Building Tools at the Boundary of Climate Science, Security, and Action

Phase Zero Webinar

Blog Post

Tim Roberts Photography/ Shutterstock.com

Nov. 26, 2018

The risk factors for social unrest, forced migration and conflict are shifting. The reasons why are not simple, and include complex interactions between demographics, rising standards of living, climate change, new technologies, and evolving demands on natural resources. Digital tools, especially interactive decision support models and data visualizations, hold great promise for helping governments, NGOs, businesses, and other organizations better understand, anticipate, and plan for today’s dynamic human security environment.

On September 25th, 2018, Denice Ross, the Data Strategy Lead for the Phase Zero Project at New America, co-hosted a Webinar on “Building Tools at the Boundary of Climate Science, Security, and Action,” with Professor Dave D. White from the School of Community Resources & Development at Arizona State University, who also directs the Decision Center for a Desert City. Ross and White shared insights from careers dedicated to building organizations and digital tools that bridge data and action, with Ross coming from the perspective of government and NGOs, and White from academic research.

Survey of the field of tools spanning boundary of science and action

Ross’ presentation explored why attempts to span the boundary between data science and public policy practice have failed to spur action, particularly in the field of climate security. According to the literature on "boundary objects," or analytical tools that seek to span that boundary between research and practice, in order for decision tools to be effective they must be credible, salient, and legitimate. Credibility covers the validity and technical accuracy of the analysis. Salience refers to how relevant the information is to the decision-makers’ needs, and legitimacy requires that the information is cognizant of the stakeholders’ values and beliefs.

At the 2017 Planetary Security Conference, an international climate change conference funded by the Government of The Netherlands, Ross found through proxy interviews with national security practitioners that there was a need for tools that make the science digestible, relevant, and actionable. This spurred Phase Zero’s Landscape Survey, which examined tools within the climate change, natural resource, and security space. The Landscape Survey assessed more than sixty tools and interviewed more than two dozen tool-makers and thirty climate security experts to identify the barriers for tool uptake.

The key barriers to turning data into action are understandable, given the relative nascency of the field. The barriers fall into two main categories:

- Most tools are built for raising awareness, not informing action (as one would expect in a field that is just beginning to mature), and focus on the risks, rather than on possible solutions.

- Due to the complexity of the domain, most tool development processes are focused on tech and data, not users and the decisions they need to make.

However, there are a few decision tools that have made the leap from data to action and can be instructive.

Global Forest Watch is an online platform that provides data and tools for monitoring deforestation. On the website, users can customize alerts so that they are highly relevant to the geographic areas a user is interested in.

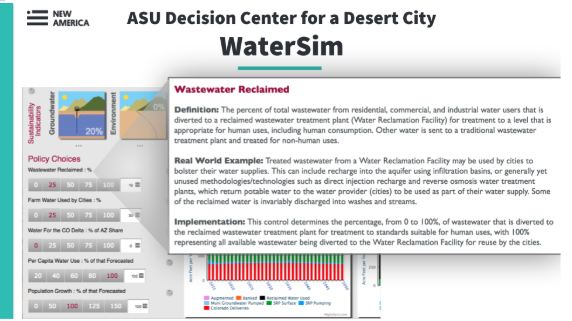

ASU Decision Center for a Desert City’s WaterSim is a model-based decision support tool for water resources, with a bank of 72 water policy choices.

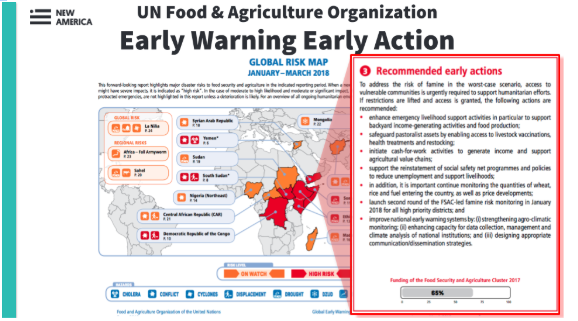

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations’ Early Warning Early Action tool forecasts new emergencies or the deterioration of existing conditions quarterly and recommends early actions to address the forecasted risk.

As data and technology mature, tool developers are shifting from a technology-centered to a user-centered approach, designing tools for the tasks users need to accomplish and the decisions they need to make. This often manifests in a more focused target audience, for example, rather than a general audience of policymakers. A tool, for example, might be custom-built for sustainability directors in city governments.

Three tools that focus on building utility with, not just for, the user involve methodologies that increase the likelihood the tool will be both salient and legitimate. One takeaway from these tools is to aim for an "80% solution" data platform. Rather than delivering a totally finished data platform, technologists can work directly with stakeholders to customize the functionality of the tool through the procurement of local or proprietary data sources to meet their particular decision-making requirements.

- Earth Genome’s Green Infrastructure Support Tool (GIST) worked with 7 companies that are members of the World Business Council for Sustainable Development in order to identify options for corporate decisions on water use.

- IASC/European Commission’s Index for Risk Management (INFORM) is primarily a country-level risk index tool, but it includes subnational data products, as well. INFORM effectively downscales by engaging national and subnational stakeholders to ensure the work is locally owned and managed, increasing the salience of the product.

- MapX, developed by the United Nations Environment Program, the World Bank, and the Global Resource Information Database, has a formalized process for engaging with end users to create a tool that is salient and legitimate.

In sum, from her research on tools spanning the boundary of climate science and action, Ross recommends tool developers do the following:

- Design beyond the problem to include the solutions;

- Build with, not for, end users; and

- Launch tools into existing networks and decision making processes.

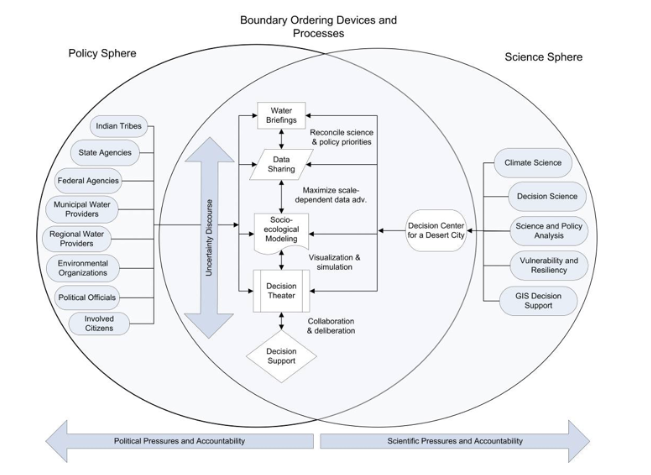

Applied academic view of boundary organization and objects

White’s presentation focused on his first-hand knowledge of building boundary organizations (i.e., organizations that attempt to bridge the gap between science and practice) as the Director for the Decision Center for a Desert City (DCDC). White discussed how the standard linear model of science-policy interactions is not only “inaccurate but also ineffective in addressing complex environmental problems.” White emphasized that environmental decision making requires linking multiple viewpoints between individuals and institutional actors spanning both science and policy. In order to co-produce knowledge and policy effectively, a recursive and iterative process is required between stakeholders and product developers.

Model-based decision-support tools are one type of boundary object. These are scenario-driven analytic tools, populated with specific data, meant to support a specific decision making process. They are inherently at the intersection between science and policy. As a result, expert stakeholders have to work together to reconcile their often divergent priorities when it comes to environmental concerns and risk perceptions in order to get the model right. White discussed which techniques are most conducive for eliciting feedback from diverse stakeholders on these sensitive topics and found that stakeholders collaborate best when there is a clear problem-solving focus.

To create the WaterSim decision support tool, which estimates the water supply and demand for the Phoenix metropolitan area, the DCDC held a series of stakeholder meetings, bringing together the science and policy communities. White referenced Crona and Parker’s research, which found that policymakers who were socially connected to DCDC researchers were more likely to utilize the WaterSim tool to help them make decisions about investments or water management. Similar to the GIST, INFORM, and MapX platforms described by Ross, DCDC’s suite of tools maintain the same robust scientific research on the back-end (i.e. all the data and science that is not visible to the end-user) and have the capability to adapt the user interface for different audiences.

By using an interactive, evidence-based approach to building a boundary organization in DCDC, the ASU team is seeing real-world outcomes:

- The DCDC is viewed as an “honest broker” by community and local government stakeholders because it serves as a clearinghouse for data and a hub for forging connections between subject matter experts in the university and decision-makers.

- The co-production of the decision support system ensures that the outputs are germane to decision makers when it comes to city planning, policies, and infrastructure financing.

Concluding thoughts

Ross and White both spoke to the advantages of building a core platform that is flexible enough to be constantly adapted and updated. They concluded that developing effective tools requires circular rather than linear development methodologies and that it is never too early to engage with users.