit rating systems, employ conservation performance metrics, and improve stakeholder participation.

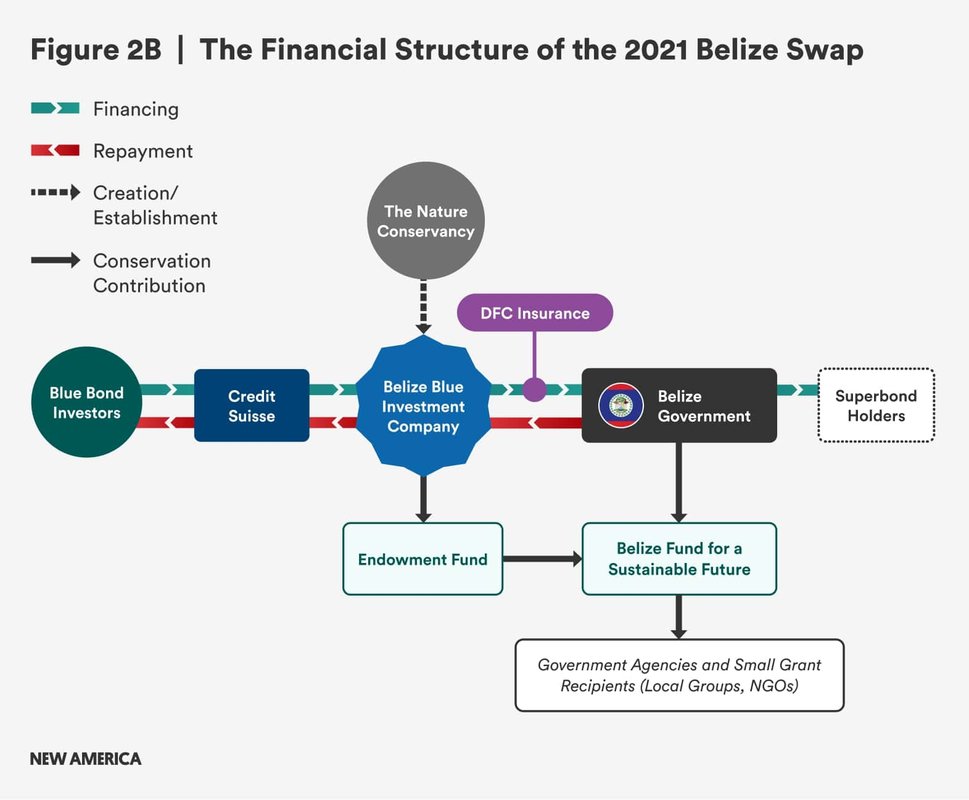

In 2021, the government of Belize was at risk of defaulting on hundreds of millions of dollars in national debt. But in November of that year, the small Central American country known for its Caribbean beaches and tropical rainforests executed the first of a new generation of debt-for-nature swaps characterized by a complex, blended-finance structure. The U.S. Development Finance Corporation provided $610 million in political risk insurance that enabled Belize to issue a $364 million Blue Bond, attracting new private investment to restructure much of its sovereign debt on more favorable terms. The financial close was announced on the sidelines of the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, with David Marchick, the Development Finance Corporation’s chief operating officer at the time, calling the collaboration with The Nature Conservancy, the Government of Belize, and Credit Suisse “one of the most innovative examples of climate finance and a model for the future.” With the resulting savings, Belize committed to redirect tens of millions of dollars in local currency toward long-term conservation goals, fishery and marine park management, and a range of NGO- and community-led projects.

Through its innovative blended-finance approach, the 2021 Belizean swap resulted in sizable financial and conservation impacts that substantially improved on a bilateral debt-for-nature swap in Belize two decades earlier. This brief outlines key areas of progress and ongoing challenges.

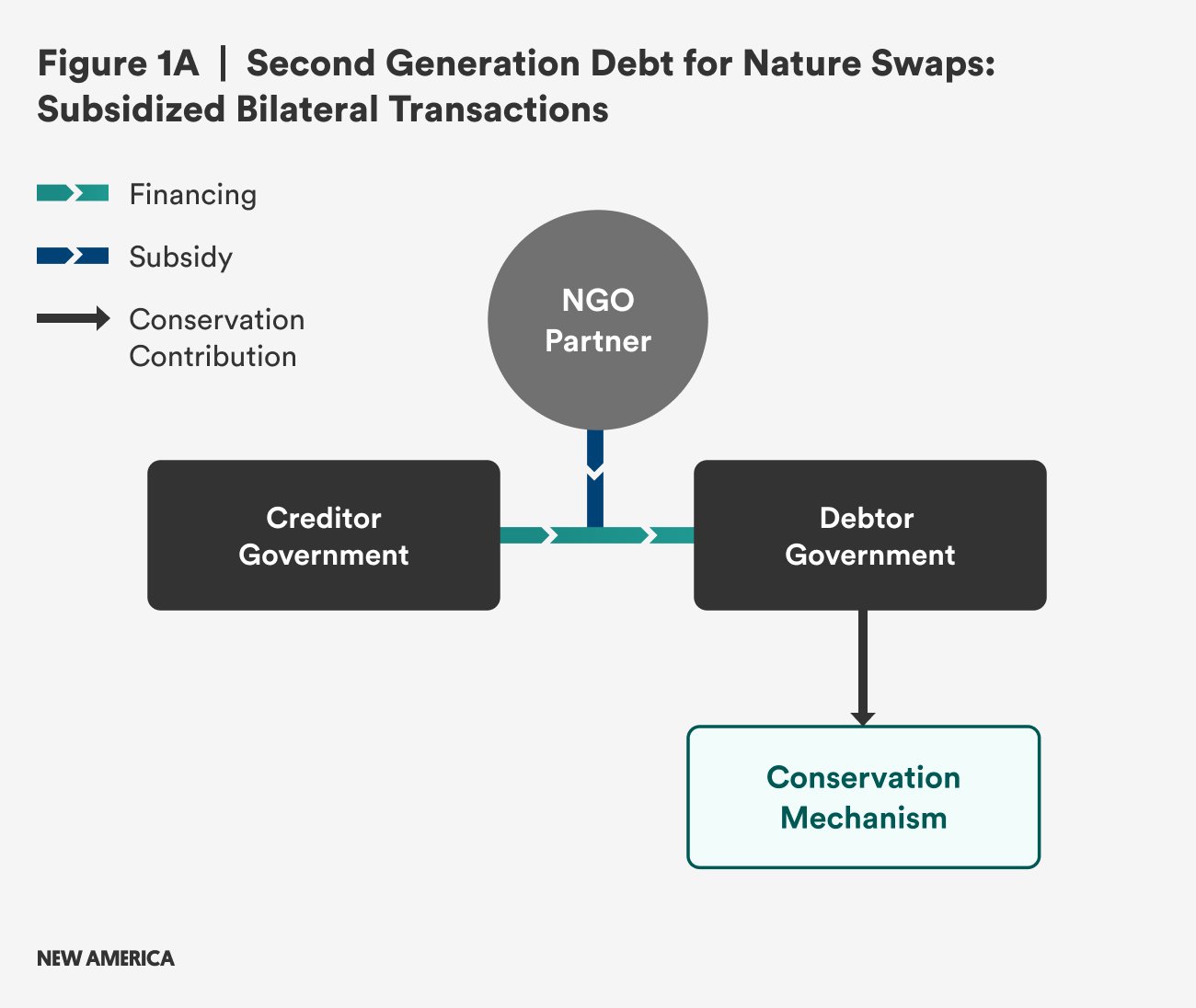

The Evolution of Debt-for-Nature Swaps

The idea of debt-for-nature swaps emerged in 1984 as a way to reduce the debt burden of low-income countries in exchange for environmental commitments; it became a reality when Conservation International executed the first swap in Bolivia in 1987. The concept capitalized on a mutual need: Debt-strapped countries rich in natural resources could reduce their financial burdens and wealthy creditors could achieve conservation goals. Early swaps involved international conservation NGOs working directly with debtor governments. In the 1990s, a second generation of deals involved government-to-government refinancing of concessional loans.

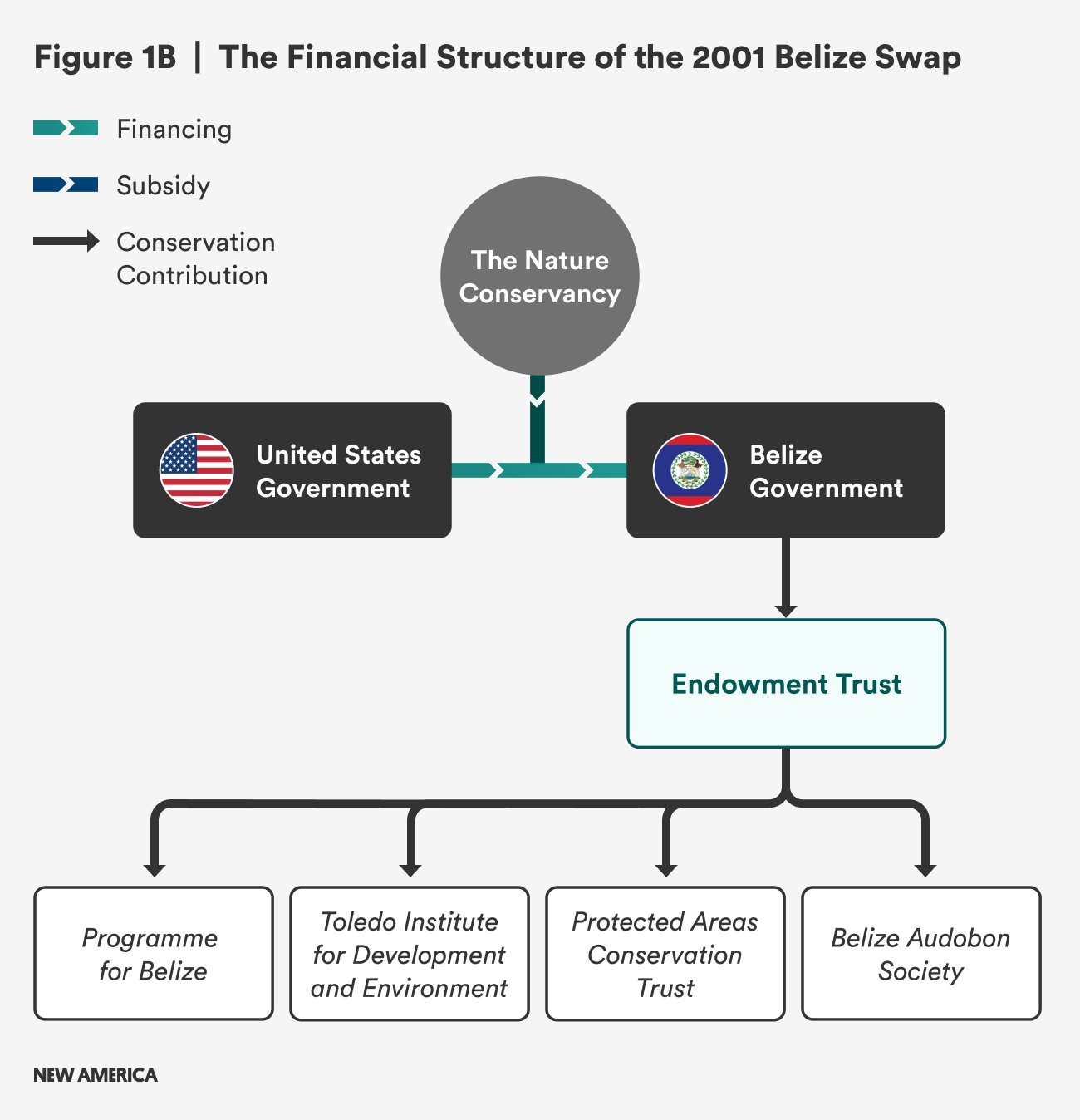

Belize’s 2001 Maya Mountain Marine Corridor Agreement

In 2001, Belize conducted a swap that was typical of second-generation bilateral deals: The U.S. government contributed $5.5 million, complemented by a subsidy of over $1 million from The Nature Conservancy (TNC), to retire roughly $8 million in U.S. loans to Belize. In exchange, Belize committed to protect approximately 23,000 acres of vulnerable rainforest and established a $7 million local-currency trust fund to support the work of four local NGOs to manage the country’s protected areas.

Source: Elizabeth Losos, New America/Alex Briñas

Source: Elizabeth Losos, New America/Alex Briñas

These early swaps faced a range of challenges. Finance ministers were reluctant to engage in complex negotiations, given that the amount of debt relief was small while transaction costs were high. Many also feared that simply engaging in debt relief discussions could harm their national credit ratings. Sovereignty and equity concerns were also a significant hurdle for debtor nations. In some places, potential swaps sparked local protests against perceived foreign appropriation of national resources. In 2003, Thailand annulled a bilateral agreement with the U.S. following false media reports that the deal would give the U.S. government control over Thai forests.

Meanwhile, inadequate environmental performance metrics and monitoring meant that the conservation impacts of many swaps conducted in the 1980s and 90s were dubious or unknown, leading creditors to question the benefits. Without proper monitoring, it is difficult to assess whether Costa Rica’s 1988 swap, for example, successfully protected a newly established park, given the increase in illegal gold mining and timber harvesting there following the agreement. In part because of these limitations, debt-for-nature swaps tapered off beginning in 2000.

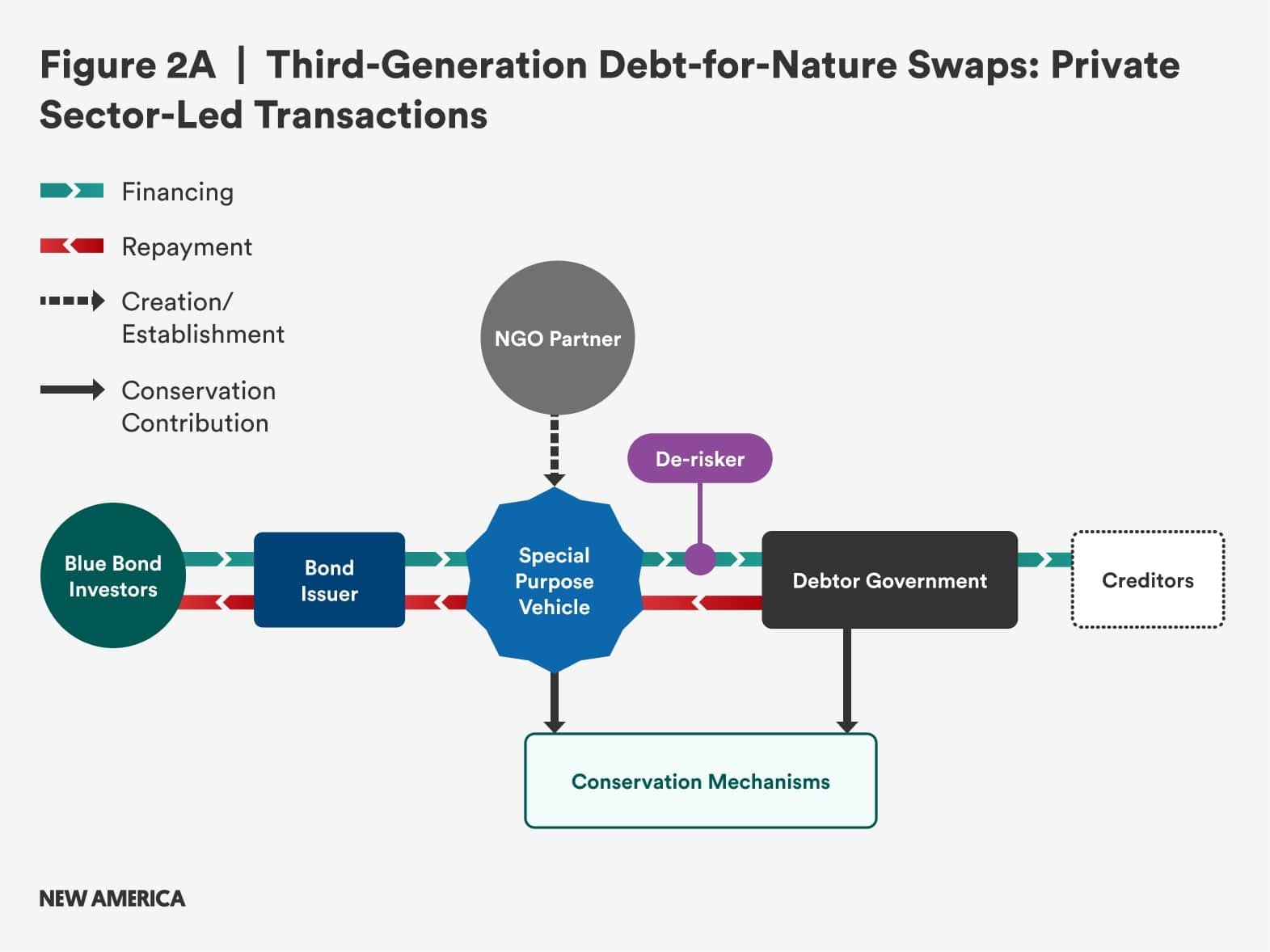

In the 2020s, as pandemic borrowing and inflation dramatically heightened debt distress, countries found they had few good options. Traditional debt restructuring was slow and limited, while new borrowing was increasingly expensive. At the same time, private investors were eager to fund projects with clear environmental benefits. These conditions created renewed interest in debt-for-nature swaps, this time involving private loan refinancing through green or blue bonds with public sector support in the form of credit enhancements. This new generation of private sector-led swaps has resulted in the restructuring of almost $6 billion in loans and generated nearly $2 billion in conservation financing in Seychelles, Barbados, Ecuador, Gabon, the Bahamas, and El Salvador.

Belize’s Groundbreaking 2021 Swap

By late 2020, Belize had undergone four recent defaults, and its sovereign foreign debt had ballooned above 125 percent of its GDP, almost twice the International Monetary Fund threshold for a sustainable debt load. The three major U.S.-based credit rating agencies all listed Belize’s sovereign credit rating as perilously close to default and its $553 million consolidated debt, known as a “superbond,” was selling at a steep discount on the secondary market. The country desperately needed a way to reduce its onerous debt-service payments. After 10 years of negotiations driven by TNC, Belize settled on a private sector-led swap.

Unlike its earlier bilateral debt-for-nature swap in 2001, Belize’s 2021 deal required a much wider range of public and private sector partners. TNC set up a special purpose vehicle, the Belize Blue Investment Company (BBIC), that helped Belize buy back its entire superbond at 55 cents on the dollar, reducing its debt from $553 to $364 million. BBIC raised money for this purchase through a new bond issued by Credit Suisse. The new bond had better financial terms than the original loan due to political risk insurance from the Development Finance Corporation. The refinancing meant that Belize now owed significantly less, with a better interest rate and longer payoff period. Belize will save an estimated $200 million in debt service reduction over the 20-year life of the new loan.

Because the deal reduced Belize’s debt-service burden, it led to some improvement in the country’s sovereign credit rating. It was not, however, an unambiguous win. While Standard and Poor raised Belize’s credit rating from “selective default” to B–, the other two primary ratings agencies did not register any impact from the transaction. Yet the silence from Fitch and Moody’s was still preferable to the downgrading many debtor nations fear: a classification of “distressed debt exchange” for daring to participate in debt swap negotiations.

On the conservation side, Belize established the independent Belize Fund for a Sustainable Future (BFSF), into which it deposited most of the swap’s debt-service savings—$4.2 million annually in Belizean currency for 20 years. BFSF distributes 40 percent of this revenue to government agencies that manage fisheries and marine parks and another 40 percent to in-country NGOs and community groups working on marine conservation through competitive grants. The remaining 20 percent supports BFSF’s administrative overhead. The government of Belize also set aside $24 million from the initial buyback savings to establish an endowment to support conservation work after the loan expires in 20 years. By then, the endowment is expected to reach $71 million, given annual contributions and estimated 7 percent annual market returns. Over its lifetime, the deal should generate an estimated $180 million in conservation funding.

As a condition of the agreement, Belize also committed to achieving its 30x30 international pledge under the Kunming–Montreal Biodiversity Framework, which calls for setting aside 30 percent of its ocean territory in marine protected zones. To reach the 30 percent target, the 2021 swap legally binds Belize to protect an additional 14.1 percent of its oceans by 2026 (given that it already had 15.9 percent under protection before the swap) and to develop a marine spatial plan to manage its entire marine economic exclusion zone.

Source: Elizabeth Losos, New America/Alex Briñas

Source: Elizabeth Losos, New America/Alex Briñas

Progress and Shortfalls

Financial Impact

Belize’s 2021 swap illustrates how this new, private sector-led approach can deliver substantially greater debt-service relief and mobilize significant new private capital compared with bilateral deals. It reduced Belize’s debt by 9 percent of its GDP—which, though modest, is notable—and revived its access to international financial markets. To date, it is the largest debt conversion relative to a country’s GDP of any debt-for-nature deal.

While these new swaps entail substantially higher debt reduction, their transaction costs have also ballooned with the addition of special purpose vehicles, multiple intermediary brokers, and insurance and re-insurance payments. The transaction costs of the 2021 Belize swap were estimated as high as $85 million. Critics argue that such outsized transaction costs are inefficient and lock up capital that could be deployed elsewhere.

Another significant feature of private sector-led swaps is their ability to attract new private financing using public sector credit enhancements, while bilateral swaps between creditor and debtor governments relied almost completely on direct public funding. In Belize’s 2001 swap, for example, the United States’s $5.5 million contribution from the Tropical Forest Conservation Act was supplemented by just over $1 million from TNC. By comparison, in the 2021 swap, the United States issued $610 million in political risk insurance via the Development Finance Corporation, which enhanced the creditworthiness of the newly issued private bonds, attracting $364 million in new investments to Belize. The U.S. would only make payments if Belize were to default, and that risk is partly offset by the annual insurance premiums Belize pays the U.S. government. Overall, this blended-finance structure appears to use public funds more efficiently.

Conservation Effectiveness

The 2021 Belize swap illustrates the growth in conservation scope of the new blended swaps compared with previous models. The more than $4 million per year in perpetuity that will be generated under the 2021 swap if the endowment fund performs as anticipated is roughly 10 times larger than the amount generated by Belize’s 2001 swap.

Geographical coverage has similarly expanded. While the 2001 Belize swap focused on one patch of rainforest within the Maya Mountain Marine Corridor, the 2021 deal evaluated the country’s entire ocean territory, identifying more than 14 percent for newly protected status. The national scale means that Belize’s marine conservation efforts are less likely to simply displace threats such as illegal fishing to a different location, thereby limiting persistent concerns about “leakage” that plagued prior swaps.

In another improvement, the 2021 swap identified conservation milestones and established penalties for noncompliance. An appendix to the agreement sets out a series of high-level benchmarks to measure progress toward the agreement’s goal of a healthy marine ecosystem and sustainable blue economy. Crucially, it requires the Belize National Assembly to authorize pre-determined increases in the country’s Marine Protected Areas by specific dates. If the legislature fails to meet those targets, Belize incurs a financial penalty.

While the inclusion of legally enforceable performance indicators is laudable, the choice of process metrics, such as legislative establishment of protected areas, over outcome metrics, such as evidence of a healthy marine ecosystem and commercially sustainable fish stock, can contribute to misleading results. There is a long history of “paper parks” that are authorized but not executed. More credible outcome indicators may be developed as part of Belize’s Marine Spatial Plan, which is required to implement the swap, but outcome metrics and monitoring are not required nor are there penalties for non-compliance.

Sovereignty and Transparency

While sovereignty infringement remains a key issue in the new generation of swaps, the national scope of the private sector-led deals has helped counter accusations that national sovereignty is being infringed. Earlier swaps typically focused on one or a few specific areas or projects, making them vulnerable to criticism that they prioritized the agendas of international conservation NGOs or foreign governments over those of debtor nations. In contrast, the 2021 Belize swap aligned with the government’s existing commitments to international biodiversity and climate agreements, which may have helped ease sovereignty concerns.

Belize’s established relationship with its NGO partner, TNC, may also have helped. TNC had a long-term presence in Belize, including a country office, and took part in negotiating Belize’s 2001 swap, which supported four local NGOs. That relationship set the stage for the decade-long negotiations that culminated in the 2021 deal.

Yet the complexity of private sector-led swaps can also strain relations with local communities. The special purpose vehicle and the many brokers introduce additional layers of bureaucracy and opacity that can expand the distance between decision-makers and the public. Some degree of secrecy is built into private sector-led swaps because, to take advantage of the discrepancy between the face value and secondary market value of distressed debt, negotiations must remain out of the public eye. Consequently, affected local communities are afforded minimal opportunities for input before financial deals close.

The 2021 Belize swap sought to address this lack of local consultation by mandating participatory meetings during the development of the Marine Spatial Plan. While 60 sessions were held with various stakeholders, it is unclear whether they materially affected the ultimate plan. Some community members charged that meeting notices were not broadly communicated and that the process was rushed, with pre-determined outcomes. Others complained that the distribution of grant funding has disfavored local NGOs with fewer connections and resources. Greater attention to local rights and representation before such deals close could improve transparency and address power imbalances.

A Path to Less Debt, More Nature

The upcoming G20 Summit in South Africa and COP30 in Brazil are poised to consider how to mainstream and scale private sector-led debt-for-nature swaps. To succeed, these bodies should address four critical issues.

Financial institutions, creditor and debtor governments, and impacted communities need relevant, outcome-based metrics to evaluate the conservation impacts of debt for nature swaps. Multilateral organizations should lead the way in creating a set of simple standards and tools to provide performance-based conservation metrics aligned with national and local priorities.

Stakeholder mapping, impact assessments, and consultation with local groups should begin at the earliest stages of the process, when key decisions are often made on governance and cost and benefit distribution. To achieve this, multilateral bodies can play a pivotal role in promoting a rights-based approach that is inclusive, equitable, evidence based, and transparent, and that occurs throughout the negotiation and implementation stages of future deals.

Given the importance of credit enhancement instruments such as insurance and loan guarantees for attracting hundreds of millions in new private finance, international bodies should create a public–private facility designed specifically to provide loan guarantees and risk insurance to support debt-for-nature swaps. While most credit enhancement instruments have been issued by public entities, scarce public funding has opened opportunities for philanthropies, nonprofit organizations, and the private sector to participate and even take leadership roles.

Finally, debt-for-nature swaps and related financial instruments will not scale without more clarity and consistency on how these deals could affect sovereign credit ratings. While private companies set ratings standards, multilateral development banks should press for guidance and standards that incorporate biodiversity and physical climate risk reduction into sovereign credit ratings.

Acknowledgements: Elizabeth Kroger, Meredith Langmuir, Nicholas Davalos, Enqi Zhou, and Otto Velting contributed to the development of this article.